A Mighty Fortress Is Our God

Martin Luther, 1529; translated by Frederick H. Hedge, 1853

Addressed to one another

| A mighty fortress is our God, | Ps. 46:1, 7 |

| a bulwark never failing; | |

| our helper he amid the flood | Ps. 32:6; 46:3; 69:14; 124:4; Rev. 12:15–16 |

| of mortal ills prevailing. | |

| For still our ancient foe | John 8:44; Rev. 12:9 |

| doth seek to work us woe; | 1 Pet. 5:8; Rev. 12:12, 17 |

| his craft and pow’r are great; | Dan. 8:24–25 |

| and armed with cruel hate, | |

| on earth is not his equal. | 1 John 5:19 |

| Did we in our own strength confide, | Eph. 2:9; Phil. 3:3 |

| our striving would be losing; | Ps. 146:3 |

| were not the right man on our side, | 1 John 5:18 |

| the man of God’s own choosing. | |

| Dost ask who that may be? | Ps. 24:10 |

| Christ Jesus, it is he, | |

| Lord Sabaoth his name, | |

| from age to age the same, | |

| and he must win the battle. | Col. 2:15 |

| And though this world, with devils filled, | |

| should threaten to undo us, | |

| we will not fear, for God hath willed | Neh. 4:14 |

| his truth to triumph through us. | |

| The prince of darkness grim, | Eph. 6:12 |

| we tremble not for him; | |

| his rage we can endure, | Eph. 6:16 |

| for lo! his doom is sure; | John 16:11; Rev. 20:10 |

| one little word shall fell him. | Rev. 12:11 |

| That Word above all earthly pow’rs, | John 14:30 |

| no thanks to them, abideth; | |

| the Spirit and the gifts are ours | Eph. 1:3–14 |

| through him who with us sideth. | |

| Let goods and kindred go, | Matt. 19:29; Luke 12:33 |

| this mortal life also; | Matt. 16:25 |

| the body they may kill: | Matt. 10:28 |

| God’s truth abideth still; | 2 John 1:2 |

| his kingdom is forever. | Ps. 45:6 |

The alphabetical ordering of hymn studies on this website allows us to begin where it all started: with Martin Luther—the first great composer of congregational songs—and with his most beloved poem and his most beloved tune. Whatever else one might think about this song, it must be admitted that the practice of congregational singing began powerfully, with bold imagery—and with a rhythm and sense that can jolt complacent singers. Those who bathe in these headwaters find them bracing. No hymn subsequently written has treated the realities of spiritual warfare more unabashedly or more honestly.

It must also be admitted, however, that Frederick Hedge’s English syntax (at least in the first two stanzas) threatens to buckle under the pressures of translation. In any lesser hymn, a clause as convoluted as “our helper he amid the flood of mortal ills prevailing” (meaning, “he is our helper, prevailing amid the flood of mortal ills”) would disqualify it from the congregation’s repertoire. As it is, the strengths of this song compensate for its infelicities, of which everybody can make good sense with just a little help from the pulpit. Then, in stanzas three and four, the syntax straightens out to parallel nicely the poem’s progression of thought from adversity to victory.

All hymns make congregants say things, the truth of which they may or may not in the moment feel existentially. So, too, here. Everybody, from the most self-assured Pharisee to the most doubtful backslider, begins by professing that God is a mighty fortress. The next stanza and a half prove that we need a fortress, because we are assailed by an extraordinary foe. There is no one on earth like him, and if we try to defend ourselves merely with our own strength, he will vanquish us. Thus the stage is set, midway through stanza 2, for the arrival of a savior, “the man of God’s own choosing,” who will win for us access to the fortress. It is only natural that those who hear our song wonder, like characters in a chivalric romance (such as Ivanhoe or Lohengrin), at the identity of the champion, in echoes of Psalm 24.

Only with the gravity of the conflict and the real nature of the combatants thus defined, can we sing stanza 3 with the confidence called for by the text. We endure the rage of the prince of darkness by fixing our attention on the promise that “his doom is sure.” Subsequent lines even turn ironic in triumph. Everybody has heard that “sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me,” but not so for Satan—as Luther turns the figure of speech at the end of stanza 3 into a pun on John 1. Finally, stanza 4 in lines 5–7 asserts something which may appear superficially to contradict the thesis of the hymn but which, in fact, decisively clarifies it. If God supposedly prevails against our mortal ills, why are we at this point talking about the loss of property, loved ones, and even “this mortal life”? Because the eternal life we enjoy now in Christ, though enriched by these things, depends not on them but on the Spirit and gifts of him whose kingdom is forever.

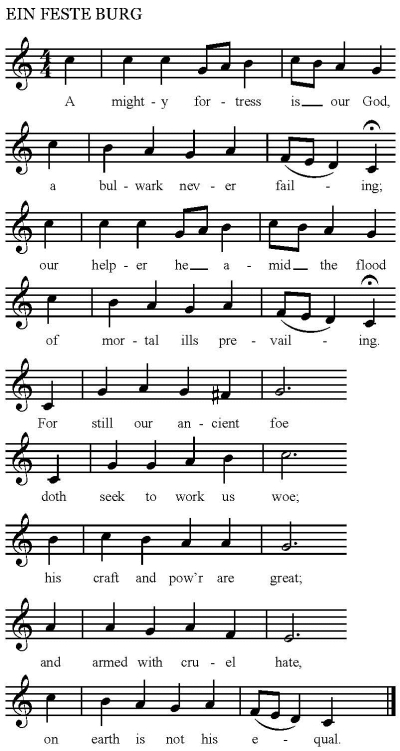

Musically, the might of the fortress and impregnability of the bulwark is matched in Luther’s tune to the irrefutable logic of a descending C-major scale. Line 1 falls by leap from high “do” (C) to “sol” (G) and finds that it must pause, or cadence, there. Line 2 starts all over again from the beginning but, this time, descending by step, manages to push past “sol” to span the octave from high “do” down to low “do.” Lines 3 and 4, being set to the same melody as lines 1 and 2, review the premises of the argument (so to speak) that any descent from “do” must come to terms with “sol” as a secondary center of gravity. Then, in line 5, where the pulse of the poem quickens to shorter lines of six syllables each (instead of seven or eight) that rhyme in couplets (instead of the interlocking rhymes of the opening quatrain), and where stanza 1 introduces “our ancient foe,” the melody reverses direction and ascends by leap from low “do” (C) to “sol” (G). Line 6 pushes past “sol” to climb the scale to high “do” (just as in lines 2 and 4, but in the opposite direction). Hence we find ourselves back on the pitch where we began, but with a perspective that enables us to expand the subsequent return to low “do” into three lines of measured descent. Line 7 descends stepwise from high “do” to “sol.” Line 8 descends from “la” to “mi,” generating in this way a peculiar harmony that colors the uncanny facts of Satan’s “cruel hate” and “doom” in stanzas 1 and 3, as well as the fact of God’s immutability in stanzas 2 and 4. Finally, the last line calmly returns to the opening seven-syllable rhythm (even as its text stands apart from the rest of the stanza by not rhyming), when the melody of lines 2 and 4 returns in a complete descending C-major scale that summarizes the course of the whole tune.