Alas! and Did My Savior Bleed

Godly sorrow arising from the sufferings of Christ

Isaac Watts, 1707

Addressed to ourselves (and one another?), then to God

| Alas! and did my Savior bleed, | Rom. 5:9 |

| and did my Sovereign die! | John 19:15 |

| Would he devote that sacred head | Is. 50:6 |

| for such a worm as I! | Is. 41:14 |

| Was it for crimes that I had done | Is. 53:5 |

| he groaned upon the tree! | Matt. 27:46 |

| Amazing pity! Grace unknown! | 1 Pet. 1:10–12 |

| And love beyond degree! | |

| Well might the sun in darkness hide, | Is. 13:10; Joel 2:10; Matt. 27:45 |

| and shut his glories in, | |

| when Christ the mighty Maker died | Phil. 2:5–8 |

| for man the creature’s sin. | |

| Thus might I hide my blushing face | |

| while his dear cross appears; | |

| dissolve my heart in thankfulness, | Luke 7:38 |

| and melt mine eyes in tears. | |

| But drops of grief can ne’er repay | |

| the debt of love I owe; | |

| here, Lord, I give myself away, | Rom. 6:13; 12:1; Phil. 3:7 |

| ’tis all that I can do. |

Every honest Christian is tempted to treat lightly the work of the Cross. Living with the imputed righteousness of Christ upon us, we are tempted to forget how great the work was which brought about this imputation. Part of the reason we are drawn to this temptation is the sheer difficulty in reflecting on the vast work of the cross. Here, Isaac Watts admits the difficult work of contemplating the cross and yet endeavours it. Giving voice to our thoughts, he begins with the question which faces all Christians and to which all Christians must answer in the affirmative.

Watts devotes the first two stanzas to this question—did the God of all creation die to redeem me? The first two stanzas work as a unit and present the question (and its obvious answer) as a bittersweet one. Rightly, the hymn begins with “alas,” since we first see only the tragedy of the cross, but the second stanza affirms this work as “Amazing pity! Grace unknown! And love beyond degree!” This set of declamations shows that the sorrow of the hymn’s opening word is really also a joy.

The third and fourth stanzas also work as a unit, which begins with a poetic conceit about the darkness at Christ’s death. The personification of the sun here, who wilfully hides his face from view, is not without biblical warrant. We learn in Psalm 19 of how this same sun declares the glory of God. How could the sun then look upon Christ’s estate of humiliation without hiding his face? The imagery becomes more useful as the third stanza progresses. It is for the “creature’s sin” that Christ dies. The sun, a fellow creature, has not sinned; indeed he has only shown forth God’s glory since the beginning of creation. But man, the “worm” of the first verse, has sinned so much that the very source of the sun’s glory must humiliate Himself, taking on the cursed death of the cross. What was a conceit in the third stanza becomes a model in the fourth as we follow the sun’s example and hide our faces, which blush to match the color of the sun. Then the liquid imagery of the next several lines harks back to something even earlier in the poem—its opening image—but there can be no comparison between the flow of the Savior’s blood and that of our own drops of grief.

Admitting the magnitude of the cross is never enough, and Watts does not stop there. He moves on to summarize the devotion that is required of those who would partake of the benefits of the cross. He sums it up simply as giving one’s self away.

With a name like MARTYRDOM, it’s not surprising that the tune most often used for “Alas! and Did My Savior Bleed” has always been associated with texts that improbably combine sadness, longing, and hope—such as psalms 42 and 130. The version of the tune in use today, and especially its accompanying harmonization, is helpful in expressing that nearly ineffable concept Watts turned his pen to. The non-chord tones in the harmony are carefully placed to accentuate important moments in the text.

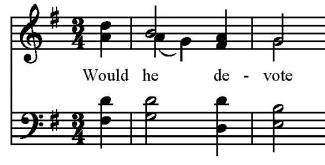

For example, in the eighth full measure, which is the first full measure of the tune’s second phrase, the alto is given an unusual non-chord tone:

We expect a very satisfying arrival on a G chord (in the first stanza, on the word, “he”) but the alto voice frustrates it by lingering too long on the previous note and resolves too late. Like Watts’s text, the tune focuses on the bittersweet nature of the cross. This example shows us the bitter, but what of the sweet? It comes in the closing gesture. The tune has an incredibly persistent rhythmical pattern of a quarter note followed by a half note. This pattern dominates nearly the entire tune. The major exception is the tune’s closing idea where the melody moves exceptionally on the second beat of the measure:

After the largest leap in the entire melody, and a descending one too, we quickly climb back up and finish with a satisfying cadence. The persistent rhythm sung earlier in the tune is abandoned so that the melody can ascend again. In this text-tune combination we find a perfect marriage of bitterness and sweetness. This does not fully explain the miracle of the cross, but we think Watts understood that this may be as close as one can come in this life.