All Praise to God, Who Reigns Above

J. J. Schütz, 1675; trans. C. Winkworth, 1858, and F. E. Cox, 1864

Based on Deuteronomy 32

Addressed to one another

| All praise to God, who reigns above, | Ps. 123:1 |

| the God of all creation, | |

| the God of wonders, pow’r, and love, | |

| the God of our salvation! | |

| With healing balm my soul he fills, | |

| the God who every sorrow stills. | 2 Cor. 1:4 |

| To God all praise and glory! | Deut. 32:3b; Ps. 98:4; Rom. 11:36 |

| What God’s almighty pow’r hath made | |

| his gracious mercy keepeth; | Ps. 121:3–6 |

| by morning dawn or evening shade | |

| his watchful eye ne’er sleepeth; | 1 Kin. 18:27 |

| within the kingdom of his might, | |

| lo, all is just and all is right. | Deut. 32:4 |

| To God all praise and glory! | |

| I cried to him in time of need: | Ps. 34:4 |

| Lord God, oh, hear my calling! | |

| For death he gave me life indeed | Ps. 56:13; Eph. 2:5 |

| and kept my feet from falling. | |

| For this my thanks shall endless be; | |

| oh, thank him, thank our God with me. | Ps. 34:3 |

| To God all praise and glory! | |

| The Lord forsaketh not his flock, | John 10:12 |

| his chosen generation; | 1 Pet. 2:9 |

| he is their refuge and their rock, | Deut. 32:4, 15, 18, 30, 31, 37 |

| their peace and their salvation. | |

| As with a mother’s tender hand | Deut. 32:10–11, 13; Matt. 23:37 |

| he leads his own, his chosen band. | |

| To God all praise and glory! | |

| Ye who confess Christ’s holy name, | Deut. 32:3a; 2 Tim. 2:19 |

| to God give praise and glory! | |

| Ye who the Father’s pow’r proclaim, | |

| to God give praise and glory! | |

| All idols underfoot be trod, | Deut. 32:15–21, 37–38 |

| the Lord is God! The Lord is God! | Deut. 4:35; 1 Kin. 18:39 |

| To God all praise and glory! | |

| Then come before his presence now | Ps. 95:2 |

| and banish fear and sadness; | |

| to your Redeemer pay your vow | Ps. 61:8; 65:1 |

| and sing with joy and gladness: | |

| though great distress my soul befell, | |

| the Lord, my God, did all things well. | Mark 7:37 |

| To God all praise and glory! |

Shortly before Moses died, the Lord explained to him that the people of Israel, after enjoying the goodness of the land, would be inclined to turn to other gods, which in fact were no gods at all (Deut. 31:16–22). So rebellious is the human heart that even one who has known a time when “the LORD alone guided him,” when “no foreign god was with him” (Deut. 32:12), can nevertheless be tempted to find in created things an explanation of reality, a purpose in life, a balm to the soul, and an object to worship. What he really finds is confusion and disaster. Therefore God bid Moses teach the people the song recorded in Deuteronomy 32, which would warn them, and us, against this temptation.

The hymn at the head of this essay was written by a 17th-century German lawyer, Johann Jacob Schütz, not to paraphrase Moses’s song, but to respond to it. Modern Christians who sing it and mean it have essentially taken God’s warning to heart. They assert that all creation has a God, who, reigning above, must be distinguished from creation. And they exhort one another to give all their praise to him alone. Soli Deo Gloria. The refrain at the end of every stanza in the original German comes directly from Luther’s translation of Deuteronomy 32:3b: Gebt unserm Gott allein die Ehre, that is, “Give to our God alone the honor!”

The opening stanza anticipates the course of the entire hymn as it begins with an exhortation to praise, moves to an exposition of God’s deeds, and returns to an exhortation to praise. The first word, “all,” serves as a headmotif, developed not only in the refrain but throughout. In creation we see the manifestation of God’s all-mighty power (stanza 2, line 1). He keeps and governs that creation for the purposes of his sovereign rule, in which “all is just and all is right” (stanza 2, line 6). Indeed, with those who saw Jesus heal the deaf and mute man in the Decapolis, we declare that he “did all things well” (stanza 6, line 6, where the original German is even more insistent: Gott hat es alles wohl bedacht / und alles, alles recht gemacht). We would tread “all idols underfoot” (stanza 5, line 5), for greatness and salvation can be found only in our one God. In stanza 3, which leaves God’s decrees to describe my neediness, “all” appears only as a veiled phoneme, lost between initial consonants and a participial suffix in the feminine rhyme: calling/falling.

The poetry is beautiful. Its elegant and consistently iambic rhythms make the most of the stanza-structure, 8.7.8.7.88.7, which makes its “windup” in decisive lines of eight syllables alternating with gentler lines of seven, “releases” in a rhyming pair of eight-syllable lines, and “follows through” with the refrain. The rhymes are perfect and imaginative throughout, especially the two-syllable rhymes at the ends of lines 2 and 4. Every stanza has its felicitous details, such as the spondee in the initial foot of stanza 3, line 2:

/ /

Lord God, oh, hear my calling!

This, the only metrical hiccup in the whole poem, puts an edge on the singer’s recollection of the cry. More mellifluous is the alliteration in stanza 4, lines 1 and 3: forsaketh/flock and refuge/rock.

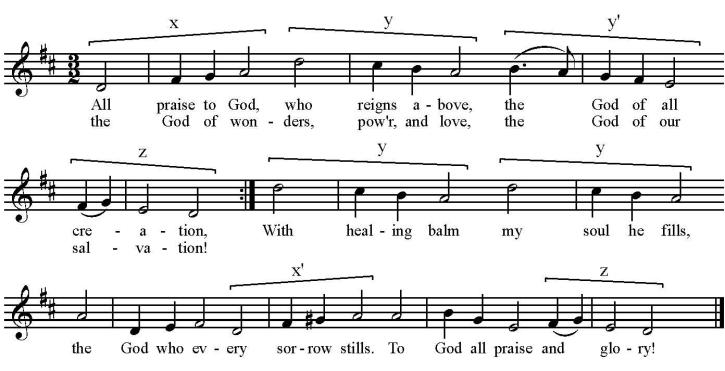

The tune MIT FREUDEN ZART unfolds as a memorable and meaningful progression of phrases. The progression is memorable because nearly every three-beat melodic unit in the song conforms to the same rhythmic pattern: long–SHORT–short–long. (The only melodic units that don’t are the feminine cadences at the ends of the seven-syllable lines, labeled “z” below). It is meaningful because the melodic units relate to one another and follow one another in ways that make musical sense. The first melodic unit (labelled “x” below) begins by emphasizing the headmotif, “all,” with a half note on the first scale-degree, then ascends through the third and fourth scale-degrees to reach the fifth. This assertive beginning precedes a leap up to high D, an octave above where we started. In a sense, the syncopated punch on the third beat of the first complete measure generates all the rhythmic life of the rest of the tune, in that every subsequent melodic unit reverberates from this leap. The second melodic unit (labelled “y” below) follows on from the first in what musicians call a “tonal inversion”: after x ascends from the first scale-degree to the fifth, y descends in identical rhythm from the upper first scale-degree down to the fifth. Then the third and fourth melodic units, y' and z, ensue as variants of the second melodic unit, in descending sequence. Thus the first part of the tune takes the congregation on what Paul Westermeyer calls “a wonderful ride over its arch”—a steeply ascending octave and a measured, even logical, descent via gentler arches to where we started. But the ride, more initially precipitous than even ANTIOCH, TRURO, or DUKE STREET, is not just for fun. It measures symbolically the distance between “above” and “creation.”

The tune builds momentum by repeating the first part, then releases the second part with back-to-back restatements of the high point of the ride, melodic unit y. These are answered by two ascending melodic units, the second of which mimics the opening melodic unit of the tune, chromatically altered (with the addition of the G-sharp) to assert even more aggressively the fifth scale-degree (x'). This transformation of x into x' not only makes the ensuing restatement of the feminine cadence (z) sound all the more conclusive, it also intensifies the reiteration of “the Lord is God!” in stanza 5. In this way we arrive with great musical conviction at the refrain of what surely is a fine response to Deuteronomy 32—“To God all praise and glory!”