All the Way My Savior Leads Me

Fanny J. Crosby, 1875

Addressed to one another

| All the way my Savior leads me; | Deut. 1:31; Josh. 24:17; Ps. 78:52–54 |

| what have I to ask beside? | |

| Can I doubt his tender mercy, | Luke 1:78–79 |

| who through life has been my guide? | |

| Heav’nly peace, divinest comfort, | Is. 26:3; Phil. 4:7; Matt 5:4 |

| here by faith in him to dwell; | |

| for I know whate’er befall me, | |

| Jesus doeth all things well. | Mark 7:37; Rom 8:28 |

| All the way my Savior leads me, | |

| cheers each winding path I tread, | |

| gives me grace for ev’ry trial, | 1 Cor. 10:13 |

| feeds me with the living bread. | John 6:35 |

| Though my weary steps may falter, | |

| and my soul athirst may be, | |

| gushing from the rock before me, | Ex. 17:6; 1 Cor. 10:4 |

| lo, a spring of joy I see! | Rev. 7:17 |

| All the way my Savior leads me— | |

| oh, the fullness of his love! | Eph. 3:19 |

| Perfect rest to me is promised | Matt. 11:28–29; Heb. 4:9 |

| in my Father’s house above: | John 14:2 |

| when my spirit, clothed, immortal, | 1 Cor. 15:53 |

| wings its flight to realms of day, | |

| this my song through endless ages: | |

| Jesus led me all the way! |

Many late nineteenth-century hymns consist of a single poetic idea which is expanded over several verses, and this one is no exception. Here Fanny Crosby discusses the continual guidance given to us by our Lord: his leading us along our way, his sharing our path with us, and his feeding us. This image is central in Scripture and appears as early as Genesis 12, when God leads Abram from the land of his fathers into a land which He would show him. But the image was perhaps especially familiar to Fanny Crosby. Blinded shortly after birth, she regularly needed the help of guides, upon whom she had to rely in an analogous way. We are as blind to the hidden providence of God as Crosby was to her own physical way, and therefore we need a guide who can see clearly what we cannot—one, moreover, whom we can trust has the best of intentions.

Crosby’s contentment with her blindness has been well-rehearsed elsewhere, and even in her own writings. It is no surprise that contentment then is the first theme of the hymn. With Christ as a guide, who could be discontent? Her question, “what have I to ask beside,” carries with it an implicit answer, but the hymn goes on to give reason why we should be content with Christ. His guidance in the past (line 4), the peace and comfort we have already received by faith, should assure us that, with Christ as our guide, we need not fear ever going astray (lines 7–8).

The second stanza focuses on the support that Christ gives along the way. The stanza moves seamlessly from Old to New Testament references, with Christ as the living bread, prefigured by manna in the wilderness, and Christ as a living stream, prefigured by the streams which came forth from the rock in Exodus 17. Thus Crosby turns our minds back to the journey of Israel, guided as it was by a cloud during the day and a fire during the night.

Having referenced the past in stanza 1 and the present in stanza 2, we sing about the future in stanza 3. He would be a bad guide indeed who led a blind person on without giving him some insight about where he was going. Crosby wisely finishes her hymn with a stanza which reminds us of our destination. Yet, even upon our arrival we will still speak of Christ as our guide.

Most of Fanny Crosby’s hymns were fortunate enough to have tunes designed especially for them. This fortune sometimes becomes a curse, for the late nineteenth century produced many transient and un-idiomatic hymn tunes, which were responsible in part for the decline in congregational singing throughout the twentieth century. In the case of this hymn, however, the text is presented with some success. One might even think of the hymn tune itself, metaphorically speaking, as a kind of guide, moving us along a journey of sorts from its musical home and then back again, providing a predictable rhythm while moving us along and then firmly establishing our place at our musical home, all the while giving voice to this text about Christ’s guidance.

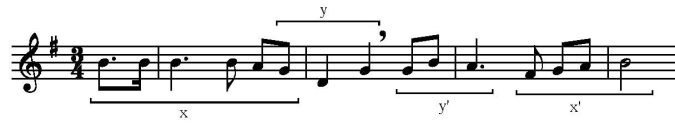

A single rhythmic pattern (with one slight variation) recurs in all the phrases of the tune: a two-note, one-beat pickup leads to a dotted quarter note on the downbeat, followed by three eighth notes and finally a cadence on the next downbeat. This idea repeats every two measures, making the rhythm predictable for the congregation, until after seven statements it is decisively altered in the penultimate measure (the dotted quarter being displaced by two eighths and a quarter at “doeth all”). Although the pitches sung to this rhythm are never the same twice, they follow one another in ways that suggest progress. For starters, the first two lines are something of a melodic palindrome: the rhythm described above is first set to a descending scalar figure (x) and a figure that leaps down and back again (y), then by a figure that leaps up and back again (y') and an ascending scalar figure (x').

The four main cadences at the ends of lines 2, 4, 6, and 8 relate nicely, with the first ending on the musical home base, but weakly (what music theorists call an imperfect cadence). This type of cadence offers some melodic conclusiveness but also raises melodic questions, which arrive here in the next four measures (at precisely the point, interestingly, where a verbal question is asked in Crosby’s first stanza). Line 4 ends on a sonority that is not the musical home base. Our departure to a new resting place is prefaced by notes outside the key (notice the C-sharps in the alto). Line 6 also ends at this same new resting place, though with less force (notice, in contrast with lines 3–4, the C-naturals in soprano, tenor and bass). Finally, Line 8 concludes with a cadence in the home key, which, unlike the first, is strong. To add a degree of security to the hymn’s conclusion, this last phrase is repeated.

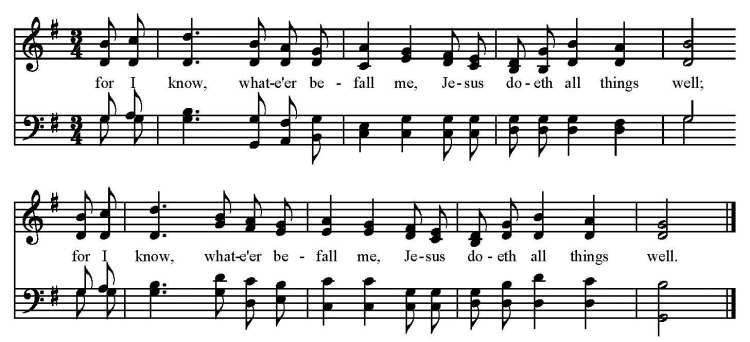

The repeat is a boon to the music, the words, and to our worship. The last two lines of stanzas 1 and 3 are summarizing; those of stanza 2 are climactic; and the repetition affords worshippers time to reflect on these ideas, even as it imprints them in our memory. The composer of the tune, Robert Lowry, instilled even this repetition with a sense of growth by changing its voice leading from one statement to the next:

The contrary motion between the outer voices in the first statement is followed by more interest in the internal voices in the second. Few hymnals today retain the change. The Baptist Hymnal (1991) calls for the first version twice through, whereas the Trinity Hymnal (1990) calls for the second version twice through! However, the reflective and mnemonic benefit of the repetition itself remains, and thus, in a sense, the tune leads us to remember our Guide.