Amazing Grace!

Faith’s Review and Expectation

John Newton, 1779

Addressed to anyone

| Amazing grace!—how sweet the sound— | |

| that saved a wretch like me! | Rom. 7:24 |

| I once was lost, but now am found, | Luke 15:6, 9, 24, 32 |

| was blind, but now I see. | Is. 29:18; Matt. 11:5; John 9:25 |

| ’Twas grace that taught my heart to fear, | Deut. 4:10; Ps. 34:11; Jer. 32:40; Matt. 3:7 |

| and grace my fears relieved; | Gen. 15:1; Ex. 14:13; Is. 43:1; Jer. 30:10 |

| how precious did that grace appear | Acts 8:35–39 |

| the hour I first believed! | |

| Thro’ many dangers, toils, and snares, | Ps. 91:3 |

| I have already come; | |

| ’tis grace has brought me safe thus far, | 1 Chr. 17:16 |

| and grace will lead me home. | 1 Chr. 17:17 |

| The Lord has promised good to me, | Num. 10:29 |

| his Word my hope secures; | Ps. 93:5; Titus 1:2 |

| he will my shield and portion be, | Ps. 18:30; Ps. 73:26 |

| as long as life endures. | |

| And when this flesh and heart shall fail, | |

| and mortal life shall cease, | |

| I shall possess within the veil | Heb. 10:19 |

| a life of joy and peace. | Ps. 16:11; Rom. 8:6 |

| [When we’ve been there ten thousand years, | The earth shall soon dissolve like snow, |

| bright shining as the sun, | the sun forbear to shine; |

| we’ve no less days to sing God’s praise | but God, who call’d me here below, |

| than when we’ve first begun.] | will be for ever mine. |

“The saying is trustworthy and deserving of full acceptance, that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners, of whom I am the foremost. But I received mercy for this reason, that in me, as the foremost, Jesus Christ might display his perfect patience as an example to those who were to believe in him for eternal life” (1 Tim. 1:15-16). The Apostle Paul understood how to write edifying autobiography. The focus of his autobiographical texts (1 Corinthians 15:8-10, the whole of 2 Corinthians, Galatians 1, etc.) is really always God, not Paul. He understood that the object of Christian faith is infinitely more interesting than the faith itself. Jonah understood this, too. So did Augustine. And so, probably, did the saint who gave his personal testimony at last week’s prayer meeting. There is a kind of Christian witness whom we love to hear because he presents us with yet more direct evidence of who God is: a sovereign and loving savior.

The hymn in front of us was written for a New-Year’s service, an occasion when worshippers traditionally reflect on whence they have come and whither they are going. The genius of the hymn is that its theme is really not the Christian’s life but rather grace: several concrete and related ways in which God’s generosity, at every turn, transforms the Christian’s life into something meaningful. “Amazing Grace!” affords us the opportunity to testify publicly to the divine grace that alone has delivered us, sustains us even now, and assures us of eternal life—using the psalmodic format of a catalog of the Lord’s wondrous deeds past, present, and future.

Like an honest church member moved to speak up at meeting, the hymn begins vehemently, even impulsively, with an exclamation and an interjection: “Amazing Grace! (how sweet the sound) that . . .” In the unpretentious humility of a self-professed wretch, it employs only monosyllabic words for the next stanza and a half. Grace is what amazes, not the speaker. We can almost taste the sweetness of God’s gifts as the alliterative S’s cause the tongue to tingle (coming after the Z in amazing: sweet, sound, saved, see). The one who is lost cannot merely return home. He must be found; that is, someone else must find him, and that is grace. The one who is blind cannot simply decide he is going to see now. Sight must be given to him. It turns out (stanza 2, see Eph. 2:8) that belief itself is a gift. Those who do not fear the Lord cannot on their own generate fear of the things that ought to be feared; they must be taught by the Spirit (1 Cor. 2:14). Ironically, the first two lines of stanza 2 circle back on themselves, for the relief of learning that Christ has already borne the penalty so that we don’t have to is precisely what frees us otherwise self-righteous sinners to fear God in the first place. Amazing.

As the sinner’s justification is accomplished by God’s free grace, so, too, is his sanctification. It was God who brought the justified sinner through the wilderness to the place where he now sings. God will continue to lead him all the way home to Canaan, and, with this, the hymn pivots from past to future at its exact midpoint, the end of stanza 3. Not only will any protection, contentment, joy, or peace that the Christian enjoys in the future be gifts from God, so, too, is the promise that he will enjoy them. Since the one who promises never lies, the Christian can live by hope. Hope, it turns out, is also amazing grace. In Newton’s original scheme, the poem looks swiftly through the rest of one’s life (stanza 4), to one’s death (stanza 5), and to the very end of the world (stanza 6, reproduced above in italics). But Newton’s gorgeous sixth stanza has for a long time now been universally displaced by an anonymous and somewhat random (abrupt shift in theme from grace to praise), jarring (shift in voice from first-person singular to first-person plural), ungrammatical (the verb tenses are incorrect, and “less” cannot modify a plural noun), and ambiguous (where is there? what is shining?) quatrain. But the substitution is not a total loss, for perpetual praise is a fetching idea, and our participation in it will be a gift.

The rugged contours and equally rugged embellishments of the tune AMAZING GRACE (or NEW BRITAIN as it’s sometimes called) match the plainspoken poetry. Music theorists would call them “pentatonic,” meaning that they contain only five scale-degrees: do, re, mi, sol, and la—but neither fa nor ti. It’s a melodic structure common in folk songs worldwide but uncommon in European art-music. Fa and ti do not appear in “Camptown Races,” “Ezekiel Saw the Wheel,” or “Old Dan Tucker.”

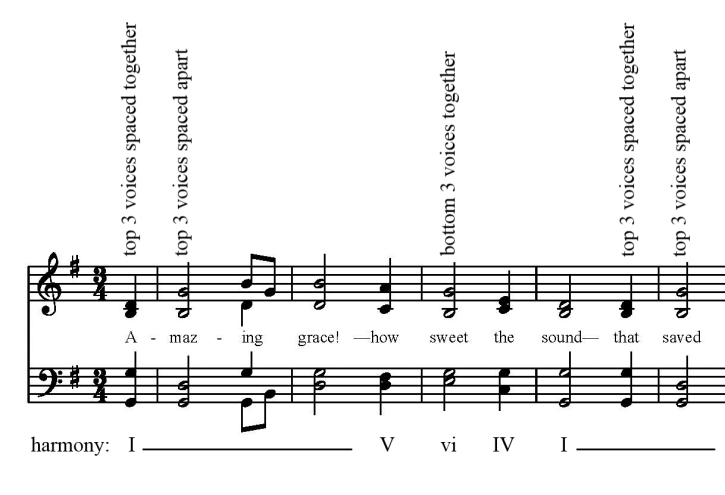

The tune illustrates the word “amazing” by means of the most forceful gesture in Western music: a fifth scale-degree (sol) rising to a first scale-degree (do) on the downbeat, which contrasts vividly with the descending steps of “how sweet the sound.” The harmony in Edwin O. Excell’s classic arrangement (1910), used in many hymnals, reinforces the sense of these melodic gestures. Not only does the soprano leap up to the second syllable of “amazing,” as dictated by the tune, but the tenor leaps down, so we swing from a chord in which the top three voices are spaced as closely together as possible to one in which they’re spaced apart, to produce the fullest sound on the accented syllable. (Other hymnals achieve this effect by assigning the first syllable to a unison, then moving to a chord for “-maz-.“) The first five notes of the tune (amazing grace) are harmonized by one chord in various voicings, but the next four notes (how sweet the sound) each have a different chord, and the resulting increase in harmonic richness works like onomatopoeia. Especially colorful is the E minor chord (labeled below with the Roman numeral vi) on “sweet”; now the bottom three voices are spaced closely—indeed, the alto is closer to the bass than it is to the soprano—to thicken the sound of the chord.

Line 2 of the poem (that saved a wretch like me) has exactly the same music as line 1 until the word “me.” Here it leaps up to high D (sol), the peak tone of the melody, and holds it for five beats to underscore Newton’s exclamation point. Incidentally, it works nicely in stanza 6, too, for “bright shining as the sun.” Line 3 provides some melodic contrast, being unlike the melody of lines 1 and 2, even as it does conclude like them, on D (sol), to establish a structural parallelism. Only line 4 ends on G (the first scale-degree, or home pitch); this withholding of a perfect cadence until the very end pictures the sense of “and grace will lead me home” in stanza 3.

To appreciate how well Excell’s harmonization prepares us for this final cadence, we must first back up and consider a melodic quirk of the tune. Of the thirty-five melodic notes in AMAZING GRACE, twenty-nine fall on the pitches G, B, and D (do, mi, and sol)—the pitches of the home, or “tonic,” chord (labelled above with the Roman numeral I). Only six notes of the melody are foreign to the tonic chord (falling on the pitches A and E). If we analyze the melody in four phrases, corresponding to the four lines of the stanza, we’ll notice that each of these six notes from outside the tonic chord occurs somewhere in the second halves of these phrases. Thus the melody itself implies an alternation between simple, tonic harmony in the first half of each melodic phrase or poetic line and something else in the second half of each (and we’ve noted above how neatly this fits the contrasting utterances of the poem’s opening). In Excell’s arrangement, the first halves of lines 1–3 (“Amazing grace,” “that saved a wretch,” and “I once was lost”) all share the same, unmoving tonic-harmony. The E minor chord in the first half of line 4, then, is without precedent and thereby alerts us to the possibility that line 4 might end in a different way, which it does. (Arrangements like those in Episcopalian and Lutheran hymnals that attempt to spice up the harmony with a vi chord at the beginning of line 2 paradoxically make the tune a bit tedious. We miss Excell’s harmonic differentiation between the first and second halves of the tune. There is no longer anything distinctive about the beginning of line 4, so it cannot cue the final cadence. If a congregation sings six stanzas, it may feel like it has done the same thing twelve times.)