Angels from the Realms of Glory

Good tidings of great joy to all people

James Montgomery, 1816; last stanza, Salisbury Hymn Book, 1857

Addressed to angels, shepherds, wise men, one another, and all creation

| Angels, from the realms of glory, | Luke 2:9 |

| wing your flight o’er all the earth; | |

| ye who sang creation’s story, | Job 38:7 |

| now proclaim Messiah’s birth: | |

| come and worship, | |

| worship Christ the new-born King. | |

| Shepherds in the fields abiding, | Luke 2:8 |

| watching o’er your flocks by night, | |

| God with man is now residing, | 2 Chr. 6:18; Rev. 21:3 |

| yonder shines the infant Light: | John 1:5 |

| come and worship, | |

| worship Christ the new-born King. | |

| Sages, leave your contemplations, | |

| brighter visions beam afar; | |

| seek the great Desire of nations; | Hag. 2:7 |

| ye have seen his natal star: | Num. 24:17; Matt. 2:2 |

| come and worship, | |

| worship Christ the new-born King. | |

| Saints before the altar bending, | Rev. 8:3; Luke 2:25, 37–38 |

| watching long in hope and fear, | |

| suddenly the Lord, descending, | Mal. 3:1 |

| in his temple shall appear: | |

| come and worship, | |

| worship Christ the new-born King. | |

| [Sinners, wrung with true repentance, | |

| doom’d for guilt to endless pains, | |

| justice now revokes the sentence, | |

| mercy calls you,—break your chains: | |

| come and worship, | |

| worship Christ the new-born King.] | |

| All creation, join in praising | Psalm 19:1; Rom. 1:20 |

| God the Father, Spirit, Son; | |

| evermore your voices raising | |

| to th’eternal Three in One: | |

| come and worship, | |

| worship Christ the new-born King. |

Some gifts are given with an exclusive recipient in mind but will nevertheless benefit many others. When a father gives his son a dog as a pet, the other siblings will enjoy the animal’s company, the chicken coop will enjoy its protection from foxes, the mother will enjoy its protection on afternoon walks, and the father will be glad that the dog shares in his vigilance over the safety of the household. None of this changes the reality that the dog was given to the son. So too, Christ did come to save sinners, but that does not negate the reality that his coming was out of love for the whole world, that it was the critical step in the redemption of all creation, in the reversal of the curse, and that it would bring great benefits even to the reprobate. We tend to think of Christ’s coming as if it were a gift given exclusively to us, which of course in one sense is completely true. Christ’s advent is a gift given to us which commonly benefits a multitude of others. James Montgomery’s hymn explains the breadth of benefits which comes from Christ’s advent. In the original version, his explanation culminates in the redemptive work of Christ (see bracketed stanza above). He begins, however, by pointing us to all the many things touched by Christ’s advent, and this is the main purpose of his hymn.

First, the angels. The rift created between God and man at the fall put us at enmity not only with God, but with the angels. This is clearer if we consider the frequency with which they are evoked to drive out, plague, or kill mankind in the book of Genesis. The coming of Christ signalled to the angels that the warfare was now over—God would restore us to himself. It makes sense then, as Montgomery points out, that those who were witness to our creation would rejoice over this important step toward our redemption like a faithful son rejoices when his prodigal brother is restored to the family.

The lower cast of the Hebrew class system comes next on Montgomery’s list. The second stanza may seem the weakest, since it seems only to paraphrase the familiar passage in Luke’s gospel, whereas the others evoke many biblical images at once. But Montgomery is not merely paraphrasing Luke. Notice that he sets up a metaphor. The shepherds abide in their fields and watch over their flocks (a direct quotation from Luke) but God resides with his flock—mankind—and while the shepherds maintain their flocks in darkness, God brings his own light in the form of the natal star. This metaphor is emphasized even in the rhyming words (the most memorable part of a hymn). “Abiding” is contrasted with “residing” and “night” with “light.”

The third stanza turns to the wise men who are encouraged to desire “brighter visions” even than the ones which they can derive from their own contemplations. Christ’s advent would shake all nations, not just Israel, as we learn in Haggai. And though the entirety of those nations will never turn to Christ, a portion from each, we know, will come to him.

Beautifully, Montgomery turns our attention to the “Saints before the altar.” He uses the language of the eighth chapter of John’s Revelation but his “watching long in hope and fear” suggests exactly which saints he means—Simeon and Anna. Both waited in expectation of the coming Messiah, informed by prophets like Malachi, whom Montgomery evokes in the next line. That they are referred to as saints is telling. They are saints in the same way that Abraham and Isaac are saints in the eleventh chapter of Hebrews. Christ brings salvation to them, but this is in fulfilment of the promise to which they already hold. This is not the group for whom we generally think Christ came. He himself said that he came for the lost sheep of the house of Israel and Simeon and Anna were anything but lost. Nevertheless, Christ’s coming does fulfil all of the pictures of the Old Testament and he does redeem the saints of that age as well as of our own.

Indeed, even all creation benefits from the coming of Christ and it is there that we turn in the last stanza. The repeated refrain was part of Montgomery’s original conception. It turns every verse into an exhortation to whomever was mentioned in the stanza’s first line.

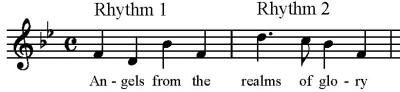

Happily, the text is set in the Trinity Hymnal to REGENT SQUARE which is perfectly suited to it. The tune has two basic rhythmic patterns, evident in the first two measures.

The tune bounces athletically across the octave, repeating these two rhythmic ideas throughout.

What makes the hymn and tune so memorable is, predictably, its reprise. The reprise builds sequentially by repeating rhythm 2 twice, the second time higher than the first, and then climaxing on a high E while returning to rhythm 1 to conclude. This quickly building reprise, with its climbing trajectory and relatively high final note (a high B-flat is by no means the middle of a congregation’s range) make the declarative ending of the hymn so powerful. One feels as though the angels must really obey such a prayer when it comes out at such a high volume. And the declaration itself, powerful and loud, helps us to remember that we—the sinners wrung with true repentance—are not the only ones who must come to worship.