Arise, My Soul, Arise

Behold the Man!

Charles Wesley, 1742

Addressed to oneself and to each other

| Arise, my soul, arise, | Ps. 42:5 |

| shake off your guilty fears; | |

| the bleeding Sacrifice | Heb. 9:13–14 |

| in my behalf appears: | |

| before the throne my Surety stands, | Heb 12:2 |

| my name is written on his hands. | Is. 49:16 |

| He ever lives above, | |

| for me to intercede, | Heb. 7:25, John 17:9 |

| his all-redeeming love, | Eph. 1:7 |

| his precious blood to plead; | Luke 22:20, Rom. 5:9 |

| his blood atoned for ev’ry race, | Rev. 5:9 |

| and sprinkles now the throne of grace. | Heb. 4:14–16 |

| Five bleeding wounds he bears, | John 20:27 |

| received on Calvary; | |

| they pour effectual prayers, | |

| they strongly plead for me. | Rom. 5:9; 1 John 2:1–2 |

| “Forgive him, oh, forgive,” they cry, | |

| “nor let that ransomed sinner die!” | Rom. 8:33 |

| My God is reconciled; | Rom. 5:10 |

| his pard’ning voice I hear; | Zech. 3:4 |

| he owns me for his child, | Gal. 3:26 |

| I can no longer fear; | |

| with confidence I now draw nigh, | Heb. 4:16 |

| and “Father, Abba, Father!” cry. | Rom. 8:15; Gal. 4:6 |

In Edmund Spencer’s famous poem The Faerie Queene, the hero of the first book (who is an allegorical representative of the Christian’s soul) finds himself unwittingly in the cave of Despaire (represented by Spencer as an ogre who leads men to suicide). Though the hero is brave, when Despaire shows the hero his many sins against God, and how he is likely to incur God’s wrath all the more if he continues to live, the brave hero considers ending his own life. Happily, the hero is saved by his beloved who storms into the cave and says the following:

Come, come away fraile feeble, fleshly wight,

Ne let vaine words bewitch thy manly hart,

Ne diuelish thoughts dismay thy constant spright.

In heavenly mercies hast thou not a part?

Why shouldst thou then despeire, that chosen art?

Where iustice growes, there grows eke greater grace,

The which doth quench the brond of hellish smart,

And that accurst hand-writing doth deface,

Arise, Sir knight arise, and leave this cursed place.

(Book I, Canto IX, stanza 53)

We cannot know whether Charles Wesley had the famous last line of this stanza in his mind when he began this hymn, but the coincidence of ideas and words is striking, not least in what it informs us of the constant struggle which Christians have faced to overcome despair—in Spencer’s sixteenth century as much as in Wesley’s eighteenth.

The “guilty fears” are intentionally undefined in the first line of the hymn, but this is not vagueness on Wesley’s part. What those fears are will become clear as the hymn progresses, even as will the reasons to shake them off. The first stanza focuses on the reasons why we ought not to fear—the “bleeding Sacrifice” and the “Surety.” Moreover, our union with Christ is recorded even upon his hands. The second stanza turns our attention to Christ, not as immolation but as priest. He intercedes on our behalf, offering up his love for us and his own blood. At this point, it may seem like Wesley has sufficiently discussed the intercessory power of Christ. Wisely, however, Wesley stays on his original topic. The purpose of this hymn is to encourage saints to rest comfortably in the saving work of Christ. Like Spencer, who gives three reasons why his hero is not to despair, we here have three stanzas to comfort our fearful souls. In the third one, Wesley engages the image of Christ’s wounds. The image is vividly portrayed, for the wounds are “bleeding” and “pour effectual prayers” along with that blood. And with that blood comes atonement. Wesley focuses his attention, in the last stanza, on the reconciliation of man with God. It is here that we finally understand clearly why our soul was to be afraid. We were rightly afraid to approach God, since we were at enmity with him. The redeeming work of Christ, however, reconciles us to him and, as this stanza argues, he adopts us into his family. The hymn begins with a fearful sinner who is ashamed to approach the throne of God. It ends with a son crying out to his “Abba, Father.”

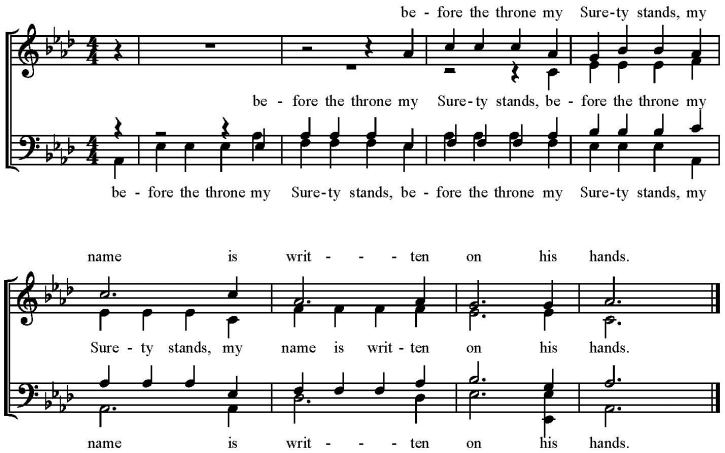

Louis Edson’s tune LENOX was first used in 1782 to set Isaac Watt’s paraphrase of Psalm 148 and was, in its original form, a somewhat complicated fuging tune (where one voice begins a line with the others entering slightly later). To get a sense of what the original tune was like, you can substitute the following for the last two systems in the Trinity Hymnal version (the tenor voice has the melody here):

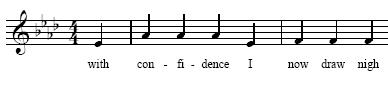

The editors of the Trinity Hymnal have presented a simplified version of the tune, but even in this form it serves Wesley’s text well. The tune consists of two sections, which are each self-contained. The first half of the tune ends in a satisfying way as if it were a short hymn tune in and of itself. Such a gesture is common among early American fuging tunes because it prepares the listener for the fuging passage which would normally then follow. One could think of the first half of such a tune like the slow ascent to the summit on a roller coaster. Once at the top, the cart seems to stop for a moment as if the ride were already over, only to plummet into something more interesting. In our version of the tune, the second half, though simplified, is still very effective as a melodic release because it consists of a single idea which is then reiterated in a more satisfying way. The beginning idea:

with its inconclusive ending on “la,” is moved up

and concludes with a thrice-repeated “do.” This three-fold “do” derives from the first three notes of the tune (see measure 1) and makes the gesture all the more “confident.” Just as the text moves from fear to security, so does the tune, as it moves to that familiar repetition of the tonic note and ends with a very sturdy cadence as a setting for each stanza’s reassuring and conclusive last line. Like the hero from Spencer’s poem, the more we hear about grace, the less cause we have for despair and fear.

LENOX

LENOX (1782)