At the Name of Jesus

Caroline M. Noel, 1870

Addressed to one another

| At the name of Jesus | Phil. 2:10 |

| ev’ry knee shall bow, | Is. 45:23 |

| ev’ry tongue confess him | Phil. 2:11a |

| King of glory now. | Ps. 24 |

| ’Tis the Father’s pleasure | |

| we should call him Lord, | Phil. 2:11b |

| who from the beginning | |

| was the mighty Word. | John 1:1 |

| At his voice creation | John 1:3 |

| sprang at once to sight, | |

| all the angel faces, | |

| all the hosts of light, | Ps. 33:6 |

| thrones and dominations, | Col. 1:16 |

| stars upon their way, | Job 38:31-33 |

| all the heav’nly orders | Jer. 33:25 |

| in their great array. | |

| Humbled for a season | 2 Cor. 8:9; Phil. 2:7-9 |

| to receive a name | |

| from the lips of sinners | |

| unto whom he came, | |

| faithfully he bore it | Heb. 2:17; 3:2 |

| spotless to the last, | |

| brought it back victorious, | Rom. 14:9 |

| when from death he passed. | |

| In your hearts enthrone him; | Eph. 3:17; Col. 3:15 |

| there let him subdue | Col 1:13 |

| all that is not holy, | |

| all that is not true: | |

| crown him as your Captain | Heb. 2:10 (KJV) |

| in temptation’s hour: | |

| let his will enfold you | Phil. 2:5 |

| in its light and pow’r. | Eph. 1:18 |

| Brothers, this Lord Jesus | |

| shall return again, | Acts 1:11 |

| with his Father’s glory, | Matt. 16:27 |

| with his angel train; | Matt. 25:31; Rev. 19:14 |

| for all wreaths of empire | Matt. 28:18; Eph. 1:21; Rev. 1:5; 19:16 |

| meet upon his brow, | |

| and our hearts confess him | |

| King of glory now. |

It is neither by chance nor an indication of theological imbalance that the richest section of many hymnbooks is that devoted to Christ’s estate of exaltation. The confluence of divine majesty and gracious salvation to be seen in his resurrection, his ascension, his sitting at the right hand of the Father, and his second coming stirs even the most prosaic of saints to make melody.

Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion!

Shout aloud, O daughter of Jerusalem!

behold, your king is coming to you;

righteous and having salvation is he. (Zech. 9:9)

In John’s account of heavenly worship, the Lamb’s taking of the scroll prompts a great outburst of song—indeed, the “new song”—and acclamation from “every creature in heaven and on earth and under the earth and in the sea, and all that is in them” (Rev. 5). We need not wait till heaven to set forth this theme that we are destined to sing.

Among hymns on the topic, Caroline Noel’s “At the Name of Jesus” is useful for its assertion of the great and ironic truth, implicit in both the Zechariah passage and the Revelation passage just quoted, that Christ’s exaltation is grounded in his humiliation. The king is mounted on a donkey; the Lion of the tribe of Judah is the Lamb who was slain. The hymn, following its model in Philippians 2:6-11, takes as its fulcrum (stanza 3) the doctrine that Jesus was humbled for a season to receive the covenant name of God. He came as a suffering servant and underwent the cursed death of the cross so that creation itself might be restored and that sinners especially might be ransomed to, in turn, serve him as “Lord.” He is the “King of glory,” who alone is qualified to ascend to heaven and to bring us with him.

The preceding lines (stanza 2) prepare us for the full force of this irony by noting his exalted role in creation, particularly in the creation of things bigger than we. “By the word of the Lord the heavens were made, and by the breath of his mouth all their host” (Ps. 33:6). We have here a list of angelic and celestial wonders beyond our perception, to say nothing of our understanding, and all of which were made through the Word. (Note how the grammar of the list breaks down the two-lines-per-clause pattern of stanza 1 into awestruck phrases of one line each.) Thus the second and third stanzas together present a trenchant contrast between Christ’s pre-incarnation glory and the humility with which he took the form of a servant and obeyed the Father to the point of death. Christ’s subsequent victory made his latter exaltation even more glorious than his former exaltation.

The last two stanzas follow seamlessly from the third, with stanza 4 making application for our walk in sanctification, and stanza 5 noting the exaltation that will be Christ’s when he returns in judgment.

The poetry is full of successful details. At the beginning, for example, alliteration coordinates with rhyme to support the impressive allusion to Psalm 24 in line 4. The sound of the word “name” in line 1 constricts to the more closed vowel in “knee” in line 2. These words fall on the same syllable of their respective lines, and Vaughan Williams’s tune plays up the relationship between “name” and “knee” by initiating both lines with the same three-note gesture. Then we seem to move on to different sounding words in line 3, only to return to the alliterated sound at the arrival of the rhyme in line 4 (“now”) with its very open vowel.

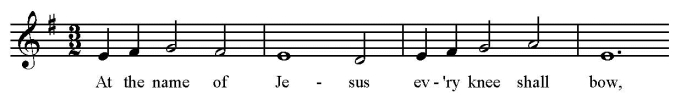

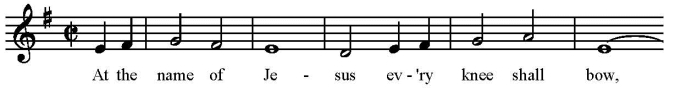

The tune KING’S WESTON is a masterpiece. It is easier to sing than the composer’s earlier SINE NOMINE (“For All the Saints”) because its rhythm is more repetitive, there are fewer melodic leaps, and the placement of syllables remains the same from stanza to stanza. Yet the tune is catchy and distinctive. For all its repetitiveness, the rhythm comes alive because of an ongoing equivocation in meter. Should we feel it in three, as published?

Or in two?

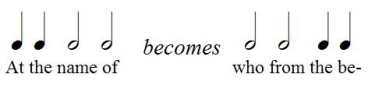

The basic rhythm (short-short-long-long-LONG) repeats six times as the pitch climbs from G at “name” to A at “shall,” to B at “tongue,” to a climactic D when the name is uttered: “call him Lord.” (It’s interesting how some congregants instinctively know to crescendo on “Lord.”) Then, having built up considerable energy, the melody releases and reverses direction in an extravagant descent from high E to low E, marked by a corresponding reversal of the basic rhythm:

Throughout, Vaughan Williams’s handling of the minor mode reinforces the gravity of the text. Nobody singing this tune could “confess him King of glory now” with glibness.