Be Still, My Soul

Katharina von Schlegel, 1752; trans. by Jane Borthwick, 1855

Addressed to one’s soul

| Be still, my soul: the Lord is on your side; | Ps. 37:7; 46:10; 116:7 |

| bear patiently the cross of grief or pain; | Luke 14:27 |

| leave to your God to order and provide; | Ex. 14:14 |

| in ev’ry change he faithful will remain. | Deut. 7:9; Is. 40:8 |

| Be still, my soul: your best, your heav’nly Friend | Prov. 18:24 |

| through thorny ways leads to a joyful end. | Ezek. 28:24; Hos. 2:6; 2 Cor. 12:7 |

| Be still, my soul: your God will undertake | |

| to guide the future as he has the past. | Num. 14:11; Deut. 1:30–31 |

| Your hope, your confidence let nothing shake; | Heb. 3:6 |

| all now mysterious shall be bright at last. | 1 Cor. 13:12 |

| Be still, my soul: the waves and winds still know | Ps. 65:7; 107:29; Mark 4:39–41 |

| his voice who ruled them while he dwelt below. | |

| Be still my soul: when dearest friends depart, | 1 Thess. 4:13 |

| and all is darkened in the vale of tears, | |

| then shall you better know his love, his heart, | Ps. 31:7; 1 Pet. 4:19 |

| who comes to soothe your sorrow and your fears. | Zeph. 3:15 |

| Be still, my soul: your Jesus can repay | |

| from his own fullness all he takes away. | Job 1:21; 42:10–17; Matt. 19:29; 1 Pet. 5:10 |

| Be still, my soul: the hour is hast’ning on | Zeph. 1:14; James 5:7–8 |

| when we shall be forever with the Lord, | 1 Thess. 4:17 |

| when disappointment, grief, and fear are gone, | Rev. 21:4 |

| sorrow forgot, love’s purest joys restored. | |

| Be still, my soul: when change and tears are past, | |

| all safe and blessed we shall meet at last. | 1 Cor. 13:12 |

Anyone with any sensitivity toward others will attest that the person in grief or trial will take more comfort from a quiet and calming word than from joining in with him in the throes of grief. The question is, of course, how to say something comforting without saying too much. How many of us have faced a difficult and awkward half-hour in some hospital, doctor’s office, or nursery with a grief-stricken friend and searched for words which, when they came, likely did more harm than the long silence which preceded them? A hymn which hopes to bring comfort to those in grief stands between two dangers. On the one hand, it might dwell overlong on the cause of grief and risk opening wounds while trying to swab them. On the other, it may say too little, and give no real comfort at all. Scripture teaches that the only lasting comforts in grief are the double certainties of God’s sovereign control and his steadfast love for us. This simple hymn avoids a melodramatic emphasis on sorrow and grief, and turns all of its poetic energies toward God’s sovereign rule, while neither incriminating God (by making him out to be the author of evil) nor dethroning him from his complete rule over all things that come to pass. The hymn preaches the sovereignty of God to the Christian who has just experienced a dark providence in the same way that a good Christian friend might do the same. We do not turn to the crying mother who has just miscarried and scold her with the rod of God’s omnipotence. We kindly whisper that she can take courage to know that God loves her and controls all the events of her life with that very love in mind.

In the moment of its occurrence, we cannot make sense of any grief but to hope it a necessary turn which sets us more directly on the path God has cut for us. Accordingly, this hymn includes gentle images of a journey throughout. Most obvious of these is the last line of the first stanza, but the second stanza’s “guide your future” and the third stanza’s “vale of tears” also suggest travel. The second stanza compares emotional turmoil to environmental conditions that disrupt travel—“the waves and winds”—only to remind us that the Lord sovereignly rebuked these with the very words that we now address to ourselves: “Peace! Be still!” (Mark 4:39) The metaphor implies that he who turned a meteorological storm into a “great calm” for his disciples will do the same to the psychological storms that hit us. “Be still, and know that I am God” (Ps. 46:10).

The end of the journey is predictably announced in the last line of the last stanza. Our journey ends in the beatific union with God. The exact meaning of “we” in this stanza is likely mistaken by the congregant, for we have learned to emphasize (at the expense, perhaps, of more important eschatalogical promises) the reunion with souls that, as the apostles put it, “have fallen asleep.” “We,” in the second line of stanza 4, refers to those of us yet here below. And the union there is between us and the Lord. Because of the third stanza’s reference to the departure of “dearest friends,” we are tempted to read “we shall meet at last” as an allusion to the reunion of separated humans. Indeed, this would round off the hymn beautifully. It would move from vague grief, to real loss, and finally to loss of our own lives—which turns out to be joy since only then will we be united with our loved ones over whose loss we mourned (this is, in fact, the sense of the original German, which concludes, “we will see each other again”). There seems to be more to the “we” than that, however. The main characters of this hymn are the Christian’s soul and the Lord. The departed friends are plural—“dearest friends depart”—and not personalized. The meeting, “at last,” is between us and the Lord, who has guided us through our grief to permanent joy.

Sibelius’s tune is as pacific as this text. It develops clearly, with gorgeous counterpoint between the outer voices, but without the usual tension-and-release structures common to hymn tunes. Such tension would risk melodrama here and perhaps dislodge the gentle comfort of the text. Notice that the melody’s first phrase merely hovers around the third scale-degree (the pitch A), which gives it none of the typical question-like gestures common to first phrases. Then, this static first phrase is almost exactly repeated.

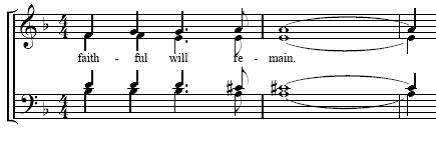

Like the first half, the tune’s second half is made up of music that is repeated almost exactly. In its first presentation, it comes to an unusual cadence on a sonority that does not belong to the tune’s home key:

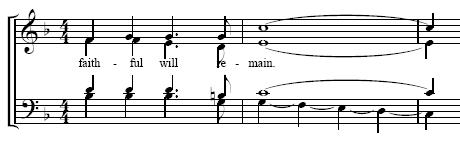

This cadence is unexpected and yet not jarring. It does not set up the usual melodic tension that would normally be expected at such a moment in another hymn tune. Indeed, the expected cadence would be something like this:

The expected cadence (what musicians call a half-cadence) would set up tension which could then be resolved by the cadence at the tune’s end (what musicians call an authentic cadence). Sibelius’s choice is a wiser one. The arrival on an A chord radiantly confirms the promise of the emphasized third scale-degree in the melody’s first half (note that, whereas the normal A chord in this key is minor, this one is chromatically transformed to major), even as it avoids the kind of tension that can jar the soul struggling with grief. The music of lines 5–6 is, as mentioned, a near-repeat of the music of lines 3–4, with only the last two notes altered to form a satisfactory final cadence. So, without creating undue tension, the tune nevertheless progresses. The tune, like the text, says no more than it must. Anything more would be less of a comfort.