Children of the Heavenly Father

Lina Sandell-Berg, 1855; translated by Ernst W. Olson, 1925

Addressed to one another

| Children of the heav’nly Father | Ps. 103:13; Matt. 23:9 |

| safely in his bosom gather; | Is. 40:11 |

| nestling bird nor star in heaven | Job 38:32; Ps. 84:3; 147:4; Luke 12:7 |

| such a refuge e’er was given. | Joel 3:16 |

| God his own doth tend and nourish, | Ex. 16:1–36 |

| in his holy courts they flourish; | Ps. 92:13 |

| from all evil things he spares them, | Ps. 121:7 |

| in his mighty arms he bears them. | Ps. 89:13; Is. 46:3–4 |

| Neither life nor death shall ever | Rom. 8:38 |

| from the Lord his children sever; | |

| unto them his grace he showeth, | Eph. 2:7 |

| and their sorrows all he knoweth. | Ex. 3:7; Heb. 4:15 |

| Praise the Lord in joyful numbers, | Rom. 15:11 |

| your Protector never slumbers; | Ps. 121:4 |

| at the will of your Defender | Rom. 8:37 |

| ev’ry foeman must surrender. | |

| Though he giveth or he taketh, | Job 1:21 |

| God his children ne’er forsaketh; | Heb. 13:5 |

| his the loving purpose solely | |

| to preserve them pure and holy. | Rom. 8:28 |

| More secure is no one ever | |

| than the loved ones of the Savior; | |

| not yon star on high abiding | |

| nor the bird in home-nest hiding. |

Hymn-singing congregations often mistake children’s hymns for hymns aimed at a wider audience. Consider, for example, William Bradbury’s “Savior, like a Shepherd Lead Us,” which was first published in a book called Hymns for the Young but is now considered a hymn for the whole congregation. This is not at all to argue against singing children’s hymns in congregational worship, but only to point out that it is best when we know that we are doing so. The converse problem happens much less often. It is rare indeed that we mistake for a children’s hymn a hymn that is really aimed at a wider audience. Such is the case, however, with Lina Berg’s hymn printed above. Because its opening line refers to children, because its text is simple and tune placid, we tend to think it a hymn for children or at least a hymn about children. Upon a moment’s reflection, however, we find it to be both for and about us. Children may benefit from a reminder of their security in God, but the apprehensions to which this text speaks (“evil things,” “death,” “sorrows,” and “foeman”) are not the apprehensions of the playground or schoolroom. Scripture refers to God’s people as children often enough for us to recognize ourselves in the “children” of the first line.

The hymn, for all its simplicity, is surprisingly rich in scriptural allusion. As the references listed above will relate, practically every line is closely connected not only with the ideas but the actual wording of Scripture passages which relate to the hymn’s overall theme of security. The first stanza makes a Psalm-like merism (where two opposite ideas include an entirety) of stars in heaven and birds in a nest. The safety which both have, though vastly different in kind, shows us the nature of God’s care for us. We are preserved because we are exalted above even the stars in his love for us, and we are made humble like the brood described in Matthew 23 and Luke 13. So beautiful is this double-sided comparison that the hymn’s translator, Ernst Olson, returned to it of his own accord, quite apart from his model, in the version which we now use. His doing so could not but strengthen the poem, for it forces the singer back to the ideas which originally confronted him in the first stanza. We are protected by God who both raises us up and nestles us in.

The internal verses are no less beautiful if perhaps less rich in poetic conceit. Compare the last couplet of the second stanza with the first couplet of the fifth. In the first instance, God spares us from “all evil things” but in the second he “taketh.” This obvious reference to Job in the fifth stanza helps us to realize that the things which God takes away are good only in a subordinate sense. They are not the ultimate good for which we were made. Likewise, the trials he brings are not altogether evil, but temporary hardships administered by evil ones under the over-rule of a beneficent God for our good and for his glory.

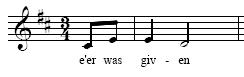

The tune contributes as much as the text to our thinking this a children’s hymn. Its single insistent rhythm never fails:

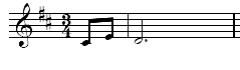

Indeed, this little motif so dominates the tune (its eight appearances comprise the tune’s entirety) that one cannot help but apply its musical meaning to the text directly. The little flutter which begins the motif calms immediately down to settled quarter notes, like the two quick breaths through the nose which often append a sob that has been moderated by good sense. The regularity of the motif turns even the tune’s final cadence to:

when we might be justified in expecting something like:

because of its rhythmic finality. The tune’s actual ending is better, because it deflates the harshness of the expected cadence and avoids any glibness (a fatality when setting a text on security).

That the motif’s constant repetition turns this tune into a kind of nursery melody need not prompt us to think it only for youngsters. “Truly, I say to you, unless you turn and become like children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven” (Matt. 18:3). Congregants who sing this song with sincerity are doing something that happens in nurseries all the time: they are humbling themselves and acknowledging their utter dependence on someone else’s protection and provision.