Christ the Lord is Risen Today

Hymn for Easter-Day

Charles Wesley, 1739; with Alleluias (Praise the Lord!) inserted every line

Addressed to one another

| “Christ the Lord is ris’n today,” | Luke 24:34; Matt. 28:6 |

| sons of men and angels say; | |

| raise your joys and triumphs high; | Is. 24:14; 2 Cor. 2:14 |

| sing ye heav’ns, and earth, reply. | Is. 44:23; 49:13 |

| Vain the stone, the watch, the seal; | Mark 16:4; Matt. 27:65-66; 28:4 |

| Christ has burst the gates of hell: | Matt. 16:18 |

| death in vain forbids his rise; | 1 Cor. 15:20 |

| Christ has opened paradise. | Rev. 2:7; 3:7-8 |

| Lives again our glorious King; | |

| where, O death, is now thy sting? | Hos. 13:14; 1 Cor. 15:55b |

| Once he died, our souls to save; | Rom. 6:10; 1 Pet. 3:18 |

| where thy victory, O grave? | 1 Cor. 15:55a |

| Soar we now where Christ has led, | 1 Cor. 15:20-23; Eph. 2:6 |

| foll’wing our exalted Head; | Eph. 4:15 |

| made like him, like him we rise; | 1 Cor. 15:49 |

| ours the cross, the grave, the skies. | Gal. 6:14; Col 2:12–14; Eph. 1:3 |

| Hail, the Lord of earth and heav’n! | Heb. 1:10 |

| Praise to thee by both be giv’n; | Ps. 69:34 |

| thee we greet triumphant now; | |

| hail, the Resurrection, thou! | John 11:25 |

Christians rejoice over the resurrection of Christ. Sometimes our reflection on it brings propositional theology and sometimes it merely brings (if one can say “merely” of such a word) alleluias. Charles Wesley’s hymn begins by declaring the resurrection of Christ, a declaration we know from Scripture to have been on the lips of men and angels even in those first hours after it occurred. The rest of the hymn calls others to share in the words of the opening line, reflects on its meaning, and declares that word given to us by heaven—“alleluia.”

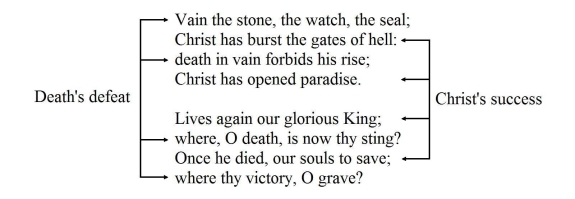

The four couplets in stanzas 2 and 3 present a back-and-forth contrast between Death and Christ:

Each declaration of death’s powerlessness in stanza 2 is immediately explained in terms of what Christ has done. Then the order is reversed in stanza 3 with Christ’s deeds, described in lines 1 and 3, eliciting taunts of death in lines 2 and 4.

The fourth stanza asserts our union with Christ, following the theology of 1 Corinthians 15, which Wesley has already been mining. Notice the strength of the medial break in the third line: “made like him, like him we rise.” The immediate repetition of the phrase “like him” forces the singer to apprehend the point of the stanza. Christ is the firstfruits of the resurrection.

Better yet, in stanza 5 the singer simply acclaims him as “the Resurrection,” following John 11:25. The last line of Wesley’s hymn draws our attention to the first. Not only is Christ risen, he is the resurrection.

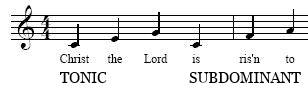

The 1990 edition of the Trinity Hymnal agrees with twentieth-century Methodist and Baptist practice in pairing the text with EASTER HYMN, a tune first published in 1708 for use with another hymn with a similar opening line: “Jesus Christ Is Risen Today.” (The Trinity Hymnal matches that text to LLANFAIR, but many other hymnals assign these tunes the other way around. The resulting confusion is compounded by the existence of yet other hymns with similar titles.) The tune begins with acrobatic leaps, first up the tonic chord and then up the subdominant:

By doing so, the tune climbs higher as it describes the resurrection. It also expresses the jubilation of our hearts. The third line relates to the text even more closely. The phrase

with its repeated pattern of ascending stepwise motion which climbs to the tune’s highest note makes a perfect setting for the third line of every stanza. Consider some of the words which fall on that high E as sufficient evidence: “high” (stanza 1); “rise” (stanzas 2 and 4); “save” (stanza 3).

The interpolated alleluias deserve special attention. They repeatedly interrupt the poem, as if the congregation cannot wait until the end to erupt in praise. That almost every Easter hymn includes such exclamations is no coincidence, for they have marked Easter worship throughout the history of the church—beginning with that of our Lord himself, who led the disciples in singing hallel psalms in preparation for his death and resurrection (Matt. 27:30). Thus, although the first publication of Wesley’s poem in 1739 (without tune) included no alleluia, it is likely that they were assumed. Some subsequent versions of the hymn have included alleluias; others have not. The alleluias of EASTER HYMN, the tune considered here, are a pleasure to sing. They approach the melodic expansiveness of the celebrated eastertide alleluias of medieval chant in their florid melismas and predictable stepwise cadence, allowing us to draw from Christendom’s earlier songs for that “most high of holidays.” But unlike medieval chant, the complexity of which excludes the untutored congregant, our alleluia trope is open even to the smallest children because of its repetitive nature. Here we can all lift up our voices to all creation while joining in with the sons of men and angels who have sung ebullient alleluias through the ages, as we rejoice in the resurrection.