Come, Ye Sinners, Poor and Wretched

Come and Welcome, to Jesus Christ

Joseph Hart, 1759

Addressed to sinners

| Come, ye sinners, poor and wretched, | Luke 15:1; Matt. 5:3 |

| weak and wounded, sick and sore; | Ps. 72:13; Rom. 5:6 |

| Jesus ready stands to save you, | Matt. 22:4; Rev. 3:20 |

| full of pity joined with pow’r: | Is. 63:9 |

| he is able, | Heb. 7:25 |

| he is willing; doubt no more. | 1 Tim. 2:4; 2 Pet. 3:9 |

| Come, ye needy, come and welcome, | Ps. 72:12; Luke 9:11; Rom. 15:7 |

| God’s free bounty glorify; | Rom. 9:23; Eph. 1:6 |

| true belief and true repentance, | 1 Pet. 1:20–21; Acts 5:31; 2 Cor. 7:10 |

| ev’ry grace that brings you nigh, | |

| without money, | Is. 55:1; Rev. 22:17 |

| come to Jesus Christ and buy. | |

| Come, ye weary, heavy laden, | Matt. 11:28 |

| bruised and broken by the fall; | Is. 42:3; Matt. 12:20 |

| if you tarry till you’re better, | Matt. 9:12 |

| you will never come at all: | Rom. 3:20 |

| not the righteous— | Luke 5:32 |

| sinners Jesus came to call. | |

| Let not conscience make you linger, | Matt. 15:21–28 |

| nor of fitness fondly dream; | Matt. 19:26 |

| all the fitness he requireth | |

| is to feel your need of him; | Luke 18:13–14 |

| this he gives you; | John 16:8 |

| ‘tis the Spirit’s rising beam. | 2 Cor. 4:6 |

| Lo! th’incarnate God, ascended, | Acts 2:33 |

| pleads the merit of his blood; | Heb. 9:12 |

| venture on him, venture wholly, | |

| let no other trust intrude: | |

| none but Jesus | John 14:6 |

| can do helpless sinners good. |

Each story of coversion has its own nuances, but they all have in common certain realizations on the part of the convert. The questions we raise and the answers we receive while under the conviction and power of the Holy Spirit may be spaced out over years or may follow one on the other in a matter of minutes but they all look quite similar. This hymn walks us through those questions and answers. In our former state, wallowing in sin and suffering its consequences, the first question is put simply: is there help for me? We hear in the first stanza that “Jesus ready stands to save you, full of pity joined with power.” But can Christ really save us? “He is able, he is willing; doubt no more.” “But why,” we wonder, “would he do this?” We learn, in the opening of the second stanza that he does this to bring glory to himself through his free bounty. “Very well then,” we say, “but what must I do?” When we learn that we must have “true belief and true repentance,” we are prone to despair. We haven’t either of those things. How could we gain them? The hymn replies using Christ’s own idiom—“without money, come to Jesus Christ and buy” (Rev. 3:17–18). But how can we come? We are “bruised and broken by the fall” to such an extent that it seems we cannot come to repentance and belief, though they are just what we need to be healed of our bruises. We find ourselves like the man who cannot afford a new suit to wear to the job interview because, after all, he has no job. We learn right away the danger in this type of thinking. “If you tarry till you’re better, you will never come at all.” It turns out that we are apparelled in just the kind of rags that Christ expects us to be wearing. There’s no need to buy ourselves a suit. He will provide one with the job. “Not the righteous—sinners Jesus came to call.” But surely we must be able to do something to make ourselves worthy of Christ’s salvation? Perhaps, since he asks us to feel needy (stanza 4, line 4) we can work up this feeling in ourselves and thereby become fit? But no, again. “This he gives you; ’tis the Spirit’s rising beam.”

If we can do nothing to win Christ’s favor, we have nothing to hope on for our salvation but that which Christ gives us. And this is the point of the last stanza. It begins with an image of the ascended Christ pleading on our behalf to God the Father. The poem then commands, as does the Scripture of the Old and New Testament, to venture on Christ alone for our salvation. Throughout the hymn we are warned against the intrusion of ideas contrary to this command. The hymn ends fittingly by reminding us that “none but Jesus can do helpless sinners good.”

Joseph Hart found a way to write with poetic beauty without compromising accessibility on a topic which, of all topics, must be accessible. One of the ways by which his verse rises above the hum-drum is alliteration. Consider line 2 of stanza 1 where paired alliteration accents our pitiable state. The same device is used in the second line of stanza 3, again to point out our misery without Christ. The first stanza’s “pity, joined with pow’r” explodes like “full” things often do. Line 2 of stanza 2 is also forcefully alliterative. He could have as easily written “and your Savior glorify.” Likewise, “if you tarry till you’re better” from the third stanza could have as easily been “if you wait until you’re better,” but with much less success. We “fondly” dream of “fitness” in the fourth stanza and then go on to “feel” our need of Him. Then beautifully, in the summary final stanza, the alliteration vanishes. The change snaps the reader to attention like a glass of cold water.

Every stanza consists basically of three syntactical units of two lines each (except for the enjambment in stanza 2, lines 3–6). Both of the first two of these units share the same rhythm: an eight-syllable line followed by a seven-syllable line. But the third pair of lines, containing as they do the key promise of every stanza, expands to twelve syllables (a threefold repetition of a four-syllable phrase) followed by seven syllables. The bar form of BRYN CALFARIA, the tune to which this hymn is set in the Trinity Hymnal, fits this pattern perfectly. The first and second pairs of lines are given to the A section and the remainder to the B section. (The tune CAERSALEM fits this pattern, too. The one used in most editions of The Sacred Harp, BEACH SPRING, also fits, but with a slighty different repetition scheme: “He is able, he is able, he is willing; doubt no more. He is able, he is able, he is willing; doubt no more.[1]).

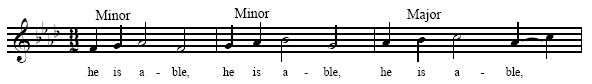

BRYN CALFARIA’s minor mode gives the matter the seriousness it deserves, and the climbing sequences in the opening of the B section,

which momentarily depart from the minor mode, allow us to sing the repeated texts without flagging in energy. The best hymn tune here will be the one that bears, and does not sap, the vehemence with which we assert: “none but Jesus, none but Jesus, none but Jesus can do helpless sinners good.”

BRYN CALFARIA

CAERSALEM

BEACH SPRING

NOTE

[1] The most commonly used tune today, RESTORATION/ARISE, does not fit the pattern at all. We cannot recommend it because its rhythm requires the omission of the most important part of the stanza. Instead, there is an incongruous chorus.