For All the Saints

Saints’-Day hymn

William Walsham How, 1864

Addressed to Christ and, indirectly, to one another in st. 4–6

| For all the saints who from their labors rest, | Ps. 148:14; Rev. 14:13 |

| who thee by faith before the world confessed, | Rom. 10:9; 1 Tim. 6:12b; Heb. 11; 1 John 4:15 |

| thy name, O Jesus, be forever blest. | Ps. 72:19 |

| Alleluia! | |

| Thou wast their rock, their fortress, and their might; | Ps. 18:1-2 Matt. 7:24; 2 Tim. 2:1 |

| thou, Lord, their Captain in the well-fought fight; | Josh. 5:14; 1 Tim. 6:12a; 2 Tim. 4:7; Heb. 2:10 KJV |

| thou, in the darkness drear, their one true light. | John 1:5; 8:12; 1 John 2:8 |

| Alleluia! | |

| Oh, may thy soldiers faithful, true, and bold, | Prov. 28:1; 2 Tim. 2:3 |

| fight as the saints who nobly fought of old, | Heb. 12:1 |

| and win with them the victor’s crown of gold. | 2 Tim. 4:8; James 1:12; Rev. 2:10 |

| Alleluia! | |

| The golden evening brightens in the west; | Matt. 20:8 |

| soon, soon to faithful warriors comes their rest; | Rev. 14:13 |

| sweet is the calm of paradise the blest. | Luke 16:25 |

| Alleluia! | |

| But lo! there breaks a yet more glorious day; | Is. 60:19–20 |

| the saints triumphant rise in bright array; | 1 Cor. 15:43; Rev. 19:8 |

| the King of glory passes on his way. | Ps. 24:7–10; Rev. 19:11–16 |

| Alleluia! | |

| From earth’s wide bounds, from ocean’s farthest coast, | Is. 42:10; Jer. 31:8; Rev. 20:13 |

| through gates of pearl streams in the countless host, | Rev. 7:9; 21:21 |

| singing to Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. | |

| Alleluia! | Rev. 19:1–6 |

When Paul exhorts us to sing, he makes no promise that this will be an easy affair. Obedience to this command, as all commands, comes in the face of obstacles not only spiritual (for who is naturally inclined to obey?) but also, and more importantly here, mechanical. Part of the goal of this web site is to explain why the mechanism of strophic hymnody, as invented and executed by the reformers, overcomes some—perhaps never all—of the mechanical hurdles we face when we try to obey Paul’s commands. Not all hymns overcome these hurdles with equal success. For some, the poetry is still impassably dense, even for the most engaged but unliterary of congregants. For others, the tune is more athletic than the voice even of the most enthusiastic of amateur singers. In the case of this hymn, both poetic density and melodic athleticism meet, along with another difficulty—irregularity of syllable-placement, to make for what must be the most difficult of all the hymns discussed here. We included it, nevertheless, for three reasons. First of all, very difficult hymns can be sung well by congregations, even congregations of weak singers, when they have come to know those hymns intimately. Second, the text of this hymn enables congregations to do something that they regularly find necessary: to offer thanks for the lives of departed saints. No other hymn in the Trinity Hymnal does this, and this hymn does it with poetic beauty, biblical density, and theological accuracy. Third, the exertions required by the text and tune make their description of the perseverance of the saints more vivid. By contrast, what would it communicate if we sang about the “well-fought fight” or the “countless host” in a relaxed, comfortable way? Sometimes it’s right for worship to be tiring.

Avoiding the misdirected praise of older texts written for All-Saints Day, this hymn’s first stanza blesses not the saints, but Jesus, who is the true object of our praise when we consider the lives of “those who have fallen asleep.” The sense of the first stanza is hard to obtain because the extended prepositional phrase which opens it comes before the sentence’s subject and verb. The inversion is justifiable, however, for the way it focuses our attention on the very right, but very surprising, Christ-centeredness of the stanza. It leads with “for all the saints . . .” but it isn’t them we praise. In what other hymn do we praise Jesus for the rest obtained and the confession made by the many Christian souls that have gone before us?

The reason why we should praise Jesus for the safety of these souls is explored in the second stanza. Christ’s relation to those saints is enumerated through a list of familiar titles given to him by Scripture. Here we must note briefly a change in the poem’s rhythm that will become more important when we examine the tune. The poem is in regular iambics (following the rhythmic pattern da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM) except in a handful of moments, two of which are in this stanza. Both phrases that begin with the word “thou” are rhythmically ambiguous but suggest an initial trochee for most English speakers.

/ x

thou, Lord . . .

The iambics of the preceding lines prepare us to hear “thou” without an accent, but when we arrive on it, we give it one. Poetically, the change is important because of the emphasis it puts on our address to God.

One reason we sing about the saints who have gone on before us is to celebrate Christ’s goodness to them. Another is to encourage each other through their example. The third stanza asks Christ to make us as faithful as those who have fought and won. Notice here a delightful shift in rhythm. Our iambic metronome has been ticking away for a whole line and then we start the second line with the word “fight,” which must, in spite of expectations, be accented to form another trochee. Here there is no ambiguity and the forceful pounce on the word “fight” brings new vigor to the word itself.

Part of the encouragement we gain when we consider foregone saints comes from the hope we have of soon sharing their rest. The fourth stanza pictures this rest as a sunset that, curiously, “brightens.” The paradox is beautiful and will carry us into the imagery of the fifth stanza, where a contrast between sunset and daybreak is a metaphor for the contrast between our intermediate state (between death and Christ’s return) and our final, resurrected state. We meet more trochees to start the second and third lines of stanza 4, for an emphasis first on the imminence of our rest and second on its sweetness.

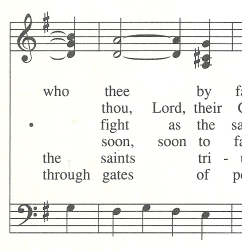

So, what is a tune to do with these five instances where the poem shifts, with beautiful effect, from strictly iambic rhythm to initial trochees? When the question is asked of most hymn tunes, they reply, “nothing at all—I’m a strophic form and must have the same rhythm for each stanza, however the poet may muck about with his rhythm.” This tune, SINE NOMINE, was written by the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams as part of his development of the English Hymnal—among the most celebrated of all hymnals. Vaughan Williams appreciated the importance of the poem’s original rhythm and consequently sets it to a tune that is not, strictly speaking, strophic. Its rhythm does change from stanza to stanza, to allow the unexpected first syllables of each trochee to fall on strong beats in the music. Good hymnal editors usually set this hymn so that each of these irregular moments falls at the left margin of the page, where the eye begins to read each new line of music. In this snapshot from the Trinity Hymnal, notice the empty space to the left in stanzas 2, 3, and 4.

Explaining to a congregation this irregularity, and reminding them simply to wait a moment at each of those spots where we expect a word but haven’t one, will go a long way to making this very difficult hymn a very rewarding one.

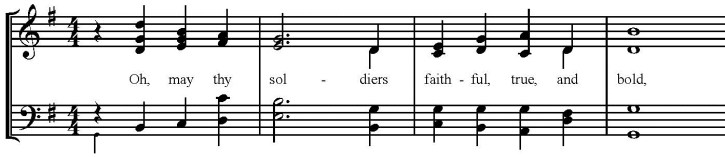

The accompanist can help, too. Using a thinner texture (with a bass that doesn’t move on the long syllables) for stanzas 3–4 can bring out the text’s reflective side and invite softer singing for a spell, leaving congregants with enough stamina for the sublime closing stanzas. The thinner texture could be something like:

Playing an instrumental bridge between the end of stanza 5 and the beginning of stanza 6 can give congregants a chance to catch their breath. (Just displace the last chord with an instrumental restatement of both alleluias.)

SINE NOMINE