For the Beauty of the Earth

Folliott S. Pierpoint, 1864

Addressed to God

| For the beauty of the earth, | Eccl. 3:11 |

| for the glory of the skies, | Ps. 19:1; 69:34 |

| for the love which from our birth | Ps. 22:10; 23:6; 71:6; Matt. 5:45 |

| over and around us lies, | Ps. 5:11; 119:64; Prov. 3:3 |

| Lord of all, to thee we raise | |

| this our hymn of grateful praise. | Ps. 68:4; 103:2 |

| For the beauty of each hour | |

| of the day and of the night, | Ps. 19:2; 42:8; Jer. 33:25 |

| hill and vale, and tree and flow’r, | Gen. 1:12; Ps. 121:1; Is. 63:14 |

| sun and moon and stars of light, | Ps. 148:3; Jer. 31:35 |

| Lord of all, to thee we raise | |

| this our hymn of grateful praise. | |

| For the joy of ear and eye, | Prov. 20:12; Matt. 13:16; Luke 18:43 |

| for the heart and mind’s delight, | Ps. 111:2 |

| for the mystic harmony | |

| linking sense to sound and sight, | 1 Sam. 24:11; John 20:27 |

| Lord of all, to thee we raise | |

| this our hymn of grateful praise. | |

| For the joy of human love, | Song 1:4; 4:10; Phil. 1:3–9 |

| brother, sister, parent, child, | Ps. 127:3; Prov. 17:17; 1 John 3:14 |

| friends on earth and friends above, | 2 Sam. 1:26 |

| for all gentle thoughts and mild, | Phil 4:8; 1 Tim. 2:8 |

| Lord of all, to thee we raise | |

| this our hymn of grateful praise. | |

| For each perfect gift of thine | James 1:17 |

| to our race so freely giv’n, | 1 Tim. 6:17 |

| graces human and divine, | |

| flow’rs of earth and buds of heav’n, | 1 Cor. 13:12 |

| Lord of all, to thee we raise | |

| this our hymn of grateful praise. |

Ask Christians why they praise God and most will probably answer with the gospel message—that God sent his son Jesus Christ to reconcile us to himself. This is a good answer and perhaps the best one. No sooner is it said, however, than it prompts a number of other questions. All of them could be summarized thus: what is God that you would wish to be reconciled to him? When we say that we praise God because he reconciled us to himself, what we really mean is that God is great and good, and that we praise him because he reconciled us to such a great and good person as himself. But how do we know of his greatness and goodness? Sure, we know God through the Scriptures, but what sense would even God’s holy Word make to us had we not his works of creation and providence? Had we never seen the heavens, we could hardly believe that they declare God’s glory (Ps. 19). Had we never seen a sheep, we could hardly imagine how like them we are, or how like a good shepherd God is (Ps. 23). And, had God never brought us out of a dire situation or led us into one for the purposes of testing, probably a third of Scripture’s meaning would be lost on us. It makes sense, then, for a meaningful part of a congregation’s song to be given over to praising God for his works of creation and providence. One may rightly ask, “were we not commanded to let the word of Christ, not the works of Christ, dwell richly in us?” Yes, but the word of Christ is our model for praising God for his works, beginning in Genesis 1 and continuing until sun and moon will shine no more. The hymn printed above is little more than a partial list of the works of God’s creation and providence, yet it is a wise selection arranged in a memorable poetic form with a refrain that helps us rightly direct our delights to God.

The hymn begins and ends with a comprehensive pairing (“earth” and “skies”; “flow’rs of earth and buds of heav’n”) and a definition of that pairing (“the love which . . . over and around us lies”; “each perfect gift of thine”). Beauty is thus identified as an emblem of God’s love for us, a love that began even at our sinful birth. It is identified as a perfect gift given to mankind. And it is. But beauty is more than this. It is heaven beginning to spring up on earth. It is a foretaste of glory divine.

In the stanzas in between, we chronicle to each other the many things that show us how God loves us and reveals his heaven to us in this life—in the passage of time, in landscape and botany, in the celestial bodies, in the senses, intellect, and the way they work together, in our own mortal loves. This last one is a good one to end on, for it recalls the “love . . . from our birth” of the first stanza and prepares us for the final stanza’s insistence that all these beauties are part of a love relationship more than mortal.

If the pleasures of this life are so important, why doesn’t the church sing about them more often? The answer is abundantly clear in Scripture. We are tempted to worship and serve the creature rather than the creator (Rom. 1:25). Much of the near pantheism of some forms of nineteenth-century Christianity gives witness to what happens if we place a wrong emphasis on this world. This hymn’s refrain, and the very grammar that serves it, is the expedient we need to avoid this error. For each stanza is really no more than a prepositional phrase that attends the refrain.

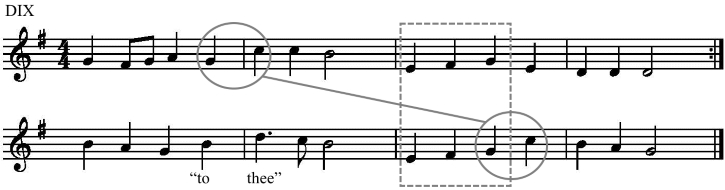

The hymn-tune DIX serves this grammar admirably. The tune has two musical lines, the first of which is repeated to set the text of each stanza, and the second of which sets the refrain. The first is tentative—even furtive. It’s first leap (from the last syllable of ‘beauty” to “of”) seems uncomfortable because it is a leap to a note that really wants to resolve down (as it does on “earth”). There’s nothing easy about jumping up to a platform that is falling. After this clumsy acrobatics, the first line ends by muttering around low “sol” (“of the skies”). The refrain, where we finally name the object of our praise, offers satisfaction to all this. It begins on “mi,” which was the note of arrival for the first line’s first phrase. That is, the second line of music begins at the first line’s halfway mark. And after an initial descent on “Lord of all,” we cover altitude more quickly than we’ve yet done and finally reach high “sol” on the word “thee,” here referring to God. All of the hymn’s observations are directed, not to the objects of creation and providence, but to God himself. The first three notes of the second phrase of the first line return at the corresponding place in the second line to be combined now with the uncomfortable leap from the first phrase—only now the leap occurs where it seems to belong, on the weakest beat of the measure, and it resolves decisively with a march down the scale to “do” on the word “grateful.”