God Moves in a Mysterious Way

Light Shining Out of Darkness

William Cowper, 1774

Addressed to one another

| God moves in a mysterious way | Job 9:10; Is. 55:8; Rom. 11:33 |

| his wonders to perform; | |

| he plants his footsteps in the sea, | Job 38:16; Ps. 77:19; Matt. 14:25; Rev. 10:2 |

| and rides upon the storm. | Ps. 18:10; 104:3; Is. 19:1; 66:15; Nah. 1:3 |

| Deep in unfathomable mines | Job 28; Rom. 11:33 |

| of never-failing skill | |

| he treasures up his bright designs, | Dan. 2:22 |

| and works his sovereign will. | |

| Ye fearful saints, fresh courage take; | Deut. 1:28–29; Ps. 31:13–15; Is. 8:12; Matt. 6:25 |

| the clouds ye so much dread | Gen. 9:12–16; 45:5; Ex. 20:18–20 |

| are big with mercy, and shall break | Zech. 10:1 |

| in blessings on your head. | Deut. 23:5; Ezek. 34:26; Rom. 8:28 |

| Judge not the Lord by feeble sense, | Job 40:7–9; Prov. 3:5 |

| but trust him for his grace; | Ps. 23:6 |

| behind a frowning providence | Gen. 50:19–20 |

| he hides a smiling face. | Job 10:12–13; Is. 45:15; 54:8 |

| His purposes will ripen fast, | Ps. 30:5 |

| unfolding ev’ry hour; | Mark 4:27 |

| the bud may have a bitter taste, | Is. 38:17 |

| but sweet will be the flow’r. | |

| Blind unbelief is sure to err, | Rom. 8:7; 2 Cor. 4:4 |

| and scan his work in vain; | Rom. 1:20–21 |

| God is his own interpreter, | Gen. 40:8; 1 Cor. 2:10 |

| and he will make it plain. | Matt. 10:26; John 13:7; Eph. 1:9 |

Detractors from Reformed Evangelicalism often remark that the Reformation took the mystery out of Christianity. Yet William Cowper, a thoroughgoing Calvinist, here notes that among the most mysterious aspects of the faith is precisely that thing which makes Reformation thought so distinctive. Most rational minds can assent to the virgin birth or the miracles of Christ, if they begin with the right premises. A supernatural salvation requires a supernatural savior. But when we are asked in Scripture, in plain prose, to count trials a joy and to believe all things work together for good we are asked to believe a great mystery. A hymn to handle such mystery must insist on the only possible answer to the riddle of theodicy—“God is his own interpreter, and he will make it plain.”

Knowing how unhelpful it is to speak vaguely about mystery, Cowper defines his very clearly in the first sentence. It’s not so much that God is mysterious in his person or in his works, but he is so in the ways by which he accomplishes those works. The unusual word order underscores this idea. (Consider the subtle difference if the words are ordered like normal prose: “God performs his wonders in a mysterious way.” The crucial word “moves” is missing. In Cowper’s version, “perform” carries extra weight because of its role in the stanza and rhyme.) The second sentence may seem unrelated—a generic description of God’s omnipotence in Old-Testament imagery of sea and storm. But Cowper has thereby turned us, reading on this side of the New Testament, toward Christ’s mysterious walking on water. His person is not mysterious (“Truly you are the Son of God,” the disciples said), nor is it mysterious that he would reveal himself in might, but that he would do so by asserting his sovereignty over nature (not Rome) before a mere audience of twelve (not the masses) was indeed mysterious. Yet now, living after his resurrection, we understand his reasons well enough. He has made it plain.

The second stanza evokes imagery of gems or precious metals with its illustration of mines and “bright designs.” Note, however, that it is the skill of God that is the jewel under discussion and the treasures are his designs. Precious things are often hidden, so that they are accessible only to the ones to whom they belong. Returning to the storm imagery in the third stanza, Cowper uses its inherent double nature—storms are indeed dreadful, but when in need of rain, they are a blessing. We won’t know until it arrives whether the cloud will bring crop-destroying hail or blessed rain but we must trust that it will be the latter. Indeed, trust is the very next idea to be involved. The picture of God hiding is not easily reconciled with the revealing God of Scripture until we consider the many illustrations that describe him as a father. How often have parents swallowed down a smile in order to turn firm and apply discipline to a child who needed it. The smile remains in the heart, whatever appearance in the face. And it isn’t a smile that laughs at the sins because they are small ones. It is a smile that loves in spite of them.

The last stanza makes Cowper’s point plain even as it promises that God will make his so. That the unbeliever scans God’s work is evident because of the error that comes and the vanity of the inquiry. Contrasting unbelief, however, is not belief directly, but God himself, whose interpretation is set against the scanning look of the unbeliever.

Poetic elements do their part to describe this progression from “mysterious” (first line) to “plain” (last word). For an example of meaningful rhyme consider the last stanza, which contrasts the keywords “vain” and “plain.” On one hand, it’s a contrast between the futility of the unbeliever’s scanning and the clarity of God’s revelation. On the other hand, it’s also a contrast between the pride, or vanity, of unbelief and the unpretentious simplicity of what God reveals. For an example of meaningful rhythm, read aloud the first two lines of stanza 2:

Unfathomableness coincides with rhythmic irregularity; God’s skill, with a return to correct meter. For an example of meaningful alliteration, note how the first stanza links “moves” with “mysterious,” “way” with “wonders,” “perform” with “plants,” and “[my]-sterious” with “[foot]-steps” and “storm.” In stanza 3 “big” and “blessings” frame “break,” the explosive sounds of which onomatopoetically mark the poem’s abrupt change from dread to blessing.

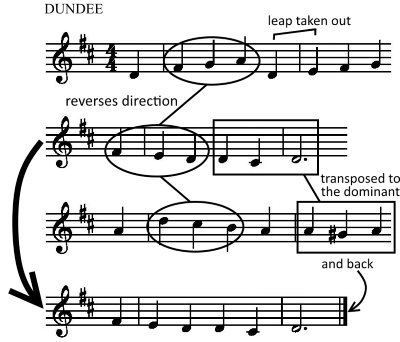

DUNDEE may seem like an odd fit here because, however good the tune, there’s absolutely nothing mysterious about it. It opens with an ascending gesture that repeats with the leap taken out, and the second line of the stanza is essentially a cadence back on “do”—the note where we started. The second and third lines reverse the direction of the first’s stepwise motion.

The fourth line simply reiterates the cadence on “do.” But perhaps this elegant, plain-speaking melody is exactly right. The hymn’s theme is not mystery in itself but rather providence, and DUNDEE does well to express both our humility before providence and the plainness of the mystery when revealed.[1]

NOTE

[1] Plain, but not boring. The high D in the third line of the stanza towers above the rest of the tune in a climax perfect for “he plants his footsteps” in stanza 1 and “are big with mercy” in stanza 3.