Good Christian Men, Rejoice

John Mason Neale, 1853

Addressed to one another

| Good Christian men, rejoice, | Ps. 32:11; 53:6; Zeph. 3:14; Zech. 2:10 |

| with heart and soul and voice; | |

| give ye heed to what we say: | Col. 3:16 |

| Jesus Christ is born today; | Luke 2:11 |

| earth and heav’n before him bow, | Matt. 28:18; Luke 2:16–20; Phil. 2:10 |

| and he is in the manger now. | |

| Christ is born today! | |

| Christ is born today! | |

| Good Christian men, rejoice, | |

| with heart and soul and voice; | |

| now ye hear of endless bliss: | Is. 65:18–19 |

| Jesus Christ was born for this! | Luke 2:11 |

| He hath opened heaven’s door, | John 1:51; Rev. 2:7 |

| and man is blessèd evermore. | |

| Christ was born for this! | John 3:17 |

| Christ was born for this! | |

| Good Christian men, rejoice, | |

| with heart and soul and voice; | |

| now ye need not fear the grave: | 1 Cor. 15:55; 1 Thess. 4:14 |

| Jesus Christ was born to save! | Matt. 1:21 |

| Calls you one and calls you all | Matt. 11:28; Mark 1:15; Luke 5:32 |

| to gain his everlasting hall. | John 14:3 |

| Christ was born to save! | John 3:16 |

| Christ was born to save! |

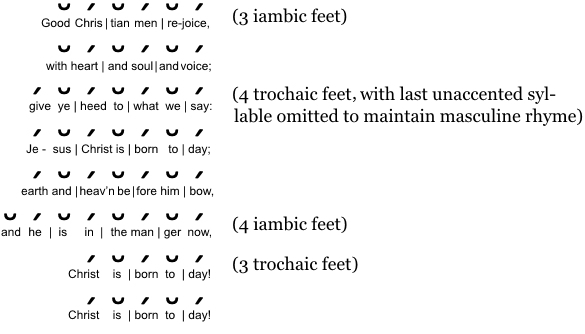

The medieval carol from which John Mason Neale’s hymn originated is called “macaronic” because it playfully jumbles two languages (Latin and German). Neale’s hymn is so far removed in content from this carol that we cannot call it a translation, yet it does share close ties to the carol’s poetic sensibility. Neale’s hymn is direct, exuberant, and, just as the medieval poem fluctuates between two languages, Neale’s hymn fluctuates between iambic rhythm and trochaic rhythm, and between repeated lines and non-repeated lines, to give us the sense (suggested in the medieval carol, too) of many voices speaking at once. Each of the three stanzas begins the same way, with a refrain. Each ends with an altered version of the stanza’s respective fourth line—in each case a summary of the middle four lines—sung twice.

Lest the reader think the middle four lines of the first stanza are mere platitude, consider how their ideas relate. “Give ye heed to what we say”—that is, let the full weight of the next idea settle into your mind—“Jesus Christ is born today.” The next couplet makes it clear that the emphasis lies less on “today” and more on the incarnation itself—heaven and earth bow before the infant Christ in a feeding trough. One thinks of Hugo van der Goes’s Portinari Altarpiece with a tiny infant Christ surrounded by larger-than-life worshipping hosts. The second stanza’s interior couplets explain how the Advent relates to us: it brings us bliss, it makes heaven available, and it brings blessing to all humanity. The last stanza’s interior couplets are more explicit about that blessing—we needn’t fear death, for the gospel call is extended to us. We finish with the delightfully medieval image of an everlasting hall. (In Germanic mythology, by contrast, it is prophesied that the hall of the gods—Valhalla—will burn with the rest of the world when the end comes.)

The refrain that recurs at the beginning of every stanza is solidly iambic. The non-repeating verse that follows in line 3 begins with an additional, stressed syllable; so, compared to the refrain, the developmental lines 3–5 have an extra foot and the opposite rhythm (trochaic instead of iambic). Line 6 adds yet another syllable to the beginning of the line, this time unstressed, inverting the rhythm once again as a jarring predecessor to the final lines. These are solidly trochaic and introduce a different kind of repetition: whereas the opening refrain of lines 1–2 repeat from stanza to stanza, line 7 repeats within the stanza, in line 8. So, repetition of one kind, in iambic rhythms, gives way to development in a mixture of rhythms and, finally, to another kind of repetition, in trochaic rhythms, giving the reader and singer a sense of multiple voices. And yet holding all this antiphony together is a clear structure of adding one syllable at a time until we reach the climactic line 6 with its eight syllables (“and he is in the manger now”). Then we cut to the shortest lines of all for the exuberant quasi-refrain at the end.

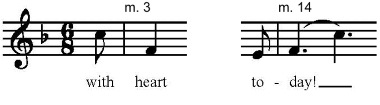

The success of the medieval text cannot be separated from the merits of its traditional tune, IN DULCI JUBILO. Typical of medieval carols, it has a distinctive rhythm in what we would now call a compound meter (the beat is subdivided in three rather than in two), which skips along in the most dance-like motion of any tune studied on this web site.[1] The melisma in measures 2 and 4 springs for “rejoice”; it jubilates for “voice.”

It is tempting to stamp one’s foot on the downbeat of lines 3 and 5 (that is, of measures 5 and 9). The leap at the beginning of measure 3, from C to F, prepares us for the leap from F to C at the end.

The three parts of the tune work well with Neale’s three-part structure (refrain, two couplets, refrain-like repeated line), even as they introduce new layers to its multi-phonic character: the first kind of repetition in the text (lines 1–2 of the stanza, which repeat across stanzas) is marked musically by immediate repetition of a short gesture only two measures long. The developmental, interior quatrain is set to the repetition of a longer gesture, four measures long. And the quasi-refrain at the end has no repetition at all. So, whereas the text begins with repetition across stanzas and concludes with repetion within the stanza, the tune does precisely the opposite: it begins with repetition within the stanza and concludes with music that doesn’t repeat until the tune itself is sung again for the next stanza.

Described analytically like this, the ever-changing rhythms and patterns of textual and musical repetition seem confusing. But, in practice, as we have shown, there is a clear train of thought in the words—from incarnation to gospel—and an organizing structure in the poetry and the way it relates to the tune. The many “voices” are harmonized, to the delight of congregations past, present, and future.

NOTE

[1] Many medieval carols were associated with dancing. The earliest surviving reference to “In dulci jubilo” is from the early fourteenth-century mystic Heinrich Suso, who was invited in a vision to dance with angels as they sang this song. “Indeed, in many Lutheran parishes in the late sixteenth century it was still customary for the children to dance in the sanctuary, in front of a crib placed before the altar, while ‘In dulci jubilo’ was sung.” [Alan Luff and Robin A. Leaver, “Good Christian friends, rejoice,” in Companion to The Hymnal 1982, vol. 3A (1994) pages 215–16, citing H. Kätzel’s Musikpflege und Musikerziehung im Reformationsjahrhundert, dargestellt am Beispiel der Stadt Hof (1957), 19 and 103.