Hark! the Voice of Jesus Crying

Stanzas 1, 2, and 4, Daniel March, 1868

Addressed to one another

| Hark! the voice of Jesus crying, | |

| “Who will go and work today? | Is. 6:8a; Matt. 28:19 |

| Fields are white, and harvests waiting; | John 4:35; Rom. 1:13 |

| who will bear the sheaves away?” | Luke 10:2 |

| Loud and long the Master calleth, | Matt. 20:1 |

| rich reward he offers free; | Mark 10:29–30; 1 Cor. 3:14 |

| who will answer, gladly saying, | |

| “Here am I; send me, send me.” | Is. 6:8b |

| If you cannot cross the ocean, | 1 Cor. 12:6; Rom. 15:22; 1 Thess. 2:18 |

| and the heathen lands explore, | |

| you can find the heathen nearer, | Acts 17:16–18 |

| you can help them at your door. | |

| If you cannot give your thousands, | |

| you can give the widow’s mite; | Mark 12:41–44 |

| and the least you give for Jesus | 2 Cor. 8:12 |

| will be precious in his sight. | |

| If you cannot be a watchman, | Is. 52:8; Jer. 31:6; Ezek. 33:7 |

| standing high on Zion’s wall, | |

| pointing out the path to heaven, | John 14:6 |

| off’ring life and peace to all, | Rom. 8:6 |

| with your pray’rs and with your bounties | Matt. 7:7; Phil 4:6; 2 Cor. 9:7 |

| you can do what God demands; | Luke 12:48 |

| you can be like faithful Aaron, | |

| holding up the prophet’s hands. | Ex. 17:12 |

| Let none hear you idly saying, | |

| “There is nothing I can do,” | Matt. 25:24–25 |

| while the sons of men are dying, | Rom. 10:13–15 |

| and the Master calls for you: | John 17:18 |

| take the task he gives you gladly, | 2 Cor. 12:15 |

| let his work your pleasure be; | Acts 20:35 |

| answer quickly when he calleth, | |

| “Here am I; send me, send me.” |

Some of Scripture’s great calls to evangelism come from the very mouth of God. One thinks of Isaiah 6 and Matthew 28. But others come by the example of the prophets and apostles who in their witness serve as models for all believers. In this hymn, we get both types of calls to evangelism, along with a dose of admonition to keep us from shirking our duties.

The hymn’s first line bids us attend to the words of Christ—perhaps the most fitting thing that a hymn can do. His words here are a pastiche from the gospels, where we find the unreached souls of the world described as a harvest. The first stanza ends with the rhetorical question: “who will answer.” We are meant to then ask ourselves if the answer is, “I.” Anticipating our reluctance (and even Moses had reluctance) the poem devotes two stanzas to explaining away our excuses.

The first excuse comes from the various encumbrances on us which prohibit a lengthy journey. Many have been legitimately kept from the foreign mission field by the expectations of the fifth commandment. Others have physical debilities which keep them at home. But here we are reminded that we can find “the heathen nearer.” The second excuse comes to the minds of those whose vocational gifts do not draw them to the mission field. Yet such Christians may yet have vocational gifts which afford them “bounties” that could be given for mission work. But perhaps such Christians as these may not feel their bounties to be very bounteous. The hymn reminds them that even the least amount is precious to Jesus.

The third stanza addresses not so much an excuse as a misapprehension. The work of gospel ministry is so beautiful, so lofty (lines 1–4), that ordinary believers may humbly balk at the thought that they might have a part to play in it. Yet everyone can pray and all who have abundant provision can give some of it in support of mission work. The image of Aaron and Hur holding up Moses’s arms over the armies of Israel and Amalek may seem hyperbole, but the onslaught of the hosts of hell upon human souls is far fiercer than that of the Amalekites, the strain of preaching the gospel to the heathen is far greater than that of gravity against one’s arms, and the stakes of the battle are equally—indeed eternally—consequential. Shirking is therefore inexcusable, even if we are only called to aid God’s messengers.

Having heard the call of Jesus and had our concerns answered, we hear the call to missions again in the last stanza, in words of admonition that we give to one another to arm us against cowardice and laziness.

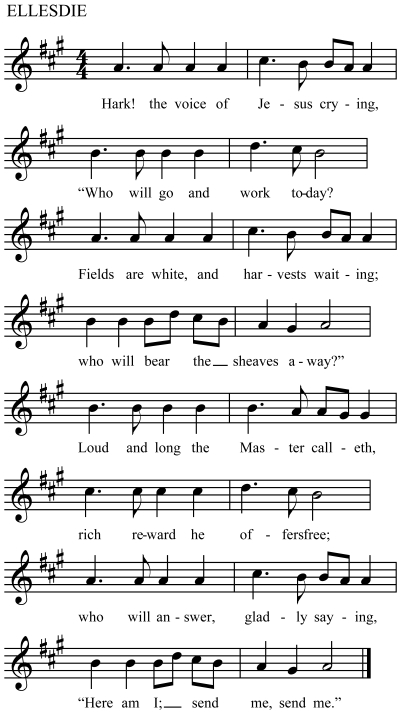

The poem’s unfailing trochees and unflagging alternating rhyme are as insistent as its message. So too is the tune ELLESDIE to which this text is often set. It has by far the highest tessitura (where in its range the voice predominantly lies) of any tune studied on this website. Fully 95% of the notes are an A or higher, which is fitting for a hymn about cries and calls. Of the tune’s sixteen measures, twelve begin with a dotted quarter followed by an eighth. Six of the measures are made up of one note merely repeated four times. In fact, there are only eight measures of music in the whole tune, which are reused to create the coherent whole. Yet for all the repetition, the tune is not dull or unmemorable.

Its first half is complete, with lines 3–4 of the stanza (measures 5–8) opening as a repeat of lines 1–2, but closing with two new measures of music to draw a satisfactory conclusion. The second half of the tune opens in measure 9 with the same repeated notes and dotted rhythm as the first half, but now transposed up a step. Yet even this is not new, for we have heard this same note repeated thus before in the third measure of the tune. Two measures of new music follow, but then we return again to earlier music—the music of measure 4—in measure 12. This kind of rearranging makes new from old and allows for an easily mastered but unforgettable tune. The same thing that makes it easily mastered, however, also makes it insistent, and we notice that most when we come to lines 7–8 of the stanza, which are just a reiteration of lines 3–4. If they were conclusive then, they are more so now after the ascending repetition of lines 5–6. The formulaic last measure, which arrives on the tonic note on the downbeat and then returns to it on the third beat, works perfectly with the last four words of stanzas 1 and 4: “send me, send me.”