Holy God, We Praise Your Name

Clarence A. Walworth, 1853; based on the Te Deum (4th or 5th c.)

Addressed to God

| Holy God, we praise your name; | 1 Chron. 29:13 |

| Lord of all, we bow before you; | Ps. 95:6 |

| all on earth your scepter claim, | Ps. 47; Is. 45:23 |

| all in heav’n above adore you. | Neh. 9:6 |

| Infinite your vast domain, | 1 Chron. 29:12; Ps. 103:19; 119:91 |

| everlasting is your reign. | Ex. 15:18; Ps. 45:6; 146:10; Dan. 4:34 |

| Hark, the loud celestial hymn | Is. 6:1–4; Rev. 4:6–8 |

| angel choirs above are raising; | |

| cherubim and seraphim | |

| in unceasing chorus praising, | |

| fill the heav’ns with sweet accord: | |

| “Holy, holy, holy Lord.” | |

| Lo! the apostolic train | Rom. 1:5; Rev. 4:9–10 |

| join your sacred name to hallow; | |

| prophets swell the glad refrain, | Is. 25:1; Luke 13:28; Acts 10:43; Rev. 18:20 |

| and the white-robed martyrs follow; | Acts 7:56; Rev. 6:9–11; 20:4–6 |

| and from morn to set of sun, | Ps. 113:3 |

| through the church the song goes on. | Ps. 89:1; Eph. 2:19–21 |

| Holy Father, Holy Son, | |

| Holy Spirit, Three we name you; | Matt. 28:19; Rom. 8; 2 Cor. 13:14; Eph. 1 |

| while in essence only One, | Deut. 6:4; John 10:30; Rom. 3:30 |

| undivided God we claim you, | John 14:10 |

| and adoring bend the knee, | |

| while we sing this mystery. |

What does it mean to praise God’s name? It is unlawful to worship anything other than God, no matter how directly it, like the bronze serpent made by Moses (2 Kings 18:4), may point to him. Yet the Bible frequently describes the faithful as praising God’s name (Ps. 148:13), giving thanks to his name (1 Chron. 16:35), singing to his name (Ps. 135:3), blessing his name (Neh. 9:5), glorifying his name (Rev. 15:4), and fearing his name (Deut. 28:58). If, then, the praise of his name is not forbidden by God’s word but actually required by it, which name do we praise? Elohim? Yahweh? Adonai? Theos? Kurios? Their English equivalents? The Bible contains many names for God, but sometimes it refers to the name of God, in the singular, as if there were only one. We are not to take it in vain (Ex. 20:7). Jesus taught his disciples to pray that God would hallow it (Matt. 6:9). And he himself prayed, “Father, glorify your name” (John 12:28). In these and many other instances, God talks as if he has one name.

The name of God is everything he has revealed to us about himself. It is all that we know, and can know, about him. In this sense, to worship his name is to worship him—and to worship him exactly as he would have us to. The doctrine of the names of God harmonizes the unknowableness of God with his knowableness: humans cannot know the incomprehensible God as he is in himself, but we can know him as he has shown himself. Because he has graciously manifested himself to us, we can call him by name, we can call upon his name (that is, not just his proper names, but his attributes and persons as well), and therefore his names ought to be consecrated and glorified.

The hymn before us does this very well. It does not attempt a systematic catalog of God’s names, which would be futile within the scope of a congregational song. But it begins with the simplest and earliest that God made known: God (Elohim) and Lord (Adonai). He is the powerful ruler whose sovereignty is boundless in space (“infinite your vast domain”) and time (“everlasting is your reign”). Then, in stanzas 2 and 3, the communion of angels and saints quotes Isaiah 6:3 to acclaim the covenantal name LORD (Yahweh), by which he attests that he is the God of his people, that is, the God who in steadfast love takes the very singers listed in stanza 3 to be his own. That Walworth’s hymn is based on an ancient, widespread, and frequently-sung Latin hymn can make us even more conscious of the communio sanctorum. Finally, “Holy God, We Praise Your Name” culminates at the beginning of stanza 4 with the name Father (Pater)—“the common name of God in the New Testament,” as Herman Bavinck called it. The closing paragraph of his treatment of the names of God in Reformed Dogmatics is so relevant to the meaning of this hymn that we reproduce it in full.

The name YHWH is inadequately conveyed by Lord (κυριος) and is, as it were, supplemented by the name “Father.” This name is the supreme revelation of God. God is not only the Creator, the Almighty, the Faithful One, the King and Lord; he is also the Father of his people. The theocratic kingdom known in Israel passes into a kingdom of the Father who is in heaven. Its subjects are at the same time children; its citizens are members of the family. Both law and love, the state and the family, are completely realized in the New Testament relation of God to his people. Here we find perfect kingship, for here is a king who is simultaneously a Father who does not subdue his subjects by force but who himself creates and preserves his subjects. As children, they are born of him; they bear his image; they are his family. According to the New Testament, this relation has been made possible by Christ, who is the true, only-begotten, and beloved Son of the Father. And believers obtain adoption as children and also become conscious of it by the agency of the Holy Spirit (John 3:5, 8; Rom. 8:15f.). God has most abundantly revealed himself in the name “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.” The fullness that from the beginning inhered in the name Elohim has gradually unfolded and become most fully and splendidly manifest in the trinitatian name of God. (Volume 2, subparagraph 191, translated by John Vriend [Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2004], page 147)

The structure of “Holy God, We Praise Your Name” follows the pattern of the progressive revelation of God’s names, so that the sequence of its topics (God’s sovereignty, the church universal’s worship, doctrine of the Trinity) makes perfect sense. The unifying motif of holiness helps, too. By calling God (Elohim) “holy,” the opening line prepares us for the angels’ chorus, “holy, holy, holy LORD,” in stanza 2, even as the threefold repetition of “holy” there prepares us for the Trinitarian last stanza: “Holy Father, Holy Son, Holy Spirit.”

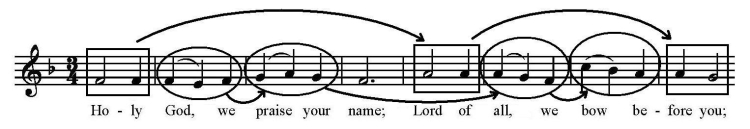

There’s something rather satisfying in singing about the Holy Trinity (or, for that matter, the Sanctus text) in triple meter. Every measure has three pulses, or beats. In GROSSER GOTT, WIR LOBEN DICH this surface triplicity agrees with the overall form of the tune, which unfolds in the three sections of a bar-form. The three pulses of the measure are grouped in three ways (see musical example). In the first measure we sing a long note and a short note. When this gesture returns at the beginning of line 2 (“Lord of” in stanza 1), we sing it on a higher pitch; music theorists would say that this pitch is a third higher than before. A reversal of this rhythm (from long–short to short–long) punctuates the bar-form in measure 8. The second way in which the three pulses of the measure are grouped also grows in interesting ways. The lower neighbor-note figure in measure 2 reappears in measure 3 on a higher pitch with an upper neighbor-note. By line 2 this figure has developed into a stepwise filling-in of the interval between two notes a third apart—and is immediately repeated (in measure 7) a third higher. The third grouping of the three pulses is simply one long note occurring in measure 4. This is the tune’s bedrock and medial pause for each part of the bar form. So the three groupings of the beats involve one, two, or three notes, each with their distinct office in the tune.

All this music is repeated in the second section of the bar-form (lines 3–4) and then is further developed in the third section (lines 5–6). For example, the harmony of the first and second sections of the bar-form is so basic that the chord in measures 7 and 15, where the melody leaps up, stands out in sharp relief, even though the only striking thing about the chord is that its most important pitch doesn’t occur in the bass. Instead, the bass has what music theorists call the third of the chord. In the third section of the bar-form as harmonized in the Trinity Hymnal, that distinctive apportionment of the chord returns twice in short succession, on the downbeats of measures 18 and 20, to tinge the stirring fifth line of the stanza in its drive to the peak tone at the beginning of line 6. Consider how motivic and harmonic development work together to illuminate, say, the last two lines of stanza 2: “fill the heav’ns with sweet ac-cord: ‘Ho-ly, holy, holy LORD.’”