How Sweet and Awesome Is the Place

Divine Love making a feast, and calling in the guests, Luke 14:17, 22–23

Isaac Watts, 1707

Addressed to one another, then to God

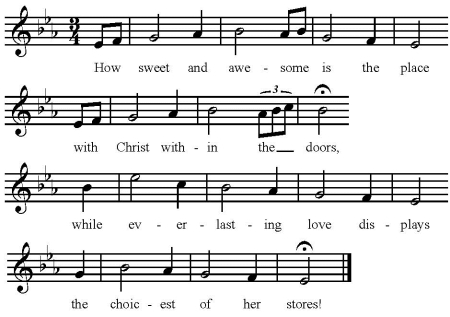

| How sweet and awesome is the place | awful; Luke 10:20; Rom. 11:20 |

| with Christ within the doors, | John 20:19, 26; Rev. 19:9 |

| while everlasting love displays | Ps. 23:5; Is. 55:1–2; Jer. 31:3 |

| the choicest of her stores! | Ps. 107:9; Is. 25:6; John 2:10; 6:51 |

| While all our hearts and all our songs | |

| join to admire the feast, | Ex. 16:32; Ps. 36:8; Jer. 31:12 |

| each of us cries, with thankful tongue, | |

| “Lord, why was I a guest? | Deut. 7:7; 8:17; 9:6; Ezek. 16 |

| “Why was I made to hear your voice, | John 5:25; 10:3 |

| and enter while there’s room, | Luke 14:22 |

| when thousands make a wretched choice, | Jer. 2:5; Luke 14:18–20 |

| and rather starve than come?” | Is. 65:12–13 |

| ’Twas the same love that spread the feast | Eph. 2:4 |

| that sweetly drew us in; | Luke 14:23; John 6:44; Acts 16:14 |

| else we had still refused to taste, | John 5:40; 1 Cor. 2:14 |

| and perished in our sin. | Rom. 6:21 |

| Pity the nations, O our God, | Jon. 4:11 |

| constrain the earth to come; | Ps. 33:8–9; Is. 11:12; Jer. 16:19 |

| send your victorious Word abroad, | Is. 55:11; Matt. 24:14; 2 Thess. 3:1 |

| and bring the strangers home. | Is. 56:6–8; John 11:52; Eph. 2:19 |

| We long to see your churches full, | |

| that all the chosen race | John 10:16; 1 Pet. 2:9 |

| may, with one voice and heart and soul, | John 17:23–24 |

| sing your redeeming grace. | Rom. 15:9; Col. 3:16b |

There aren’t many hymns on the doctrine of election and its corollary, effectual calling. We can only surmise why. Perhaps poets, hymnal editors, and pastors selecting hymns for services, knowing the special prudence and care with which these doctrines must be handled, have judged congregational singing an imprudent way to proclaim them. If so, they are mistaken. The things that are revealed belong to us and to our children (Deut. 29:29). The doctrine of election is supposed to give us matter for praising God (Eph. 1:6) and for consoling one another (Rom. 8:33). How better to do so than congregationally, in song?

Or perhaps there has been little perceived need for such hymns because that above does the job so well. In a rhetorically brilliant metaphor based on one of our Lord’s parables, Watts pictures inclusion in the kingdom in terms of participation at a great banquet. Not only is the metaphor true—in Christ we enjoy God’s (and each other’s) company and savor countless good things—it’s winsome, and the obvious appeal of fellowship and feasting may disarm the prejudice that sours many to teaching on the divine counsel. Moreover, the metaphor makes the irony of election intensely vivid. How did it come about that misfits like you and me have a place at so regal a table? Surely not because we are better than anyone else! (The thought is laughable.) We answer our own question in stanza 4: it came about purely by grace. And an invincible grace it must be, for the irony of election is compound: not only are we unworthy of the banquet but, prior to conversion, we have no appetite for it and would spurn the invitation. Unless compelled by divine Love, all refuse to taste, just like the dwarfs in The Last Battle (who won’t enjoy Aslan’s feast for dread of being “taken in”). This is why we sing about election. To credit our presence at the feast solely to God’s generosity and not to any merit in ourselves is to glorify God’s sovereign mercy and to assure one another that our salvation is founded on something unmovable.

We finally abandon the metaphor in stanzas 5–6 to address God directly in petition. Objectors to the doctrine of predestination sometimes claim that it saps a Christian’s motivation to evangelize. But we say it is no coincidence that the best hymn on the topic culminates with a prayer for missions and church growth. An appreciation of the doctrines of grace enables us to empathize with—indeed, to recall—the plight of the stranger. He is not just stupid or stubborn; he is dead, just as we were. An appreciation of the doctrines of grace also makes us bold and patient in our witness, since we know God’s Word is victorious.

The iambic rhythms of the poem are stately and its rhymes sweet. “Doors/stores” in stanza 1 suggests an intimate, enclosed space, abundantly supplied. The slant of “songs/tongue” in stanza 2 may seem unimpressive, until it registers that the meanings of these words correspond in a way that compensates for the loss of true rhyme. They also prepare us for the concluding vision of the hymn, in which all the chosen race joins voices, hearts, and souls to sing God’s redeeming grace. Conversely, the true rhyme of “voice/choice” in stanza 3 makes more pointed the antithesis between hearing Him and choosing wretchedness, between coming and starving.

The tune, too, is stately and sweet. ST. COLUMBA (ERIN) is an old Irish hymn melody, said by the man who collected it in 1855 to have been “sung at the dedication of a chapel—County of Londonderry.” How striking it is that the Trinity Hymnal appropriates music formerly used to consecrate a literal, physical place to describe, now, the sweet and awesome spiritual “place” of which every earthly sanctuary is but a type! The sweetness is due partly to the ease with which the melody moves, step by step, up and down the scale. It’s due also to the gentle, triple-meter rhythms; to the submediant harmony at measures 4 (“place”), 8 (“ev-”), and 11 (“-plays”); to the ravishing non-chord tones in the alto in measures 3 and 10, and in the bass in measure 9; and to the perfect counterpoint between the soprano and bass as they move either in contrary directions (“How sweet and awesome is”) or in sweet parallel thirds or sixths (“while everlasting”).

The stateliness has something to do with the melody’s dignified alternation of long notes and short notes—and with the overall shape of the phrases. The melody of the first line of the stanza rises from “do” up to “sol” and back again in a symmetrical, stable arch. That of line 2 starts the same way, but the triplet (a compression of the three pulses of the meter to fit within a single beat, on the word “the”) dispels any expectation we have for another descent, so the melody can continue to its summit at the beginning of the third line, at the most exalted idea in most stanzas (“everlasting love” in stanza 1, “each of us cries” in stanza 2, “thousands” in stanza 3, “your victorious Word” in stanza 5, and “with one voice” in stanza 6). Then the melody ends with five notes (B-flat, A-flat, G, F, E-flat) sung twice (in the second half of line 3 and again in line 4) which simply reverse the order of the first five notes of the line 1. So the melody as a whole traverses two smaller, matched arches (lines 1 and 4) that together support a larger arch—the musical equivalent of a structural principle frequently seen in cathedrals. (The effect is enhanced when congregations treat the fermata in measure 7 as a slight pause for breath. Those who sustain the B-flat for five beats have been influenced by the use of this tune for another text, “The King of Love My Shepherd Is,” which has seven syllables in its second line, instead of six.)