Jerusalem the Golden

Bernard of Cluny, c. 1140; translated by John Mason Neale, 1851

Addressed to Jerusalem, to one another, and to Jesus

| Jerusalem the golden, | Rev. 21:18 |

| with milk and honey blest, | Ex. 3:8 |

| beneath your contemplation | |

| sink heart and voice oppressed. | Rev. 22:8 |

| I know not, oh, I know not, | 1 John 3:2 |

| what joys await us there; | 1 Cor. 2:9 |

| what radiancy of glory, | Rev. 21:11 |

| what bliss beyond compare. | Ps. 137:6 |

| They stand, those halls of Zion, | Ps. 87:1; John 14:2 |

| all jubilant with song, | 2 Chron. 30:21; Is. 26:1; 35:10 |

| and bright with many an angel, | Heb. 12: 22; Rev. 5:11 |

| and all the martyr throng. | Rev. 20:4 |

| The Prince is ever in them, | Ezek. 34:24 |

| the daylight is serene; | Rev. 7:16; 21:23 |

| the pastures of the blessed | Ezek. 34:14; Rev. 7:17 |

| are decked in glorious sheen. | |

| There is the throne of David; | Is. 9:7 |

| and there, from care released, | |

| the song of them that triumph, | Rev. 15:2–3 |

| the shout of them that feast; | Is. 25:6; Matt. 8:11; Rev. 19:6–9 |

| and they who with their Leader | |

| have conquered in the fight, | |

| forever and forever | |

| are clad in robes of white. | Rev. 7:9, 13–14 |

| O sweet and blessed country, | |

| the home of God’s elect! | John 15:19; 1 Pet. 1:1 |

| O sweet and blessed country | |

| that eager hearts expect! | Heb. 11:14–16; 13:14 |

| Jesus, in mercy bring us | |

| to that dear land of rest; | |

| who are, with God the Father | |

| and Spirit, ever blest. |

Observers of church life have long noted a scarcity of sermons on the topic of hell. Behind this trend lies something more than just an aversion to negative messages. There must also be a failure of conviction, for almost as scarce now are sermons on the parallel yet positive topic of heaven. The trend is evident in congregational song, too. The one above, much beloved across theological lines only a century ago, has been dropped by every mainline American protestant denomination but one in their most recent hymnals (the exception being the Episcopal Hymnbook 1982). In some cases there is no longer even a “heaven” heading in the topical index. All this reflects a fundamental change in the way Christians think. The materialism, secularism, and—frankly—brutality of modern culture have so affected our eschatology that few Christians now attach any specific meaning or images to the concept of heaven (or so sociologists tell us). There is even a sense that caring about it is irresponsible, that longing for heaven leads to neglect of this world.

The Bible insists on the opposite. The Letter to the Hebrews, for example, teaches that courage to live faithfully in this life comes from seeking a city that is to come (11:14–16; 13:14). Accordingly, in a 1993 essay in First Things, Robert W. Jenson urged Christians to tell each other, and the world, the whole story. We

must no longer be shy about describing just what the gospel promises, what the Lord has in store. Will the city’s streets be paved with gold? Modernity’s preaching and teaching—and even its hymnody and sacramental texts—hastened to say, “Well, no, not really.” And having said that, it had no more to say. In modern Christianity’s discourse, the gospel’s eschatology died the death of a few quick qualifications. The truly necessary qualification is not that the City’s streets will not be paved with real gold, but that gold as we know it is not real gold, such as the City will be paved with. What is the matter with gold anyway? Will goldsmiths who gain the Kingdom have nothing to do there? To stay with this one little piece of the vision, our discourse must learn again to revel in the beauty and flexibility and integrity of gold, of the City’s true gold, and to say exactly why the world the risen Jesus will make must of course be golden, must be and will be beautiful and flexible and integral as is no earthly city.

There is nothing irresponsible about historic Christianity’s classic reflections on heaven. He can neither love his neighbor nor cultivate creation who hasn’t some sense of the final meaning and fulfillment of these things—the sweet and blessed country that eager hearts expect. But how are we to incite eagerness for a country that none of us has ever visited? For a country so unlike the one we know?

The poem “Jerusalem the Golden” introduces its theme by admitting its difficulty. The bliss cannot be described, because it cannot be compared to anything in our experience (line 8). The clumsiest passage comes early, in lines 3–4: “beneath your contemplation / sink heart and voice oppressed.” Oppressed having only negative connotations now, few singers can have in mind what Bernard of Cluny intended. The translator used it in the sense of “overcome” or “overwhelmed.” Perhaps we get closer to the original Latin with something like “what heart can view your beauty / and go on, self-possessed?” The task is beyond us, because, even if we were taken to heaven for a while, the sight would leave us tongue-tied, whereas any account we dream up ourselves will be false or, at best, too abstract. Nobody can look forward to an abstraction.

Bernard’s solution was to stick to the Bible. Through the Revelation to John, God graciously provided a way for us to think accurately and concretely about heaven. Any critic who judges “Jerusalem the Golden” too sensuous must level the same complaint against Revelation, the book which many consider the most vivid in all the Scriptures—with its luminous colors and jewels; its voices like trumpets, lions, and waters; its little scroll, bitter to the stomach but sweet as honey to the mouth; its smoke and sulfur and incense; and its God who wipes tears from eyes. Physical beings (which we are—not merely physical, of course, but physical nonetheless) can only long for a physical place (a new heaven and a new earth) that they can physically conceptualize, and Bernard’s images, coming as they do straight from the Bible (see references in the right-hand margin above), are vivid indeed. The provision of milk and honey identifies the city with the land promised to Old-Testament saints. The halls are “jubilant with song.” The daylight is serene. In her poem “The Best,” Elizabeth Barrett Browning asked, “What’s the best thing in the world?”

Light, that never makes you wink;

Memory, that gives no pain;

Love, when, so, you’re loved again.

What’s the best thing in the world?

―Something out of it, I think.

Returning to Bernard’s poem, his reference to the “pastures of the blessed” resonates with the whole pastoral tradition of Christianity, inculcated in us from the time we learn the twenty-third psalm upon our parents’ laps.

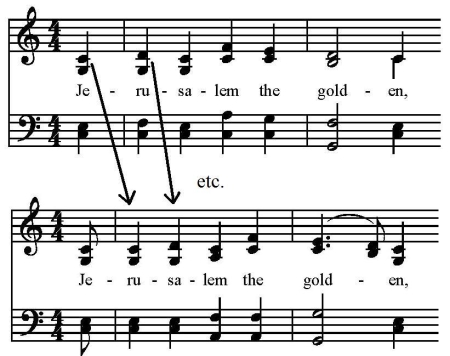

The tune EWING is just perfect. It’s certainly distinctive. Of tunes discussed on this website, it alone begins with dissonance on its first downbeat (although see the beginning of FINLANDIA), which, together with a couple other factors, clouds our initial perception of the music’s metrical structure; if it weren’t for the bar lines in the hymnbook and the accents of the poem, it would take us some time to figure out where the downbeat is. The following example compares the opening with a metrically clearer “correction,” in which the words have been shifted one note to the left.

Our “correction” is so tame it’s silly. By contrast, hear how the real tune’s half note leans on dissonant, dominant harmony for “gold-”, while metrical ambiguity (mentioned above) weakens the resolution at “-en.” Two measures later, the second line of the stanza cadences on an A-minor chord, which, because of a previous G-sharp in the melody, hints at another key (that which musicians call the relative minor). Indeed, A minor haunts this tune from start to finish. We lean on it at the end of line 3, in a way analogous to the way we leaned on the dominant in line 1, and then, again, on the very same A minor, at the end of line 5 but an octave higher (!) for the repetition of “I know not.” This is followed by a leap down and an even greater leap up to E for “joys”—the highest note and the first tonic chord to fall on a downbeat since measure 5. Only 8% of tunes discussed on this website include a high E. If not everyone can hit it, that’s o.k.; there’s something fitting about a heaven-hymn in which you can’t quite reach the top note. Altogether, EWING’s dissonance, its initially ambiguous meter, its regard for the relative minor, and its high climax communicate what Archibald Jacob called “a kind of struggling ecstasy in its phrases” (Songs of Praises Discussed, 1933) which is just right for the eager expectation of unknown joys.