Jesus, Thy Blood and Righteousness

John Wesley, 1740; based on Nicolaus Zinzendorf’s “Christi Blut und Gerechtigkeit,” 1739

Addressed to Jesus

| Jesus, thy blood and righteousness | Jer. 23:5–6; Eph. 2:13; 1 Pet. 1:2; 2 Pet. 1:1 |

| my beauty are, my glorious dress; | Is. 61:10; Zech. 3:4–5; Rev. 7:14 |

| ’midst flaming worlds, in these arrayed, | Luke 12:49; 2 Pet. 3:7 |

| with joy shall I lift up my head. | Ps. 3:3 |

| Bold shall I stand in thy great day; | Mal. 3:2; 1 Cor. 15:1; Heb. 12:28; Rev. 6:17; 7:9 |

| for who aught to my charge shall lay? | Rom. 8:33 |

| Fully absolved through these I am | 1 John 1:7 |

| from sin and fear, from guilt and shame. | Is. 54:4; Jer. 33:8 |

| When from the dust of death I rise | Ps. 22:15; 1 Cor. 15:52 |

| to claim my mansion in the skies, | John 14:2 (KJV) |

| ev’n then this shall be all my plea, | Dan. 9:18 |

| Jesus hath lived, hath died, for me. | Rom. 5:9–10 |

| Jesus, be endless praise to thee, | 2 Pet. 3:18 |

| whose boundless mercy hath for me— | Heb. 2:17 |

| for me a full atonement made, | Rom 5:11 (KJV) |

| an everlasting ransom paid. | Ps. 49:15; Matt. 20:28; Mark 10:45; 1 Tim. 2:6 |

| Oh, let the dead now hear thy voice; | John 5:25 |

| now bid thy banished ones rejoice; | Jer. 31:7–14 |

| their beauty this, their glorious dress, | |

| Jesus, thy blood and righteousness. |

The revivalist hymn may claim that “it is enough that Jesus died, and that he died for me” but Christ’s death alone is not enough to accomplish our salvation. We need Christ’s life as well, if we are to be reconciled to God. Theologians call this the active obedience of Christ—that is, Christ’s righteous living which has been imputed to us. Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf, a German nobleman whose life was full of almost ceaseless good works, knew that only Christ’s righteousness would do in the courtroom of God. His most famous hymn, translated above by John Wesley, begins by outlining the passive and active obedience of Christ—His blood and righteousness. That Wesley means a distinction here is evident from other places in the hymn. Stanza 3 points out that “Jesus hath lived, hath died for me.” Stanza 4 describes a “full atonement made,” which was accomplished at the cross, but also “an everlasting ransom”—a price paid to deliver the singer, and that price (we’re told in Matt. 20:28, Mark 10:45, and 1 Tim. 2:6) was Christ’s life, lived in total obedience to the will of God. Yet the poem is no mere versified doctrine. Its images are vivid and biblical. The word order is confusing in places, and “for who aught to my charge shall lay” in particular requires explanation from the pulpit, but compensating for this occasional clumsiness are many compelling lines.

Following Isaiah and Zechariah, Wesley describes God’s imputed righteousness and atonement in terms of dress. He then reapplies their image by drawing a terrifying apocalyptic one of his own. Flaming worlds surround us, and yet the robes of righteousness protect us from the blaze. Like Siegfried—or Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego—we walk through the fire untouched and even lift our head with joy to see our Divine Beloved.

The second and third stanzas continue the eschatological imagery of the first. The second stanza begins in the courtroom and the third ends in the rooms of the Father’s house. In either room, we rely on Christ’s atoning work and righteous life in our place. The fourth stanza praises Christ for precisely that atonement and righteous life. Here the singer’s wonder is well expressed by the interjectory repetition of “for me—for me.”

But, of course, the Last Day has not yet come. So the final stanza of this hymn petitions Christ to save more souls before it’s too late. We use two well-known biblical images: the effectual call by which God gives life to the spiritually dead (Eph. 2:1, 5) and the joy of those whose banishment from the Land of Covenant Promises, or Eden, ends (Is. 35:10). Christ calls his own to dwell with God as in Paradise. While once man dwelt there naked, he is now clothed in the blood and righteousness of Jesus.

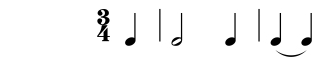

The pairing of this text with the tune GERMANY is thanks in no small part to the tune’s rhythmic shift halfway through. The first half of the tune is made up of this rhythmic motif:

The second half of the tune, in contrast, is made up of this rhythmic motif:

There are justifications for the shift in the rhythm of the text. Three of the five stanzas of this iambic poem begin with a trochee. The rhythm of the first motif is trochaic to accommodate them. The third lines of all but stanza 2 begin with an iamb. The rhythm of the second motif is iambic to accommodate them. There’s more, however, to the difference between the two motifs than their accentuation (one beginning on the downbeat and the other beginning on the upbeat) as it corresponds to the poem’s rhythm.

In every stanza line 2 closes an idea and line 3 opens a new one. So just as the rhythm of the tune changes, so do we change ideas in the text. The actual character of the motifs is important here as well—or at the very least their length. The second motif is half the length of the first. So the first half of each stanza is set to two iterations of the one motif while the second half of each stanza is set to four iterations of the other. In the second half of each stanza, lines are often subdivided (i.e.,“midst flaming worlds, / in these arrayed”; “from sin and fear, / from guilt and shame”; “their beauty this, / their glorious dress”) and these subdivisions work nicely with the four-fold division of the tune at that point. But because the second half of the tune is divided into four, not two, it seems more propulsive. Adding to this propulsion is the repetition at successively higher pitch levels of a melodic motif to correspond with the rhythmic one. So as we course past flaming worlds, as we plead our case in the court of God, and as we describe the beauty of the justified saints, we rise higher in our voices, moving quickly from one iteration of the motif to the next.