Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence

4th-century Greek prayer adapted by Gerard Moultrie, 1864

Addressed to one another and all mankind

| Let all mortal flesh keep silence, | Job 40:3–5; Hab. 2:20; Zeph. 1:7; Zech. 2:13 |

| and with fear and trembling stand; | Ps. 2:11; Phil. 2:12 |

| ponder nothing earthly-minded, | Phil. 3:19; 4:8; Col. 3:2; 1 Pet. 4:1–2 |

| for with blessing in his hand, | Lev. 9:22; Mark 10:16; Luke 24:50; Acts 1:11 |

| Christ our God to earth descendeth, | Luke 2:11; John 6:38; 1 Thess. 4:16; Titus 2:13 |

| our full homage to demand. | Ps. 2:12; John 5:23 |

| King of kings, yet born of Mary, | Rev. 17:14; 19:16; Matt. 1:16 |

| as of old on earth he stood, | |

| Lord of lords, in human vesture, | Phil. 2:7; 1 John 4:2 |

| in the body and the blood, | |

| he will give to all the faithful | Luke 22:19 |

| his own self for heav’nly food. | John 6:53–56; 1 Cor. 10:16 |

| Rank on rank the host of heaven | Ps. 68:17; Matt. 16:27; Jude 14 |

| spreads it vanguard on the way, | Luke 2:13 |

| as the Light of light descendeth | John 1:9; 8:12 |

| from the realms of endless day, | Rev. 21:25 |

| that the pow’rs of hell may vanish | John 12:31; Acts 26:18; Heb. 2:14; Rev. 19:20 |

| as the darkness clears away. | John 1:5 |

| At his feet the six-winged seraph; | Is. 6:2 |

| cherubim, with sleepless eye, | Ex 25:20; Rev. 4:8 (KJV) |

| veil their faces to the presence, | |

| as with ceaseless voice they cry, | Rev. 4:8 |

| “Alleluia, alleluia, | Rev. 19:4 |

| alleluia Lord Most High!” |

Advent is not Christmas. Advent is a minor fast while Christmas is a major feast. While we all know what it is we are to be thinking of at Christmastide, Advent is a season for contemplating both comings of the Messiah, using the watchfulness of the ancient Hebrews as they awaited the first coming to model for us a watchfulness for the second coming.[1] The hymn above began its life as an offertory (that is, a text sung at the offering up of the Eucharist) from the liturgy of St. James, but its current form, adapted by Gerard Moultrie, can be used by English-speaking congregations as an Advent hymn in the true spirit of that winter fast.

Both comings of the Messiah are interchangeably celebrated in this hymn. In the first stanza, we find Christ, our God, descending to earth, not as a tiny baby, but as someone demanding our full homage. Yet, he descends with blessing in his hand—which could be said of both his first and second comings. Though the last stanza develops a picture from the Apocalypse, the angels of the third stanza could as easily be those of Luke 2 as of Revelation 4. The third stanza’s “that pow’rs of hell may vanish,” echo Milton’s lines in his “Hymn on the Morning of Christ’s Nativity”:

Nor all the gods beside

Longer dare abide,

Not Typhon huge ending in snaky twine:

Our Babe, to show his Godhead true,

Can in His swaddling bands control the damnèd crew.

However, neither Milton nor Moultrie entirely conflate the two Messianic advents.

But wisest Fate says no,

This must not yet be so.

The powers of evil will not entirely be frustrated until the Last Day. Until that day, we celebrate Christ’s first coming and look forward to his second by means of a special feast which is the subject of the second stanza. For even Advent’s fast is broken in the Eucharistic feast.

The second stanza is more, however, than a stanza on the Eucharist. It brings together the incarnation and immolation of Christ. Christ, unchanging since the dawn of time, is nevertheless mysteriously born of a virgin. He takes on body and blood so that he can offer up his body and blood on our behalf and feed us with his body and blood in the memorial service of the Lord’s Supper, which is to last until he comes again in body and blood to judge the living and the dead.

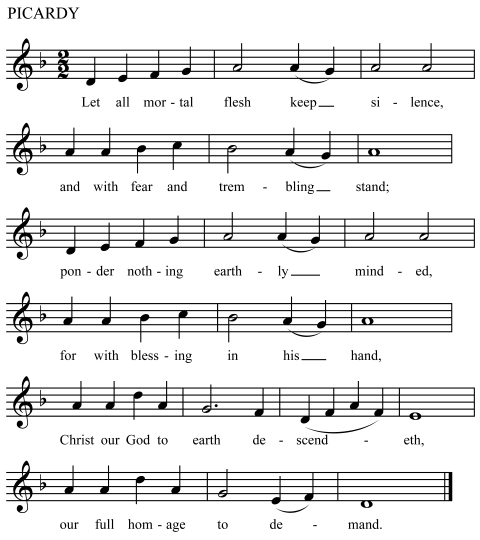

The French folk tune PICARDY, with its chant-like modality and stepwise motion, is a good pick for a text with origins as ancient as this one. Yet it departs from true chant in important and useful ways, for chant is not a congregational idiom but one that developed for specialists whose office allowed them to practice regularly in ways not afforded to the laity. First of all, PICARDY is Bar form: we sing the same phrase of music for each stanza’s second pair of lines as we do for its first pair, though we have new music for its last pair. This makes the tune at once more memorable than any chant. It also allows for useful connections between the texts of lines 1–2 and lines 3–4 in each stanza. In the first stanza, for instance, our voices and then our thoughts are silenced while singing the same tune. Then the second stanza begins with a twofold assertion of Christ’s continuing Godhead and his incarnation. The tune’s internal repetition makes this parallelism clear. PICARDY’s parallelism appears on the small scale as well. The rhythm of measures 1–2 is repeated in measuers 4–5. This means the tune’s first two-thirds has only one rhythmical phrase, sung four times. Even the tune’s last section—the setting of lines 5–6 in each stanza—has its parallelism. Both its phrases open with the exact same notes. All this repetition makes the tune more easily mastered by a congregation than any chant could be. Because this hymn, like all hymns and unlike chant, is strophic, we can sing four stanzas to that same tune without learning new music for each. Though the text has origins almost as ancient as the church itself, we can be grateful that God’s continuing Reformation has allowed it to be sung by the whole body of God’s people.

NOTE

[1] Note how the principal images of this hymn (heavenly food, light clearing away darkness, and cherubim facing the presence) recollect the furnishings of the tabernacle (Ex. 25) and temple: the table for bread, the golden lampstand, and the ark of the covenant. “The LORD is in his holy temple,” we read in Habakkuk 2:20; “let all the earth keep silence before him.”