Lift Up Your Heads, Ye Mighty Gates!

On the First Sunday of Advent

Georg Weissel, 1642; translated by Catherine Winkworth, 1855

Addressed to Jerusalem, one another, and God the Son

| Lift up your heads, ye mighty gates! | Ps. 24:7–9 |

| Behold, the King of glory waits; | |

| the King of kings is drawing near, | Rev. 19:16 |

| the Saviour of the world is here. | 1 John 4:14 |

| A Helper just he comes to thee, | Is. 41:10; Heb. 2:18 |

| his chariot is humility, | Matt. 21:5 |

| his kingly crown is holiness, | Ex. 39:30 |

| his scepter, pity in distress. | Ps. 72:13 |

| Oh, blest the land, the city blest, | Deut. 33:29; Ps. 33:12; 144:15 |

| where Christ the Ruler is confessed! | |

| O happy hearts and happy homes | Is. 60:1-5 |

| to whom this King in triumph comes! | |

| Fling wide the portals of your heart; | 2 Chr. 29:3; Song 5:2 |

| make it a temple, set apart | 1 Cor. 3:16 |

| from earthly use for heav’n’s employ, | 2 Chr. 29:4–19 |

| adorned with prayer and love and joy. | 2 Chr. 29:20–36 |

| Redeemer, come! I open wide | Matt. 3:3; Rev. 3:20 |

| my heart to thee; here, Lord, abide! | |

| Let me thy inner presence feel; | 2 Cor. 13:5 |

| thy grace and love in me reveal. | Tit. 3:4 |

| So come, my Sovereign, enter in! | Gal. 4:19; Rom. 8:10 |

| Let new and nobler life begin! | Is. 32:8; Rom. 6:4 |

| Thy Holy Spirit, guide us on, | John 16:13 |

| until the glorious crown be won. | 2 Tim. 4:8; 1 Pet. 5:4 |

In the first line of this hymn, the translator departed from the German original (literally, “raise up the door, open the gates”) to include Psalm 24’s call for the gates to lift their heads. This may strike many as a curious way to personify gates, but live with the expression awhile and it begins to make sense. The gates of the city of Jerusalem and of its temple find their functions—as a mode of defense and as a place of public deliberation—fulfilled at the advent of him who is the Rock of Israel and Judge of all the earth. It will not do for the gates merely to open, in the same way they always have, as he approaches; they will lift up their heads as if in hope, for their stop-gap labors are at an end. And, as they do so, their posture can represent that of the whole city. Not just the gates but all of Zion anticipates fulfillment and rejoices.

The translator of our hymn goes beyond Psalm 24 to call the gates mighty, but then there’s no more time for describing them, because the king’s arrival is imminent. We have the imperative “behold!” and the rhyming of “near” and “here” (the words appearing in that order). We have a pointed assertion that he comes to thee and a reference to his chariot. The idea of the Savior’s approach informs every phrase of the poem.

The point is to derive from God’s historical and physical advent—whether meeting his people in the temple, or in the incarnation of the Son, or in Jesus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem, or in his return at the end of history—a typology of our union with Christ. Without downplaying the importance of history and physical reality, the hymn nevertheless insists on a personal and spiritual application. Even in history, when Christ physically entered Jerusalem, the pressing question was whether self-righteous human hearts would receive him. Some, by regeneration, did. Hence the typology of this poem. The chariot is humility. The crown is holiness. The scepter is pity. The temple is a heart. Its adornment is prayer and love and joy. And yet note, too, that the application is not solely to the individual. The gospel has an impressive effect on society as well (stanza 3).

When sung energetically, the resounding octave ascent at the beginning of TRURO pictures the raising of the gates. It relates providentially to the opening of another important advent hymn. Sing the first eight notes, but start on a high pitch and descend instead of ascend, and you’ll find yourself singing “Joy to the world! The Lord is come.”

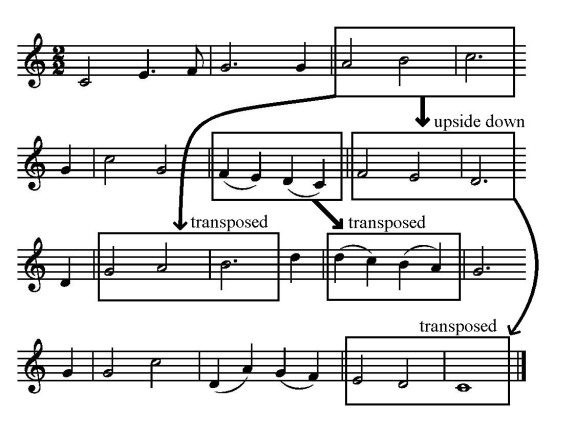

“Lift Up Your Heads” is well served by TRURO’s structure of accelerated arrivals. Right from the start we’re possessed with a sense that something unstoppable is coming, and coming so near and so soon that its approach cannot be managed but only received. This is accomplished neither by speeding up the tempo nor by contracting phrase-lengths, which would make the tune difficult, but, more subtly, by timing developments within the phrase so they come at us sooner than is normal in symmetrically-conceived melodies. The norm is established by the first melodic unit of the first line of the stanza (measures 1–2, syllables 1–4). It begins on a downbeat. But the second melodic unit of the first line (syllables 5–8) begins with a pickup (“ye” in stanza 1) and thereby encroaches on the musical space of the first melodic unit. The fifth syllable comes a quarter note earlier than the downbeat. The downbeat-beginning of line 1 is then displaced in line 2 by that same pickup. The fifth syllable of line 2 (“of”), however, is no quarter-note pickup but a two-quarter-note element absorbed into the first melodic unit of the line; in other words, the fifth syllable of this line encroaches on even more space than did the fifth syllable of the first line. The sense of encroachment is heightened by our singing four quarter notes in a row—a rhythm more swift than any yet sung. Then, in line 3, we sing a transposed variant of the second melodic unit of line 1 (see diagram) but in the first half of the line so that the end seems to overtake the beginning. Both this figure and the subsequent run of quarter notes are gripped by dominant harmony. Now there is no stopping the descending scales, and we reach low “do” on the last note of line 4—in stanza 1, on the words “is here.”

Both Weissel’s and Winkworth’s original stanzas were eight lines long, not four. The poem as printed above omits the second half of every stanza. If a congregation were to sing the stanzas whole, they could use Johann Freylinghausen’s outstanding tune MACHT HOCH DIE TÜR, a practice we heartily condone. Lutherans do this, although their versions of the words are, in our judgment, inferior to Winkworth’s own 1863 revision (see the text, but not the tune, of item 25 in The Chorale Book for England, 1863).