Lo! He Comes with Clouds Descending

The Second Advent (Rev. 1:7)

John Cennick, 1752, stanzas 3, 4, 5; Charles Wesley, 1758, stanzas 1, 2, 5; combined by Martin Madan, 1760

Addressed to all men

| Lo! he comes with clouds descending, | Is. 30:30; Matt. 26:64; Rev. 14:14–15 |

| once for favored sinners slain; | Heb. 9:28; Rev. 5:12 |

| thousand thousand saints attending | 1 Thess. 3:13; Jude 14 |

| swell the triumph of his train. | |

| Alleluia! | |

| God appears on earth to reign. | Mal. 3:2 |

| Ev’ry eye shall now behold him, | Rev. 1:7 |

| robed in dreadful majesty; | Job 37:22; Ps. 93:1 |

| those who set at naught and sold him, | Acts 2:36 |

| pierced, and nailed him to the tree, | Zech. 12:10; Heb. 10:29 |

| deeply wailing, | Amos 5:16; Matt. 24:30 |

| shall the true Messiah see. | |

| Ev’ry island, sea, and mountain, | Rev. 16:20; 21:1 |

| heav’n and earth, shall flee away; | Rev. 20:11 |

| all who hate him must, confounded, | Ps. 68:1; Mic. 7:16–17 |

| hear the trump proclaim the day: | Ps. 47:5; Joel 2:1; Matt. 24:31 |

| Come to judgment! | John 5:29 |

| Come to judgment, come away! | |

| Now Redemption, long expected, | Is. 63:4; Luke 21:28; Eph. 4:30 |

| see in solemn pomp appear! | |

| All his saints, by man rejected, | Matt 10:21; Mark 13:13 |

| now shall meet him in the air. | 1 Thess. 4:16–17 |

| Alleluia! | |

| See the day of God appear! | 2 Pet. 3:12 |

| Yea, amen! let all adore thee, | Ps. 69:34 |

| high on thine eternal throne; | Is. 6:1; Heb. 8:1 |

| Savior, take the pow’r and glory, | Mark 13:26; Luke 21:27; Rev. 19:1 |

| claim the kingdom for thine own: | Matt. 6:10; Rev. 11:15 |

| oh, come quickly; | Rev. 22:20 |

| alleluia! come, Lord, come. |

In the center of the east wall of the Sistine Chapel a cluster of angel trumpeters ride down on cloud to herald Christ’s judgment day. Two of them point to Scripture, explaining to the terror-filled inhabitants of earth that the day had been promised there. Others point their long trumpets, like blunted spears, directly at individuals below. Expressions of smug determination sit on many faces in the group. Protestants may balk at the implications of a Last Judgment painting that pictures Christ as a vindictive conqueror eager to redress the wrongs of his own crucifixion and the countless saints and martyrs that throng around him. They should re-read John’s apocalypse. Every congregation needs a hymn that terrifies unbelievers and consoles believers in its description of the Last Judgment, for this is teaching and admonition of the best sort. In our most persecuted hour, when we have (in that rarest of moments) been entirely in the right and the non-believer in the wrong, yet it is we who suffe, only this promised judgment will satisfy our desires for redress. When made to dwell richly in us, the hymn above can bring to us the satisfaction we crave in the face of injustice.

Though drawing on dozens of scriptural images about the Last Day, the hymn takes as its starting point Revelation 1:7. The first stanza opens with its image but moves quickly on to a theological proposition. Christ, the one who was once slain, is now coming in triumph on the clouds. The contrast between the Man of Sorrows and the Ancient of Days is striking, especially as we move into the second stanza. There, those who pierced him deeply wail as they see him who would have been a true Messiah even to them. The very earth itself melts away before him, to be made anew. In the fourth stanza, we turn from the condemned to the vindicated. There we find Christ described as Redemption personified, appearing before his saints who rise up to meet him. But the last stanza reminds us that all we have hitherto described has been but a biblically-informed vision of events yet to come. As Christ requires of us in the second petition of his model prayer, we are to pray that these events would come soon.

Those who do not write poetry may be under the false impression that poems come in their finished form out of a fit of muse-inspired fury, written down in perfection after hours of agonized labor from a single genius. In actuality, though this may happen, the best poets have poets as friends (one thinks of Coleridge and Wordsworth) and use those friendships as whetstones for their writing. This hymn began as a rather rough-hewn but promising work by John Cennick in 1752 and was touched up by Charles Wesley and Martin Madan (all three being leaders in the English evangelical revival) in the decade that followed. It survives to us now in a much improved form, and by that form it chiefly communicates the ideas just surveyed. The first word, “lo!” prepares us for the wonder of it all. The picture of a train swollen and filled with millions of saints is beautiful in and of itself. Here those saints become embodied triumph for the returning King. That train is attached to the robe of the second stanza, which is another embodied idea—dreadful majesty. The trumpet’s awful fanfare is then given a text: “Come to judgment! Come to judgment! Come to judgment, come away!” The four-syllable half-lines that are repeated toward the end of the stanza in all tunes (twice in HOLYWOOD/ST. THOMAS and three times in HELMSLEY) are in every instance edgy, from the trumpet call just mentioned to the breathless petition of the last stanza. Like the angels of Michelangelo’s painting, their message is direct.

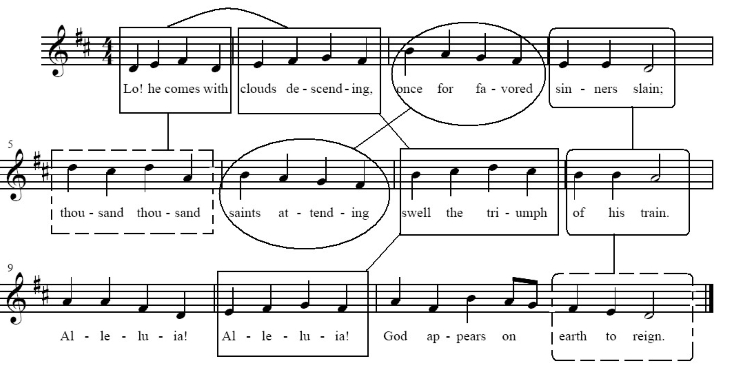

So too is the tune HOLYWOOD. The melodic motif of the first measure accounts, if transposition is allowed, for a third of the entire tune. Bring in the third and fourth measures, and you’ve accounted for eight of the tune’s twelve measures. Allow for a change in contour, and you’ve accounted for ten of the twelve (see musical example).

Yet, the repetition at the small-scale does not lead to repetition at the large scale, which lends the tune the sense that it is continually developing without any repetition whatever. Note that, though the structure of the stanza suggests lines 3–4 should be set to the same melody as lines 1–2 (as in a bar-form tune), they aren’t: they are new yet somehow familiar. Thus the tune is fitting for a hymn on the Last Judgment. For in that day, though all we see will be new to our eyes we will have a sense that all is as coherent and meaningful as if we’d been expecting it our whole lives.