O God, My Faithful God

A Daily Prayer

Johann Heermann, 1630; translated by Catherine Winkworth, 1858

Addressed to God

| O God, my faithful God, | Deut. 32:4; 1 Thess. 5:24 |

| true fountain ever flowing, | Jer. 2:13; Luthers’s Large Catechism I.25 |

| without whom nothing is, | Ps. 104:29; John 1:3 |

| all perfect gifts bestowing: | James 1:17 |

| give me a healthy frame, | Is. 38:16; 3 John 2 |

| and may I have within | |

| a conscience free from blame, | Acts 24:16; 1 Thess. 5:23 |

| a soul unstained by sin. | |

| Give me the strength to do | |

| with ready heart and willing, | Rom. 12:11 |

| whatever you command, | Gen. 12:1, 4; Jer. 1:7 |

| my calling here fulfilling— | 1 Cor. 7:17 |

| to do it when I ought, | Ex. 22:29; Prov. 10:5; 27:14; Heb. 11:8 |

| with all my strength; and bless | Luke 10:27; Col. 1:29; 3:23 |

| whatever I have wrought, | |

| for you must give success. | Ps. 127:1; Prov. 21:31 |

| Keep me from saying words | 1 Kings 12:13; James 3:2 |

| that later need recalling; | |

| guard me, lest idle speech | Ps. 141:3; Matt. 12:36 |

| may from my lips be falling: | |

| but when, within my place, | |

| I must and ought to speak, | Matt. 10:27; Eph. 4:15; Heb. 3:13 |

| then to my words give grace, | Eph. 4:29; Col. 4:6 |

| lest I offend the weak. | |

| When dangers gather round, | |

| oh, keep me calm and fearless; | Ps. 62:1; John 14:27; 1 Pet 3:6, 14 |

| help me to bear the cross | Matt. 10:38 |

| when life seems dark and cheerless; | |

| help me, as you have taught, | John 13:34 |

| to love both great and small, | Col. 1:4; James 2:1 |

| and, by your Spirit’s might, | Eph. 4:3 |

| to live at peace with all. | Rom. 12:18 |

In this hymn we petition God for the good things we need, as we have been instructed: “let your requests be made known to God” (Phil. 4:6). Making allowance for the generalities required by composed, congregational prayer, this catalog of petitions offered up for ourselves is admirably complete.

In stanza 1 we ask for health and righteousness.

In stanza 2 we ask for strength, a spirit of obedience, and God’s blessing on our work.

In stanza 3 we ask for a tamed tongue.

In stanza 4 we ask for courage, love, and peace with others.

Every major heading that one might wish included is included, at least implicitly, which is not bad for four stanzas! Pardon for sin and deliverance from temptation can be subsumed under righteousness; assurance can be subsumed under courage; our daily bread under health; wisdom under a spirit of obedience; devotion to God under love; etc.

The most important lines come first. The God of whom we ask these things is our God. (What an astounding thing, to modify God’s name with a possessive adjective; but we’re taught to do so by Scripture itself, as in Ps. 140:6.) He is faithful and generous—so generous that the flow of his gifts is likened to that of a fountain. As Jesus taught in the Sermon on the Mount: “Ask, and it will be given to you; seek, and you will find; knock, and it will be opened to you. . . . If you then, who are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will your Father who is in heaven give good things to those who ask him!” (Matt. 7:7, 11) Gifts are the theme of the hymn (line 4). We ask for them. The word “give” appears three times as an imperative and once in the form “you must give,” “keep me” appears twice, as does “help me,” and there is one instance each of “may I,” “bless,” and “guard.” We seek, in that the intent of the petitions is to pursue God’s will. And we knock, in that the poem was meant to function as a daily form for those who would persist in prayer.

The hymn commends itself especially by the usefulness of its third stanza. Every congregation ought to have in its repertoire a hymn on the perils and proper use of the tongue.

The dangers that gather round in stanza 4 are real. Although we have had very little to say in this website about the lives of authors (they being, strictly speaking, not relevant to our argument) we cannot resist describing some of Johann Heermann’s trials. He was raised in poverty, beset by poor health his entire life, and bereaved of a beloved wife when he was 31. He pastored a small town in Silesia that was largely destroyed by fire in 1615. In 1631 pestilence killed 550 members of his congregation. Repeatedly, in 1622–23, 1629, and 1632–34, his town suffered atrocities from marauding imperial troops (trying to restore Roman Catholicism during the Thirty Years’ War). In 1629 they hunted him out of town for four months, leaving his flock pastorless at a time of crisis. Later, he lost all his earthly possessions. Multiple times he was threatened by soldiers with drawn sabers. Once he fled across the Oder River in a boat over-filled with refugees and escaped a bullet only because he leaned down at just that instant to rescue a child who had fallen overboard.[1] Sometimes life does seem dark and cheerless. Then God’s aid, as near as ever, is ours to ask for.

In addition to congregational use, “O God, My Faithful God” is a practical resource for everyday prayer, in family worship and personal devotions. Since the lines are short (trimeter), and since three-quarters of them end in a rhyme, the text is easy to memorize. A change in rhythm from the first half of the stanza to the second builds a certain momentum (even without musical support), as the staid first half, alternating unrhymed six-syllable lines with rhymed seven-syllable lines, gives way to the faster pace of the second half, consisting entirely of rhymed six-syllable lines.

DARMSTADT/WAS FRAG’ ICH NACH DER WELT ranks with MUNICH as the finest of late seventeenth-century German hymn tunes.

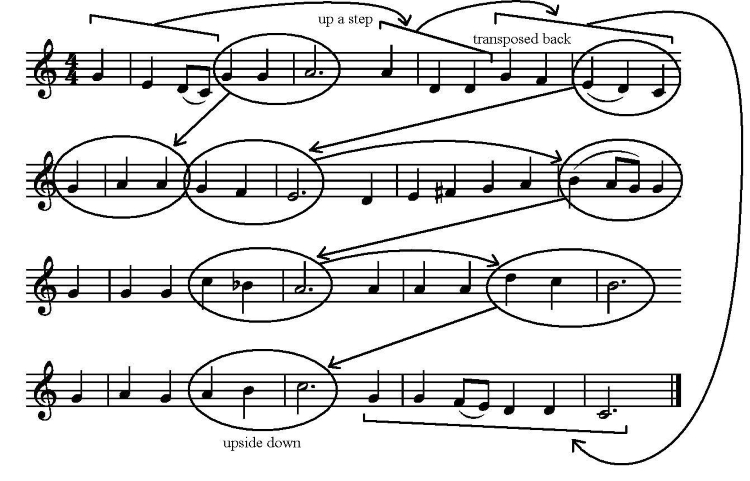

A descent of four steps from G to C (“O God, my”) is followed by an ascending step from G to A (“faithful God”). This ascending step affects the descending gesture when it returns at “true fountain,” so that it begins where “faithful God” left off, on A. Thus the two statements of the descending gesture, heard as a pair, project onto a larger scale the ascending step from G to A: the first statement starts on G and the second on A. The fourth unit of the melody (“ever flowing”) achieves closure by returning the four-step descent to its original pitch level. The slurred notes in measure 4 are perfect for the word “flowing.”

Nearly every line of the stanza terminates on a different note (the exception being line 8, which ends as line 2 did). Line 3 begins by revisiting the ascent from G to A, as if to mull over it a bit, then cadences with a three-note scalar descent, reminiscent of line 2 but transposed higher. Pitches from outside C major, appearing in measures 7 and 9, imply an intensification of the harmony. As the poetic rhythms contract halfway through the stanza (see discussion above), the melody begins to cadence ever higher. The three-note scalar descent keeps returning (see diagram), to end on G in line 4, on A in line 5, on B in line 6, and—flipping upside down to ascend to its cadence—on a decisive high C (that is, high “do”) in line 7 (“by your Spirit’s might” in the last stanza). The music that brought closure to lines 1–2 returns in line 8 to bring closure to the whole tune (“to live at peace with all” in the last stanza).

The harmonization by J. S. Bach as given in the Trinity Hymnal could be a lovely choral anthem or instrumental number, but its florid polyphony requires a tempo too slow for most congregational uses. We recommend that accompanists either simplify the texture themselves or use one of the excellent settings of WAS FRAG ICH NACH DER WELT to be found in any Lutheran hymnal.

NOTE

[1] Wilhelm Lueken, Handbuch zum Evangelischen Kirchengesangbuch, II/1, 1957, pages 139–40