Of the Father’s Love Begotten

Aurelius Clemens Prudentius, 4th c.; trans. by John Mason Neale, 1854; rev. by Henry Williams Baker, 1859

Addressed to one another, angels, and the Trinity

| Of the Father’s love begotten | Ps. 2:7; John 3:16; 1 John 4:9; Nicene Creed |

| ere the worlds began to be, | John 1:2 |

| he is Alpha and Omega, | Is. 44:6; Rev. 22:13 |

| he the Source, the Ending he, | John 1:3; Col.1:16–20; Heb. 1:2; 5:9 |

| of the things that are, that have been, | Eph. 1:10 |

| and that future years shall see, | |

| evermore and evermore! | Heb. 1:8 |

| Oh, that birth forever blessed, | Luke 1:42 |

| when the Virgin, full of grace, | Luke 1:27–28 |

| by the Holy Ghost conceiving, | Matt. 1:18, 20; Luke 1:35 |

| bore the Savior of our race; | Matt. 1:21; 2 Tim. 1:10; 1 John 4:14 |

| and the babe, the world’s Redeemer, | 1 Tim. 2:6; Rev. 5:9b |

| first revealed his sacred face, | 2 Cor. 4:6; Col. 1:15; Heb. 1:3 |

| evermore and evermore! | |

| This is he whom heav’n-taught singers | Is. 9:6; Mic. 5:2 |

| sang of old with one accord, | Luke 1:70 |

| whom the Scriptures of the prophets | Rom. 1:2 |

| promised in their faithful word; | Is. 7:14; Jer. 23:5–6; Mal. 3:1 |

| now he shines, the long-expected; | Gen. 3:15; Luke 1:78–79; Eph. 5:14 |

| let creation praise its Lord, | Ps. 69:34; Is. 44:23 |

| evermore and evermore! | |

| O ye heights of heav’n, adore him; | Ps. 148:1; Is. 49:13 |

| angel hosts, his praises sing; | Ps. 148:2; 103:20–21; Rev. 5:11–12 |

| all dominions, bow before him | Zeph. 2:11; Eph. 1:21 |

| and extol our God and King; | |

| let no tongue on earth be silent, | Ps. 145:21 |

| ev’ry voice in concert ring, | Rev. 5:13 |

| evermore and evermore! | |

| Christ, to thee, with God the Father, | |

| and, O Holy Ghost, to thee, | |

| hymn, and chant, and high thanksgiving, | Col. 3:16 |

| and unwearied praises be, | Luke 2:37 |

| honor, glory, and dominion, | Jude 25 |

| and eternal victory, | 1 Chron. 29:11 |

| evermore and evermore! |

The Oxford Movement of the mid-19th century tried to draw Anglicanism back toward its Roman Catholic roots. Those who supported the movement were doubtless encouraged by the medievalist tendencies of Victorian England. We now live in an age that has revived both Tolkien’s Middle-earth and Classical Christian (read “Medieval”) education, which is to say that we have medievalist tendencies of our own. And like 19th-century England, we are likely to conflate all things after pagan Rome but before Medici Florence into one heap, making distinctions only when they are convenient to our tastes. But the hymn printed above, though set to a modified version of a medieval chant, is really late Antique. Aurelius Clemens Prudentius (348-c.413), whose ideas are magnificently retained in John Mason Neale’s translation, was the poetic inheritor of Virgil, not Dante, and had a mind trained on the logic of Cicero, not the dark allegories of the Scholastics. One cannot help but wonder at this hymn’s inclusion into mainline hymnals, many of which have excised or radically modified hymns because of their offensively straightforward message. Is this hymn’s inclusion there simply to be justified by an irrational affection to be found in the liberal high church toward things that are medieval? If so, the hymn is sure to disappoint upon a moment’s reflection, for what could be further from, say, the ramblings of the Marian Antiphons than this compact hymn on Christ. The poetics of late antiquity require us to make connections in ideas over time, but the connections are there to make—unlike the vague mysticism of some medieval poetry. Indeed, the hymn’s only mysticism is related to its subject—the eternal begetting of Christ by God the Father. But the hymn does its best to clarify this idea so often thought of as beyond our purview.

The first stanza describes Christ as begotten of God’s love before the worlds, which would suit Arian as well as Orthodox. But Prudentius lived in the second generation of the Arian controversy and knew better than to let this line stand alone. Christ is not only begotten before the worlds began, he is much older still. He is the Alpha and the Source of the things that have been. He is Creation’s Lord (stanza 3). He is God (stanza 4). He is the one whose name begins the Trinitarian blessing of stanza 5.

Stanza 1 introduces the Christ, eternally begotten of the Father, while stanza 2 introduces Jesus of Nazareth, born of the Virgin Mary. But the Son of God and Jesus of Nazareth are the same in every way, so stanza 3 tracks Christ’s worship from the prophets to his Advent—or is it his Resurrected Glory that we meet in stanza 3, line 5? We are not to distinguish, because Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever—saeculorum saeculis (though this refrain, which Neale translates “evermore and evermore” was an 11th century addition).

In light of this truth—that Jesus of Nazareth is Christ our God—we ask all creation to worship him. The hymn is as logically tight as it can be, given its subject. Christ is begotten of God’s love, but exists before all things. He nevertheless takes human form through the womb of the Virgin, and in doing so reveals to us the very love of God through which he was begotten. He has been the object of praise “of old,” was praised throughout recorded history, and is now to be the object of praise for all creation along with the other two members of the Godhead.

The hymn, first widely circulated in English in a hymnal strongly influenced by the Oxford movement, retains Prudentius’s ideas but offers its own poetic beauties to make itself as memorable in translation as it was in the original. We make room to mention only two. Notice the inversion of the word order in stanza 1, line 4. Of course it creates the rhyme against the second line but it also creates a palindrome, where “he” begins and ends the line just as He begins and ends all things. Notice also how the alliterative “b” sounds tie together the first and second stanzas, creating unity between the stanza on Christ’s eternal nature and the one on his incarnation.

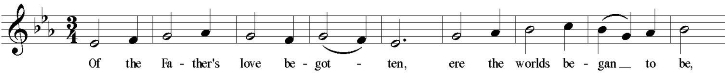

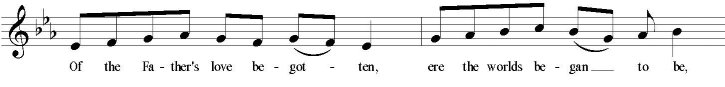

The tune DIVINUM MYSTERIUM developed, as did many chants, as an ornament on an existing chant (what music scholars describe as a “trope”). This is apparent in the similarity of its seven phrases, all of which involve arch shapes. But each arch is different and the differences relate well to the relative placement of the text in each stanza. The highest arch sets the third line of each stanza where we sing “Alpha and Omega” but also “Holy Ghost conceiving” and “chant and high thanksgiving.” The fifth arch is really the smallest one, involving only six notes, but it compensates for its brevity with a six-note extension that hovers around the dominant (that is, around the fifth scale-degree, or “sol”). Thus the tune’s fifth line is internally divided, just like the ideas of the fifth line in all but the fourth stanza.

Chant is not a congregationally conceived music. The earliest printed form of the tune (1582) prescribes for the chant a jaunty dance rhythm in three, which would doubtless make it easier for congregational song.

Some modern hymnals even use this rhythm, which—sounding more like that of a Reformation hymn-tune—perhaps undoes the quasi-medievalism that might allow some singers to treat this song as a “cultural experience” rather than as a vehicle by which congregants can speak truth to one another. Nevertheless, we recommend the rhythm of even eighth-notes found in the Trinity Hymnal.

It’s doubtful that the average congregant identifies the declamatory rhythm with the Middle Ages (or that he’d be distracted by that association). Healthy cultures of congregational singing don’t limit themselves to the rhythms of dance but employ a variety of rhythmic approaches serving a variety of communicative purposes. In this hymn, as in “Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence” and “Oh, Come, Oh, Come, Emmanuel,” the subtle freedom of a chant-like yet accessible rhythm focuses attention on the words, even as a sobering contrast to the jauntier rhythms of other hymns communicates awe and reverence appropriate for the mystery of the eternal begetting of Christ by God the Father.