Oh, Come, All Ye Faithful

John Francis Wade, 1751; trans. Frederick Oakeley, 1841

Addressed to the faithful, angels, and Jesus

| Oh, come, all ye faithful, | |

| joyful and triumphant, | |

| oh, come ye, oh, come ye to Bethlehem; | Mic. 5:2; Matt. 2:2–5; Luke 2:15 |

| come and behold him | |

| born the King of angels; | John 18:36 |

| oh, come, let us adore him, Christ the Lord. | Luke 2:15 |

| God of God, | John 1:1, 18 |

| Light of Light; | John 1:4–5; Heb. 1:3; Rev. 21:23 |

| lo, he abhors not the Virgin’s womb: | Is. 7:14; Matt. 1:23 |

| very God, | 1 John 5:20 |

| begotten, not created; | Ps. 2:7; Acts 13:33; Heb. 1:5 |

| oh, come, let us adore him, Christ the Lord. | |

| Sing, choirs of angels, | Luke 2:13–14 |

| sing in exultation, | |

| sing, all ye citizens of heav’n above; | |

| glory to God | |

| in the highest; | |

| oh, come, let us adore him, Christ the Lord. | |

| Yea, Lord, we greet thee, | |

| born this happy morning: | |

| Jesus, to thee be all glory giv’n; | John 17:5; 2 Pet. 3:18; Rev. 1:6 |

| Word of the Father, | John 1:1, 14 |

| late in flesh appearing; | 1 Tim. 3:16 |

| oh, come, let us adore him, Christ the Lord. |

In part one of this site, we rehearse the reasons why the Reformers led their congregations in the singing of strophic hymns as opposed to other existing forms of music. The strophic form allows a single simple tune to set many stanzas of text, so that we sing “Amazing Grace, how sweet the sound” to the same music as “Through many dangers, toils, and snares.” And hymns are metrical rhymed poems. Setting rhymed metrical poetry in a strophic way is central to the mnemonic success of congregational song. We find it easy to sing our songs because we are given short simple tunes for the lengthy texts. We find it easy to remember those texts because their rhyme and meter fix the texts in our minds with almost as much strength as the tune itself fixes them there. Almost. But God would not have commanded us to sing, so that the Word of Christ would dwell in us, had merely reading metrical rhymed poetry done the trick just as well. We must bear this in mind when considering the hymn above which is neither rhymed nor metrical (in its Latin original no more than in the translation above). Nor is it easily to be set in a strophic way. Perhaps neither of these shortcomings in the text has occurred to some readers. For those to whom it has occurred, please feel free to skip over the following proof:

“Faithful” does not rhyme with “triumphant,” “Bethlehem,” “him,” “angels,” or “Lord,” nor do any of those words rhyme with one another. None of the following stanzas rhyme any better either.

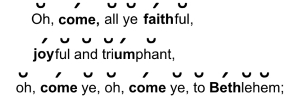

The first three lines scan as follows:

This bears no internal regularity nor comparison to the first three lines of the next stanza:

So the poem is neither rhymed nor metrical. But neither is it strophic. As will be clear to anyone who has sung all the stanzas of the song, they are not uniform in number of syllables per line. Sing the first two lines of stanza 1 followed by the first two lines of stanza 2 and the contrast is evident.

That the poem is neither strophic, metrical, nor rhymed should not surprise us when we realize that the poet was not at all Reformed, nor did he share the Reformers’ sensibilities about congregational song—in fact, he was an English Jacobite in exile. Yet, this hymn is among the most popular Christmas carols for Protestants and Catholics alike. Its text is known by heart by millions of Christians in many languages. The tune is the reason why. When God asks us to sing together, we know he does so, in part, to embed his word in our hearts. It is the tune of a hymn that does this more than anything else, and the tune to this hymn, ADESTE FIDELES, is among the most memorable of those surveyed on this site.

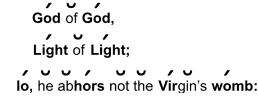

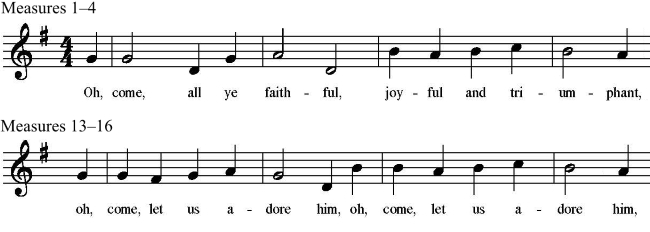

The tune’s strength comes in part from an insistent descent to the fifth scale degree, or “sol.” We hear this in the soprano in measures 1, 2, 7–8, 12, and 14 (in 25% of the measures). We also hear it implied harmonically in measures 4 and 16. Moreover, on the downbeat of measure 6, the alto takes the note that the soprano descends toward. This descending motion from “do” to the temporary repose of “sol” is an ideal metaphor for the incarnation. The tune’s strength also comes from the refrain. Everyone loves the gradual crescendo through the thrice-repeated “Oh, come, let us adore him,” where unison becomes three-voice harmony and finally a four voice texture. But it is not just the increasing number of voices—increasing as the imagined crowd at the manger increased—that makes this passage moving. We love it because we have been subconsciously prepared for it through the music that has come before. Compare the first two measures of the tune with the refrain’s first “Oh, come, let us adore him,” and the second two measures of the tune with the refrain’s second “Oh, come, let us adore him.”

The music of the stanza prefigures that of the refrain. Changes produce a sense of release: after two statements of “oh, come, let us adore him” that stick closely to what we sang earlier, there’s a thrilling ascent at the end of measure 16 that transforms the pitch C from a mere neighbor-tone of B (in measure 15) into a goal in its own right (on the downbeat of measure 17), emphatically harmonized by an A-minor chord. This high C, the peak-tone of the refrain, makes its third appearance in short succession at the end of the next measure, before the last two measures repeat the melody of measures 7–8, transposed to end conclusively on “do” instead of “sol.”

So the great tune weds this text in our mind very well. But is it as great a text as the tune is? No. But it is still a good text. The first stanza gives us context for the adoration we call for in the refrain. We are, like the shepherds and wise men, coming to worship the incarnate Christ. But his nature is not left uncharted, for the second stanza—a mere quotation from the Nicene Creed—tells us exactly to whom we come. Having established in part the nature of Christ, we call for the angels, as if their appearance to the shepherds were at our beckoning. We join in with them and all the citizens of heaven to sing to the Christ child, whose human nature we remember, by way of John’s gospel, in the last stanza. This is a word about Christ which can dwell richly in us, without the aid of rhyme, meter, or even the strophic form, because God has commanded us not merely to read his word in poetic form, but to sing.