Oh, Worship the King

Robert Grant, 1833

Based on Psalm 104

Addressed to one another, then to God

| Oh, worship the King | |

| all glorious above, | Ps. 113:4 |

| oh, gratefully sing | |

| his pow’r and his love; | |

| our shield and Defender, | Ps. 5:11–12 |

| the Ancient of Days, | Dan. 7 |

| pavilioned in splendor | Ps. 104:1 |

| and girded with praise. | |

| Oh, tell of his might, | |

| oh, sing of his grace, | |

| whose robe is the light, | Ps. 104:2 |

| whose canopy space. | |

| His chariots of wrath | Ps. 104:3–4 |

| the deep thunderclouds form, | |

| and dark is his path | 2 Sam. 22:11–13; Ps. 18:9–11 |

| on the wings of the storm. | |

| The earth with its store | Ps. 104:5 |

| of wonders untold, | |

| Almighty, your pow’r | Jer. 10:12 |

| has founded of old; | |

| has ’stablished it fast | Ps. 119:90 |

| by a changeless decree, | |

| and round it has cast, | Ps. 104:6–9 |

| like a mantle, the sea. | |

| Your bountiful care | |

| what tongue can recite? | |

| It breathes in the air; | |

| it shines in the light; | |

| it streams from the hills; | Ps. 104:10–12; Is. 41:18 |

| it descends to the plain; | |

| and sweetly distils | Ps. 104:13 |

| in the dew and the rain. | |

| Frail children of dust, | Gen. 3:19; Ps. 104:29 |

| and feeble as frail, | |

| in you do we trust, | Ps. 9:10 |

| nor find you to fail; | |

| your mercies how tender, | Lam. 3:22–23; James 5:11 |

| how firm to the end, | |

| our Maker, Defender, | |

| Redeemer, and Friend! | |

| O measureless Might! | Job 37:23; Eph. 1:19 |

| Ineffable Love! | Eph. 3:19 |

| While angels delight | |

| to hymn you above, | |

| the humbler creation, | |

| though feeble their lays, | |

| with true adoration | Ps. 145:10, 18; Mal. 1:11; John 4:24 |

| shall lisp to your praise. |

Modern democratic culture has reduced our concept of royalty to something merely picturesque, ceremonial, or historical. We serve no one and pledge allegiance to no one but ourselves (unless it be to a ball team!), and even those who remain nominally subjects of a monarch usually live as functional democrats. We have good reasons for championing political equality, but, to the extent we succeed, we need all the more to resist the age-old inclination to conceptualize God according to the political models of this world. For the kingdom of heaven is no democracy. Christians today typically share with non-Christians a sense of individual autonomy, but they are in fact subjects of a king (1 Sam. 12:12; Matt. 6:33; Col. 1:13). We must not treat service, allegiance, and worship as fictional or ceremonial categories. We belong to the kingdom of God, and to think biblically we must recover what it means to live and die in the service of our sovereign Lord.

The first four verses of Psalm 104 describe God in kingly terms that the poet of this hymn, Robert Grant, vividly develops, overtly calling God “King” in his opening line. The Ancient of Days, whom Daniel saw enthroned in judgment, is “pavilioned in splendor and girded with praise.” His regalia are the very elements of the cosmos: light and space. From high above he rides to battle through the storm. In creating the earth, he acted by changeless decree and set up a treasury of wonders.

And what kind of a king is God? Grant follows the psalmist in shaping his poem to emphasize the king’s power and love—divine attributes that go together and cannot be separated, except by theological abstraction. We are to “sing his pow’r and his love.” Put power and love together and what do you have? A shield. A defender. Stanza 2 restates the charge of stanza 1, line 4: we are to tell of his might (i.e., power) and his grace (i.e., love). So, in stanza 3, we tell of his mighty works of creation—and we shift from addressing one another to addressing God himself. Then, in stanza 4 we sing of his caring works of providence. In a sweeping summary of Ps. 104:10–30, we attempt the impossible. We try to recite how his care breathes and shines, how it streams and descends and sometimes just materializes, like dew on the grass. Stanza 5 contrasts God’s love with man’s propensity for evil. We are frail children of dust. Literally. Our forebears once were dust, and to dust they did return because of their sin. And stanza 5 also contrasts God’s power with our feebleness. His mercies are both tender (i.e., loving) and firm (i.e., powerful). We trust him and find that he never fails us. In wonder, our worship is reduced to a mere listing of titles: God is “our Maker, Defender, Redeemer, and Friend.” Stanza 6 summarizes: he is “measureless Might” (referring back to st. 3) and “ineffable Love” (referring back st. 4). Unfortunately, many hymnals obscure Grant’s twofold design by reproducing a corrupt version of the most critical line: instead of “oh, gratefully sing his pow’r and his love,” one often finds “and gratefully sing his wonderful love.”

Stanza 6 brings us back to where we started. The exhortation to worship the King has been heeded, and there is true adoration in the lisped praise of all who mean these words. The poet enhances the sense of closure here by beginning and ending stanza 6 with the same words with which he began and ended stanza 1 (“O” at the beginning and “praise” at the end).

The poem is a call to action realized. This poetic movement from potentiality to action is complemented by the unusual meter. The five-syllable lines in the first half of the stanza create a starting-and-stopping effect, which, in the second half of the stanza, gets swept away in a flowing stream of anapests. We can represent this visually with an “x” for a metrically unaccented syllable, a slanting stroke for a metrically accented syllable, and two vertical lines for the starting-and-stopping effect:

lines 1–2: x / x x / ║ x / x x /

lines 3–4: x / x x / ║ x / x x /

lines 5–6: x / x x / x x / x x /

lines 7–8: x / x x / x x / x x /

Or, using boldface type to indicate accented syllables in the first stanza:

Oh, worship the King ║ all glorious above,

oh, gratefully sing ║ his pow’r and his love;

our shield and Defender, the Ancient of Days,

pavilioned in splendor and girded with praise.

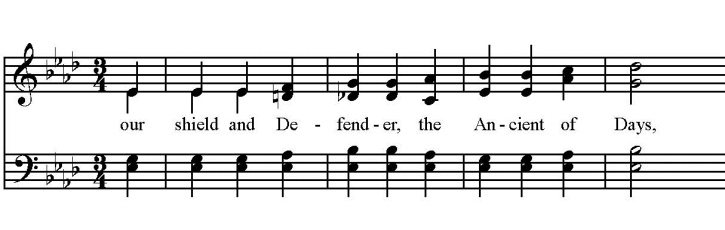

The tune LYONS (1815) greatly heightens this tendency of lines 5-6 to sweep away any hesitance that lingers in the air. The melody in the first four lines rises (“worship the King”), falls (“glorious above”), rises (“gratefully sing”), and falls again (“pow’r and his love”) in tidy arches that, together, constitute a harmonically closed unit. Then, in the fifth line, it climbs inexorably, step by step, for almost an octave, while, below, the bass holds firmly to the fifth scale-degree.

The musical energy of these lines never lets up but is sustained and compounded over the course of eleven syllables to be released only in lines 7-8. Next time you sing this in church, consider the swell at “His chariots of wrath the deep thunderclouds form,” or “it streams from the hills; it descends to the plain”—images of God’s approach. The effect is just right. So, too, is the placement of “pow’r” and “girded” in the first stanza on the highest note and most active rhythm. Thus the tune does its part to elicit an acknowledgment of his royal majesty.