Onward, Christian Soldiers

Sabine Baring-Gould, 1864

Addressed to one another

| Onward, Christian soldiers, | Phil. 2:25; 2 Tim. 2:3 |

| marching as to war, | 2 Cor. 10:3; 1 Tim. 1:18 |

| with the cross of Jesus | 1 Cor. 1:17–31 |

| going on before: | Gal. 6:14 |

| Christ the royal Master | |

| leads against the foe; | Heb. 12:2 |

| forward into battle, | |

| see, his banners go. | Matt. 16:24 |

| At the sign of triumph | |

| Satan’s host doth flee; | 1 Sam. 14:15–16; 1 John 2:13–14 |

| on then, Christian soldiers, | |

| on to victory: | 1 Cor. 15:57 |

| hell’s foundations quiver | Jer. 50:15; 2 Cor. 10:4 |

| at the shout of praise; | Josh. 6:16 |

| brothers, lift your voices, | |

| loud your anthems raise. | Neh. 12:43 |

| Like a mighty army | Ezek. 37:10 |

| moves the church of God; | |

| brothers, we are treading | |

| where the saints have trod; | Jer. 6:16 |

| we are not divided, | |

| all one body we, | Eph. 4:4–6 |

| one in hope and doctrine, | |

| one in charity. | John 13:35 |

| Crowns and thrones may perish | Prov. 27:24; Is. 10:13 |

| kingdoms rise and wane, | |

| but the church of Jesus | |

| constant will remain; | Ps. 145:13 |

| gates of hell can never | |

| ’gainst that church prevail; | |

| we have Christ’s own promise, | Matt. 16:18 |

| and that cannot fail. | |

| Onward, then, ye people, | |

| join our happy throng, | |

| blend with ours your voices | Ps. 95:1 |

| in the triumph song; | |

| glory, laud, and honor | |

| unto Christ the King: | |

| this through countless ages | |

| men and angels sing. | Rev. 5:13 |

When hymns about spiritual warfare fell out of favor with many church leaders and hymnal editors in the late twentieth century, this one bore the brunt of their scorn. Its assertive, optimistic tone seemed bellicose. Its tune, the most march-like in the book. Yet ordinary Christians would not hear of its demise. “There is probably no hymn in The [Episcopal] Hymnal 1982 as controversial as this,” reported the contributors to that hymnal’s Companion. When the Hymnal Revision Committee of the United Methodist Church deleted “Onward, Christian Soldiers” from their list in 1986, it made the front page of the Nashville Tennessean and national television news on CBS and NBC. Within six weeks the committee had received 11,000 letters, of which only 44 were in support of their action. The hymn was soon restored to the list.[1] The mainline Presbyterians, however, successfully removed it from their denominational hymnal in 1990. The mainline Lutherans from theirs in 2006.

We, the authors of this web site, agree that it’s imprudent to sing this hymn when congregants may be prone to apply its message temporally—for example, immediately after their nation has declared war on another. But we contend that it’s imprudent not to sing it in other contexts. The Bible states that the Christian life requires the kind of alertness and fortitude found on a field of battle. The church is like an army; each of us is part of something larger, and we’re on the move. To neglect this teaching is to leave a passive church needlessly unprepared for the onslaughts of temptation and the devil.

From this perspective, there’s nothing in “Onward, Christian Soldiers” at which to take offense. The poet declares the military imagery mere metaphor. (Christian soldiers are to march “as [if] to war.” The church moves “like” a mighty army.) The enemy being identified as “Satan,” we’re not at liberty to appropriate the hymn to some other war of our own making. And, note, we are united “in charity.”

Sure, the poet mentions none of the darker realities of combat, but these would not be germane to his purpose. It’s good in other hymns to acknowledge that “fierce may be the conflict, strong may be the foe” (Who Is on the Lord’s Side) and that men see the church “sore oppressed, by schisms rent asunder, by heresies distressed” (The Church’s One Foundation). But the purpose of “Onward, Christian Soldiers” is to incite us to motion and to give us reasons for confidence. “Onward!” begin the first and last stanzas. Elsewhere it’s “forward into battle!” and “on then, Christian soldiers, on to victory!” The church of God “moves,” and, finally, “ye people” are to “join our happy throng.” The reasons for such active happiness are an assurance of evil’s defeat (stanza 2), the essential unity of the catholic or universal church (stanza 3), and our Lord’s promise in Matthew 16:18 (stanza 4).

The short, perfectly rhymed lines of poetry are appropriate for a message so simple. The trochaic rhythms command attention, like a call to arms (see our study of “Let Us Love and Sing and Wonder”). Notice too the boisterous alliteration throughout (as in stanza 1: “Christians,” “cross,” “Christ,” “foe,” “forward, “battle,” “banners,” or stanza 4: “crowns,” “kingdoms,” “constant,” “cannot”). The poem is full of plosive sounds that burst from the mouth like a cannon ball.

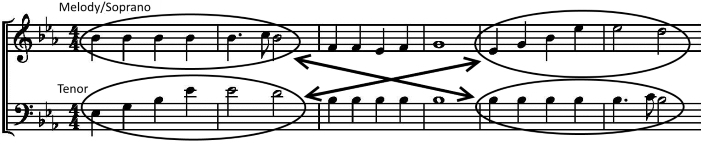

The tune ST. GERTRUDE is a masterful adaptation of march-like gestures to a congregational vocal idiom. The most obvious of these is the bass line of the refrain. It’s all about movement, as the text says. From the start, the soprano/melody conveys a sense of propulsion when repeated notes (measures 1–2) grow into a melodic motif (measures 3–4) and then into an arpeggio that reaches an octave (measures 5–6). Later, the prolonged predominant and dominant harmonies of measures 13–17 (lines 7–8 of the stanza) build anticipation for a resolution to the tonic that arrives only at the downbeat of the refrain. There the voice settles on “do” for the first time in the tune, for a stirring transformation of the monotone opening (back in measures 1–2).

In measures 1–2 and 5–6 the soprano and tenor exchange parts

as if listening to one another’s calls to action. “Blend with ours your voices,” they sing in stanza 5.

NOTE

[1] Carlton R. Young, Companion to the United Methodist Hymnal (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1993), 135–36.