Rejoice, the Lord Is King

Rejoice Evermore

Charles Wesley, 1746

Addressed to one another

| Rejoice, the Lord is King: | Ps. 97:1, 12 |

| your Lord and King adore! | Ps. 145:1 |

| Rejoice, give thanks, and sing, | Is. 51:3b; James 5:13b |

| and triumph evermore. | 2 Cor. 2:14 |

| Lift up your heart, lift up your voice! | Is. 24:14 |

| Rejoice, again I say, rejoice! | Phil. 4:4 |

| Jesus the Savior reigns, | Rom. 15:12 |

| the God of truth and love; | |

| when he had purged our stains, | Heb. 1:3b |

| he took his seat above. | Eph. 1:20 |

| Lift up your heart, lift up your voice! | |

| Rejoice, again I say, rejoice! | |

| His kingdom cannot fail, | Is. 9:7; Luke 1:33 |

| he rules o’er earth and heav’n; | Phil 2:10 |

| the keys of death and hell | Rev. 1:18 |

| are to our Jesus giv’n. | |

| Lift up your heart, lift up your voice! | |

| Rejoice, again I say, rejoice! | |

| He sits at God’s right hand | Col. 3:1 |

| till all his foes submit, | Ps. 110:1-2 |

| and bow to his command, | |

| and fall beneath his feet. | 1 Cor. 15:25; Heb. 10:13 |

| Lift up your heart, lift up your voice! | |

| Rejoice, again I say, rejoice! | |

| Rejoice in glorious hope! | Rom. 12:12 |

| Our Lord, the Judge, shall come, | Acts 1:11; 17:31 |

| and take his servants up | 1 Thess. 4:17 |

| to their eternal home. | |

| Lift up your heart, lift up your voice! | |

| Rejoice, again I say, rejoice! |

To study congregational singing is to be continually impressed by the difference between Christian songs and what we would sing if left to ourselves (assuming we would sing at all). Charles Wesley’s “Rejoice, the Lord Is King,” is just the sort of song that only the Lord could put in our mouths. For neither its insistence on joy nor its linking of joy to Christ’s ascension makes sense apart from faith.

First, there is the insistence that we “rejoice always,” as the apostle puts it in 1 Thessalonians 5:16. What are we supposed to do with that? If one accepts that a state of mind is the sort of thing that can be commanded, there still remains the tricky adverb “always.” Quite apart from our contrary propensity—to complain always—we struggle to take this exhortation literally because Scripture itself indicates that believers will be grieved by various trials, and grief seems incompatible with joy.

Second, the ascension was a grievous trial if ever there was one. To those without faith a celebration of it may seem an exercise in wishful thinking, escapism, or rationalization. We say that Jesus triumphed over death and lives forever as someone we can know personally, but where is he? And what is there to celebrate in the removal of the Shepherd from the flock? Suspecting emotional dishonesty, the world construes the doctrine of the ascension as a flimsy attempt to explain away Christ’s inconvenient absence. Even those with some faith may in their lonelier hours rue his withdrawal from the gaze of mortals. In Goethe’s Faust, the disciples lament:

Though he, the buried one, has ascended now alive, sublime; though he, in the bliss of becoming, is near creative joy; we, alas, are left on the breast of the earth to suffer. Since he left us, his very own, here to languish, we weep at your exaltation, Master![1]

Their complaint, however, misrepresents the event. Far from abandoning them, the ascension transformed their fellowship with the humiliated Christ, restricted as it was by place and time, into a fellowship with the ruler of the universe, unrestricted by place and time.

For Christians, then, suffering on earth is compatible with joy (2 Cor. 6:10; 1 Pet. 1:6) because, being united with Christ who is ascended on high, we are blessed with every blessing in the heavenly places even as we suffer. The ascension really is key to Christian joy. Although we delight in all God’s works of salvation, the ascension in particular establishes the joyous fact that the savior on whom we’ve placed all our hopes is sovereign. He is King, forever—that he might fill all things and be with us always.

The theme of the permanence of his reign and of our joy frames the hymn above, with references in the first stanza (“triumph evermore”), the central stanza (“His kingdom cannot fail”), and the last stanza (“to their eternal home”). As a framing device, it emphasizes the ongoing nature of Christian joy. Joy cannot be exhausted by time or adversity. This is the point of the Apostle Paul’s famous repetition in Philippians 4:4. “Rejoice in the Lord always; again I will say, Rejoice.” In Wesley’s hymn these words become a refrain; that is, Wesley revisits the repetition at the end of each stanza and thereby projects its rhetorical effect onto a higher level of perception. As both sentence and stanza come round again to joy, so presumably does everything else.

In the first stanza we sing the word “rejoice” no fewer than four times. The parallel openings of lines 1, 3, and 6 prepare us for a farther-reaching parallelism between the first and last stanzas, both of which begin with “rejoice.” Similarly, the first stanza shares with the song as a whole the same first and last word: “rejoice.”

The framing and the repetition cooperate with several other rhetorical masterstrokes to produce great clarity. Notice how the first line encapsulates the sense and the structure of the whole song. The first word is in the imperative mood—rejoice!—while the next four words, in the indicative mood, justify that imperative—because “the Lord is King.” The same proportions recur over the hymn as a whole: one largely imperative stanza, followed by four largely indicative stanzas expanding on the royal grounds for joy.

The imperative of stanza 1 is underscored by both chiasmus and climax. The chiasmus comprises lines 1 and 2, where the word order of line 1 (imperative verb + the nouns “Lord” and “King”) flips around in line 2 (the nouns “Lord” and “King” + imperative verb). The return to an imperative verb at the end of line 2 launches a string of imperatives arranged in ascending order of intensity across lines 3–4, climaxing with “triumph” and the adverb “evermore.”

The theme of height in stanzas 1–3 (“lift up,” “his seat above,” “he rules over earth and heaven”), so appropriate for ascension, gets inverted in stanza 4 (“He sits at God’s right hand till all his foes submit, and bow to his command, and fall beneath his feet”) to throw into relief the return to height at the end: “and take his servants up.”

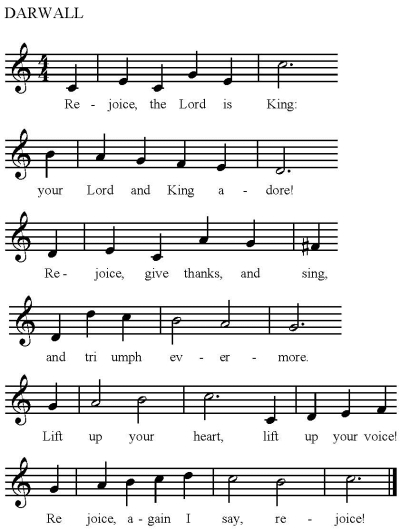

Any tune joined to this text should make something of its height theme. DARWALL does with a dramatic ascent at “lift up your heart” and an even more dramatic ascent, climbing stepwise from the lowest note of the song to the highest, at “lift up your voice.” This satisfies not only our poetic imaginations (as we think about lifting) but our musical imaginations as well, for it balances a stepwise descent from the beginning of the melody (“your Lord and King adore”). In between, the most exuberant gesture, an upward octave leap from low D to high D, occurs at stanza 1’s climactic “triumph” as well as Christ’s enthronement (stanza 2) and our own ascension (stanza 5). This connects, through a bold melodic gesture, the two main points of the hymn—the ascension of Christ and our uplifted joy.

(Unfortunately, the Trinity Hymnal promiscuously assigns DARWALL to five texts and thereby effectively spoils its considerable mnemonic power—unless congregations have the foresight to select one text and stick with it. One popular candidate, Horatius Bonar’s “Thy Works, Not Mine, O Christ,” though not without merit, is crippled by an impossibly garbled refrain: “To whom, save thee, who canst alone for sin atone, Lord, shall I flee?” We believe not one in three congregants knows what he’s asking in this question. And, since the text says nothing about height or ascent, the distinctive contours of the melody are squandered to no communicative purpose. A congregation that wishes to use DARWALL for another text can use the fine tune ARTHUR’S SEAT for “Rejoice, the Lord is King.” Like DARWALL, it climbs dramatically in the refrain.)

DARWALL

ARTHUR'S SEAT

NOTE

[1] Hat der Begrabene

Schon sich nach oben,

Lebend Erhabene,

Herrlich erhoben;

Ist er in Werdelust

Schaffender Freude nah;

Ach! an der Erde Brust

Sind wir zum Leide da.

Ließ er die Seinen

Schmactend uns hier zurück;

Ach! wir beweinen,

Meister, dein Glück! (part 1, lines 785–796)