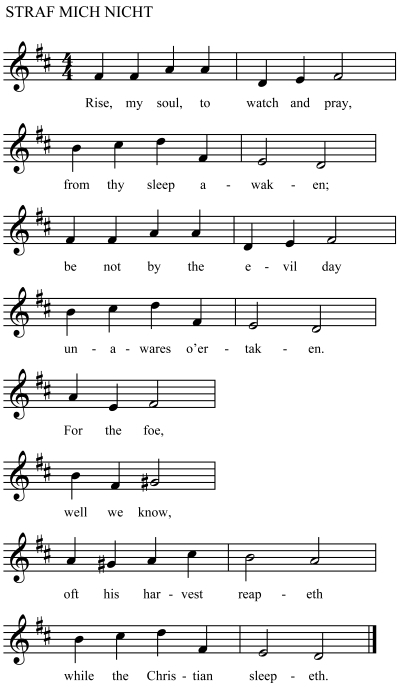

Rise, My Soul, to Watch and Pray

J. B. Freystein, 1697; trans. C. Winkworth, 1863, and The Lutheran Hymnal, 1941

Addressed to oneself

| Rise, my soul, to watch and pray, | Matt. 25:13; 26:41; Mark 13:33 |

| from thy sleep awaken; | Rom. 13:11; 1 Cor. 15:34; Rev. 3:2 |

| be not by the evil day | Eph. 5:16 |

| unawares o’ertaken. | 1 Thess. 5:3–4 |

| For the foe, | |

| well we know, | |

| oft his harvest reapeth | |

| while the Christian sleepeth. | |

| Watch against the devil’s snares, | 2 Cor. 2:11; Eph. 6:11; 1 Pet. 5:8 |

| lest asleep he find thee; | |

| for indeed no pains he spares | |

| to deceive and blind thee. | Matt. 4:1–11; 1 Thess. 3:5 |

| Satan’s prey | |

| oft are they | |

| who secure are sleeping | |

| and no watch are keeping. | Gen. 3:6 |

| Watch! Let not the wicked world | Matt. 18:7 |

| with its pow’r defeat thee. | Rom. 12:2 |

| Watch lest with her pomp unfurled | 1 John 2:16 |

| she betray and cheat thee. | Matt. 13:22 |

| Watch and see | |

| lest there be | |

| faithless friends to charm thee, | Jer. 29:8; Gal. 2:4; Jude 12 |

| who but seek to harm thee. | |

| Watch against thyself, my soul, | Deut. 4:15; Luke 21:34; Gal. 6:1; 1 Tim. 4:16 |

| lest with grace thou trifle; | Rom. 6:1; Heb. 2:3 |

| let not self thy thoughts control | Rom. 6:12; 1 Cor. 10:24 |

| nor God’s mercy stifle. | |

| Pride and sin | |

| lurk within | Gen. 4:7 |

| all thy hopes to scatter; | Prov. 16:18; Jer. 3:24 |

| heed not when they flatter. | |

| But while watching, also pray | Eph. 6:18 |

| to the Lord unceasing. | 1 Thess. 5:17 |

| He will free thee, be thy stay, | Ps. 18:18; John 8:36 |

| strength and faith increasing. | Eph. 3:16 |

| O Lord, bless | |

| in distress | |

| and let nothing swerve me | Matt. 6:13 |

| from the will to serve thee. |

Curiously, the same Bible which assures believers that their salvation is complete and which forbids them to be anxious also commands them to wake, watch, beware, be ready, be alert, and be on guard some forty-four times in the New Testament alone. If God is victorious, why does he still set a watch? If his enemies are vanquished, against what are we guarding? Sometimes one of the fruits of victory is a new capacity to set a proper watch, as did, for example, modern Israel on the Golan Heights after the 1967 Six-Day War. Only, the permanent victory of the cross gives watchful believers far more confidence than any earthly guardsman may have over his post. For the spiritual watch that comes after Christ’s victory is not a watch against an invading army with power to conquer or mount a lengthy siege, but against the once-conquered rebel who is truculent enough not to concede his obvious losses. We watch, not because the enemy has power “to lead astray, if possible, the elect” (Mark 13:22). It isn’t possible (Rom. 8:38–39). We watch because God is pleased to trounce, again and again, his defeated enemies, and to use the weakest of possible means to do so.

Printed above is one song that myriad Christians have learned to sing in the long watches of the soul’s night. A summary of biblical warnings stimulates the living soul the way coffee does the body, counteracting lethargy and rousing one to attention and activity. The warnings, although concise, systematically alert us to the dangers we face if God for even a moment would withdraw his shield: satanic dangers (stanza 2), worldly dangers (stanza 3), and dangers within (stanza 4). We are soldiers in a spiritual conflict and shall, for God’s glory, have to encounter enemies now and then, and perhaps even be hurt by them. The only question is whether we shall confide in our own strength like Peter on that harrowing Thursday night (“Lord, I am ready to go with you”) only to learn through tears how weak we are, or whether, anticipating our vulnerability to every kind of sin, we shall depend on God.

This is why in Gethsemane Jesus instructed his disciples to watch and pray (stanza 1, line 1), and why our hymn, after urging us to watch in stanzas 2–4 (indeed, it’s the first word of each of these stanzas) culminates with the imperative of prayer. Commenting on Mark 14:38, R. Alan Cole described the kind of prayer Jesus had in mind as, “at one and the same time, a confession of the weakness of our own flesh and a showing forth of the readiness of our spirit by the very act of prayer, joined with a realization of the power of God to whom we pray.”[1] We beseech the Lord to watch over the city, as Psalm 127:1 puts it, because without him “the watchman stays awake in vain.”

Both poem and tune mimic the behavior of somebody shaking off sleepiness to keep fully alert. The unique structure of the stanza accelerates abruptly halfway through to give us rapid-fire lines of three syllables in a rhyming couplet, in contrast to the much longer lines 1–4 with their alternating rhyme. One’s heart skips a beat at words like “for the foe,” “Satan’s prey,” “pride and sin,” and “O Lord, bless.”

In the first half of STRAF MICH NICHT, the melodic gestures in each measure ascend, except at cadences. The gestures connect to one another by large skips down and up. Then, just where the poetry quickens its rhythm, we get a gesture that includes a skip (measure 9). It immediately repeats itself, transposed up a whole step; we lunge harmonically through tonal space, with two notes from outside the key appearing simultaneously: G-sharp in the melody and D-sharp in the chords below it, both raised a half-step from the corresponding notes of the home key (measure 10). We find ourselves firmly established in the bracing atmosphere of another key (the tonic of which is the dominant of the home key), but it’s short-lived. Line 8 exerts itself to climb to the peak tone with G-naturals in the tenor below and achieves closure by returning to the music (and cadence) of lines 2 and 4.

NOTE

[1] R. Alan Cole, The Gospel According to Mark (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1961), 220.