Tell Me the Old, Old Story

Katherine Hankey, 1866

Addressed to one another

| Tell me the old, old story | Acts 8:31; 13:42 |

| of unseen things above, | John 3:3; 1 Cor. 2:9; 2 Cor. 4:18 |

| of Jesus and his glory, | 2 Cor. 4:4 |

| of Jesus and his love: | Eph. 3:19 |

| tell me the story simply, | 1 Cor. 2:1 |

| as to a little child, | Ps. 131; Luke 18:17 |

| for I am weak and weary, | Ps. 6:6 |

| and helpless and defiled. | Jer. 3:13 |

| Tell me the story softly, | 1 Thess. 2:7 |

| with earnest tones and grave; | |

| remember, I’m the sinner | |

| whom Jesus came to save: | 1 Tim. 1:15 |

| tell me the story always, | Ps. 96:2 |

| if you would really be, | |

| in any time of trouble, | |

| a comforter to me. | Ps. 119:50 |

| Tell me the same old story, | |

| when you have cause to fear | Ps. 51:13; James 5:19 |

| that this world’s empty glory | Ps. 49:20; Eccl. 1–2; John 5:44 |

| is costing me too dear: | Matt. 13:22; Mark 10:23 |

| yes, and when that world’s glory | |

| is dawning on my soul, | John 12:43 |

| tell me the old, old story, | |

| “Christ Jesus makes thee whole.” | Acts 9:34 |

Among the cruelest afflictions of our fallen condition is the way knowledge, which ought to humble us, instead tempts us to pride. It puffs up (1 Cor. 8:1). The affliction is cruel because humility is not just the appropriate result of knowledge gained, it generally is necessary for the very gaining of it. Pride interferes with learning to create a vicious circle—we need humility to learn but learning makes us proud. This is why the Apostle Paul so forcefully taught that along with all the rest of our being our minds, too, must be rescued and transformed by the gospel of Jesus Christ. And why Martin Luther’s rediscovery of this teaching became fundamental to Protestant doctrine. All knowledge worthy of the name begins and ends at the foot of the cross.

We believe the hymn above is of great value for the clear way it voices a continuing interest in the gospel from a position of humility. Looking outside ourselves, we turn to others and ask not for some speculative debate about God’s eternal power and divine nature, but, like children, we ask to be told a story. Like very young children, we ask to hear the same one repeatedly, making it doubly “old”: ancient but also heard before. This is no “regressive and infantile posturing,” as one eminent hymnologist has dismissively characterized it[1]—those who feign childhood do not use words like “weary” and “defiled”—only realistic mortification of pride in the face of lofty topics like unseen things above, Jesus, his glory, and his love.

The rest of the hymn describes, in a progression of requests that builds to a meaningful climax, how we would like the story to be told. First, we request that it be told simply with just the historical and theological facts so we’re not distracted by tangents or merely human interpretations. Next, we ask that the story be told softly (that is, gently) because parts of it may be difficult and earnestly because much is at stake: we are sinners, indeed, the very sinners whom Jesus came to save. We ask that it be told always, in both good and bad times, because it alone can comfort. Above all, in stanza 3, we ask to be told the story when our straying hearts begin to prefer some other story. Hankey’s description of the world’s glory as something which, though empty, can nevertheless “dawn” on the soul and cost it dearly, sticks in the memory. And it sets us up for the climactic last word of the hymn, where the wholeness of life in Christ contrasts with the emptiness earlier in the stanza.

“Tell Me the Old, Old Story” should not be confused with the other, similarly named, “storytelling” hymns in the Trinity Hymnal. Sometime after writing it, Hankey also wrote “I Love to Tell the Story” to be a companion piece from the perspective of the storyteller. Unfortunately, being an unstructured list of reasons (and some of them pretty vague reasons) why I love to tell the story, it lacks the focused train of thought of the earlier poem. It must have frustrated Fanny Crosby, another hymn writer, that Hankey’s poems never get around to telling the story they claim to love, for in 1880 Crosby wrote one, “Tell Me the Story of Jesus,” which embeds the story in our very request for it. “Tell how the angels, in chorus, sang as they welcomed his birth, . . . of the years of his labor, . . . of the cross where they nailed him, . . . of the grave, . . . how he liveth again.” But a hymn can only do so much, and the treatment of each part of the story remains superficial. The result is at times sentimental (“stay, let me weep while you whisper”). By contrast, the genre’s prototype, “Tell Me the Old, Old Story,” offers both focus and substance.

In the poetry, both rhythm and rhyme do their part. The shortness of the lines, with only three metrical feet in each, accords with the simplicity we are asking for. Within most of these lines, Hankey managed to place the richest word at the end, where rhyming sounds underscore its importance.

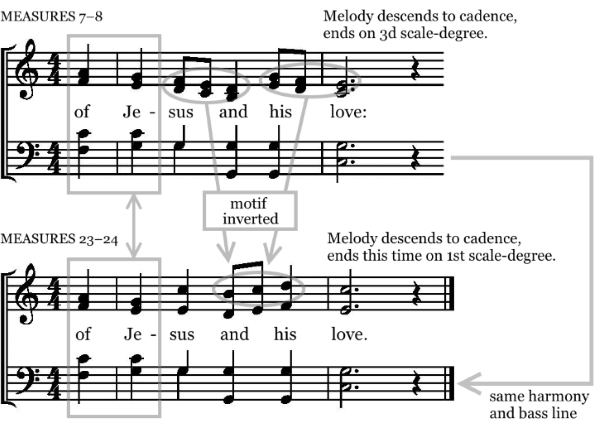

The tune does its part, too. As we sing the second line (“unseen things above,” “earnest tones and grave,” “when you have cause to fear”) which in every stanza sobers us for what is to come, the tune hangs on a somewhat unusual minor chord (the submediant), inserts a chromatic note, and cadences on an unstable sonority (notice how the chord on the downbeat of measure 4 must resolve itself in the alto and tenor). The third line then recasts the three high Cs from line 2 with a more emphatic tonic harmony (“of Jesus and,” “remember I’m,” “that this world’s empty”). The fourth line descends to a low D in what we anticipate will be a conclusive cadence on low C (the first scale-degree, “do”). Except that is not what happens. We don’t reach low C. At “his love” (and “to save” in stanza 2 and “too dear” in stanza 3) the melody repeats its descent, only to cadence on a poignant E (the third scale-degree, “mi”).

When this melodic phrase returns for lines 7–8, it leaves us hanging and justifies the singing of a refrain that is purely the invention of the composer, William Doane.

Tell me the old, old story,

tell me the old, old story,

tell me the old, old story

of Jesus and his love.

It’s beautifully crafted. The notes of the first line are those to which we sang these words before, at the beginning of the hymn. But now the melody stops short after just seven notes; rather than proceeding to unfold a sustained train of thought (as it did before), the melody here interrupts itself to repeat the first seven notes at a higher pitch level, soaring past what till now had been the tune’s highest pitch and even hitting a high E in the third line of the refrain. Although it may be the most repetitive text studied on this web site, it’s rhetorically effective, not repetitious: just as little children (and the humble) like to hear the same stories over and over again, so, too, they can be importunate in asking for it. Besides, here we ask not just for any old story but for “Jesus and his love.” The last line of the refrain reworks the inconclusive music used earlier for these words (back in measures 7–8) into something solid, something whole.

NOTE

[1] J. R. Watson, The English Hymn: A Critical and Historical Study (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 493.