The Day of Resurrection!

John of Damascus, 8th century; translated by John Mason Neale, 1862

Addressed to one another

| The day of resurrection! | |

| Earth, tell it out abroad; | |

| the Passover of gladness, | 1 Cor. 5:7; 1 Pet. 1:18–19 |

| the Passover of God. | Rom. 3:25 |

| From death to life eternal, | John 5:24 |

| from this world to the sky, | Eph. 2:6 |

| our Christ hath brought us over | Josh. 4:19 (cf. Ex. 12:3) |

| with hymns of victory. | Ps. 105:43 |

| Our hearts be pure from evil, | Matt. 5:8; Heb. 12:14 |

| that we may see aright | Luke 24:16; John 20:14; 21:4 |

| the Lord in rays eternal | |

| of resurrection light; | Matt. 28:3; Phil. 3:21 |

| and listening to his accents, | |

| may hear, so calm and plain, | |

| his own “All hail!” and hearing, | Matt. 28:9 |

| may raise the victor strain. | |

| Now let the heav’ns be joyful, | Is. 49:13 |

| let earth her song begin; | |

| let the round world keep triumph, | Rom. 8:22 |

| and all that is therein; | |

| invisible and visible, | |

| their notes let all things blend, | |

| for Christ the Lord hath risen, | |

| our joy that hath no end. | Is. 35:10; Heb. 7:16, 24–25 |

Every atom of general revelation and every verse of Scripture makes most sense when read in the light of the apostolic testimony to Christ’s resurrection. Without it, as in any modern Christianity that disregards God’s Word, we lose our ability to see how things—our nature, our circumstances, our destiny—fit. Hope fades. Yet in every town one finds pastors who refer to his resurrection only in equivocal terms. They speak glowingly of the eschatological symbol, the Easter visions, and the “appearances” of Jesus (always with a generous use of distancing quotation marks), but they and their teachers set faith in opposition to fact: “The resurrection of Jesus from the dead by God does not speak the ‘language of facts,’” wrote Jürgen Moltmann, “but only the language of faith and hope, that is, the ‘language of promise’” (The Crucified God [Fortress Press, 1993], 173). But what kind of Christianity does not treat God’s Word as fact?—indeed, as the ultimate fact, which makes it possible for there even to be facts? Meanwhile, countless ordinary Christians languish, distracted by their own fears, disappointments, and confusions, and forget that “death shall be no more” (Rev. 21:4). Their faith seems futile, their sins a burden (1 Cor. 15:17).

By contrast, the singers of this hymn desire resurrection knowledge. They wish to see and hear (stanza 2, lines 2 and 6). They want everything, each in its own way, to tell abroad (stanza 1, line 2) that Christ was raised in accordance with the Scriptures—on an actual day (first line), with consequences for every other day, as long as there are days, and beyond, to a joy that has no end (last line). The hymn is especially clear about the two things that have to happen if we are to see the resurrection aright (stanza 2, line 2). First, our hearts must be cleansed of the sin that clouds our vision (stanza 2, line 1); all too often we don’t see the risen Lord accurately because, frankly, we don’t want to. Second, we must listen to him (stanza 2, line 5); his Spirit must illumine our hearts so that we understand and heed his word, that is, the Bible.

“Passover” in the first stanza has a double meaning. At first we think, correctly, of deliverance from the tenth plague: the Lord, seeing the blood of the Lamb, passes over Israel so we escape destruction. But this redemption results in a passage from Egypt over to Canaan, from death to life, from this world to heaven.

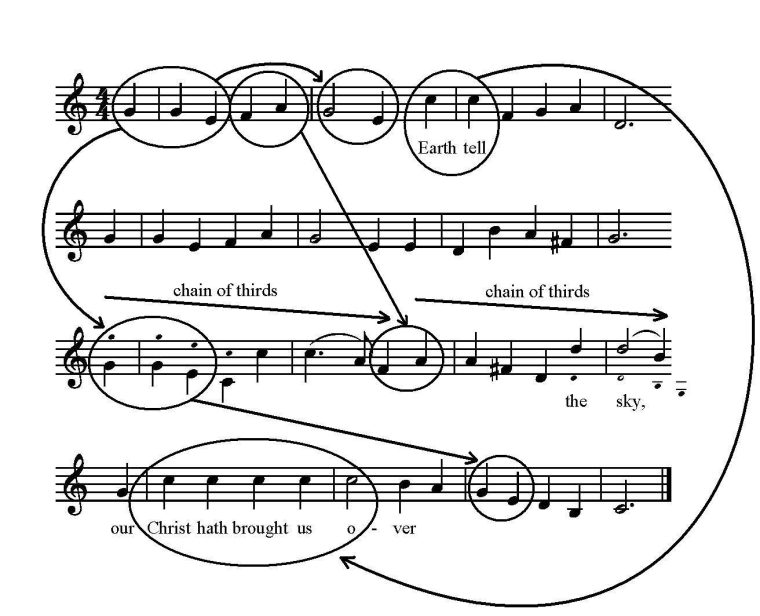

LANCASHIRE’s assertive dominant harmony at the close of lines 4 and 6 of the stanza underscores the urgency of the words. It seems the tonal equivalent to the eight exclamation points that John Mason Neale included in the first printing of the poem. The small melodic leap of only two steps from F to A in the middle of line 3 (measure 5) expands to five steps in line 4 (measure 7) and then to an octave, and high C, in line 5 (“life eternal” in measure 9). This octave-leap reappears a step higher in line 6 to reach high D (“to the sky” in measure 11). All four voices are quite active in lines 5–6. The soprano’s descending arpeggios derive from the headmotif G–E (see diagram), replicating that descent over and over again on different pitches in what music theorists might call a “chain of thirds” (a “third” being the technical term for the distance between two pitches two steps apart).

The climax arrives in line 7 when the repeated high C of line 2 (“Earth tell”) expands to a fivefold repetition for the climactic words located here in all three stanzas of the poem. This, we believe, makes LANCASHIRE ideal for “The Day of Resurrection!” No other tune used for it has nearly as strong a seventh line. LANCASHIRE does have another text commonly associated with it: “Lead On, O King Eternal.” But we question whether its pacifist postmillennialism, however much it tries to do justice to verses like Matthew 26:52 and 2 Corinthians 10:4, really agrees with Scripture as a whole (Revelation 19, for instance).