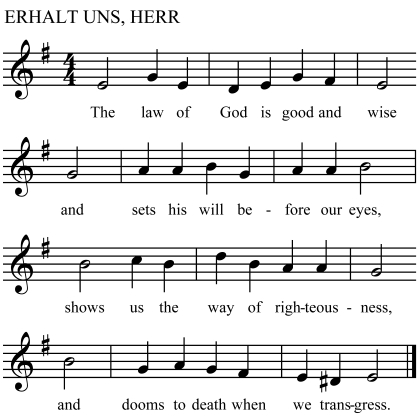

The Law of God is Good and Wise

Matthias Loy, 1863

Addressed to one another

| The law of God is good and wise | Rom. 7:12; Ps. 19:7 |

| and sets his will before our eyes, | Rom. 2:18; Deut. 6:8 |

| shows us the way of righteousness, | Deut. 6:25 |

| and dooms to death when we transgress. | Rom. 6:23 |

| Its light of holiness imparts | Ex. 34:29 |

| the knowledge of our sinful hearts, | Rom. 3:20b; 7:7 |

| that we may see our lost estate | Is. 6:3–5 |

| and seek deliv’rance ere too late. | Ps. 83:16; Is. 55:6 |

| To those who help in Christ have found | |

| and would in works of love abound | John 14:21; 1 John 5:2–3; 2 John 1:6 |

| it shows what deeds are his delight | Prov. 11:1 |

| and should be done as good and right. | Eph. 5:9–10 |

| When men the offered help disdain | 1 Tim. 1:9–10 |

| and willfully in sin remain, | 2 Thess. 2:12 |

| its terror in their ear resounds | Ex. 20:19 |

| and keeps their wickedness in bounds. | |

| The law is good; but since the fall | 1 Tim. 1:8 |

| its holiness condemns us all; | 2 Cor. 3:9 |

| it dooms us for our sin to die | Rom. 7:9–10 |

| and has no pow’r to justify. | Rom. 3:20a; Gal. 2:16; 3:11 |

| To Jesus we for refuge flee, | Heb. 6:18 |

| who from the curse has set us free, | Rom. 8:2; Gal. 3:13 |

| and humbly worship at his throne, | |

| saved by his grace through faith alone. | Rom. 4:16; Eph. 2:8 |

This hymn is an admirably complete summary of how the moral law of God relates to the gospel of Jesus Christ. It explains what the law does (st. 1), how it is to be used (st. 2–4), and why its function as a means of grace is only complete when combined with the gospel (st. 5–6). It does all this at an easy pace, with perfectly rhymed couplets, standard word order, and simple language. It’s obviously a very useful hymn of exhortation. If conservative Lutherans and conservative Presbyterians, in whose hymnals it appears, underutilize it in favor of hymns of praise and personal testimony, this may suggest a measure of how forgotten is the command to teach one another in song. Because the use of song for purely didactic purposes is uncommon elsewhere in life, we are prone to overlook a valuable tool like this hymn, which versifies one of the most important aspects of biblical thought.

According to stanza 2, by uncovering sin the law rouses men to a sense of their peril and need for a Savior. This is what the Formula of Concord (1577) called the second, and what John Calvin called the first, use of the law. The initial image of “light” works well with the third line’s verb, “may see,” and connects alliteratively with the most powerful words of the stanza: “lost” and “late.”

Anyone who, convicted by this so-called pedagogical use of the law, flees to the mercy of God in Christ and rests in him will find thereafter another use for the law, which both the Lutherans and the Reformed count as the third. It shows believers what to do with their longings to obey. Illuminated by Christ’s Spirit, they find in the law a way to “abound” in works of love and deeds in which God “delights,” as stanza 3 puts it.

But, for those who resist the pedagogical use of the law, there is yet another use, described in stanza 4. It’s enumerated as the first use in the Formula of Concord and as the second use in Calvin’s Institutes. As a kind of common grace, the law’s “terror” resounds in their ears to restrain their sin for the good of the human community.

The uses described back in stanzas 2–3, by contrast, serve God’s special grace, the promises of justification and sanctification that are ours in Jesus Christ. Stanzas 5–6 make this clear. Law and gospel, as distinct as they are, cannot be separated. How fitting, then, that a hymn on a topic that was so important to the Reformation churches—to their reading of Scripture, their preaching, and their Christian living—ends with two of their solas: “saved by grace through faith alone.”

How fitting, too, that it be sung (as it always is) to a melody likely composed by Martin Luther himself! A sturdy thing, its range sticks to an octave, and its rhythm remains the same from phrase to phrase. These explore the melodic possibilities of the interval known as a third, which is the difference in pitch between a note on a staff-line and a note on an adjacent line, as in the first two notes here. The melody moves stepwise between, and embellishes with neighboring notes, the members of the tonic chord: the pitches E, G, and B. The first line of the stanza (that is, the first two and half measures of the melody) ascends to G and returns to E. The second line of the stanza traverses the space between G and B. The third line proceeds from there to a high D, before outlining stacked thirds in its decent from D to B to G. The fourth line does nearly the same, only lower: B to G to E.

Thus it’s not hard to demonstrate the tune’s coherence. It posits a musical idea and develops it in a way that is formally rounded and tonally vivid. Especially successful is the inflection in line 3 to what music theorists call the relative major mode and return, in line 4, to the home key. The result is unusually colorful for a tune so simple. It proves itself as congregationally useful as the words do.

Congregations already inclined to an unnatural focus on the oppressive nature of the law apart from Christ may misunderstand the tune’s minor modality as somber or even gloomy. Taken at a fast enough tempo, however, the tune can sing instead of wail and thus avoid this misunderstanding.