The Sands of Time Are Sinking

The Last Words of Samuel Rutherford

Anne R. Cousin, 1857

Addressed to one another and, perhaps especially, ourselves

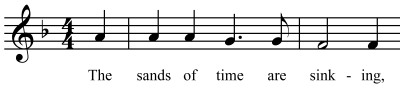

| The sands of time are sinking, | Rom. 13:11; 1 Cor. 7:29; 2 Cor. 4:17a; 1 Pet. 1:6 |

| the dawn of heaven breaks, | |

| the summer morn I’ve sighed for, | |

| the fair sweet morn awakes; | 2 Pet. 1:19 |

| dark, dark hath been the midnight, | |

| but dayspring is at hand, | Rom. 13:12 |

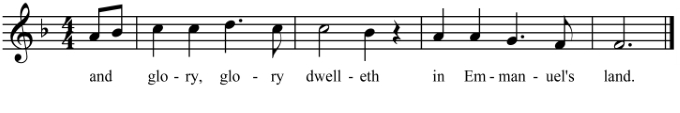

| and glory, glory dwelleth | Ps. 85:9; John 11:40; Rev. 21:11, 23 |

| in Emmanuel’s land. | |

| The King there in his beauty | Is. 33:17 |

| without a veil is seen; | 2 Cor. 3:16 |

| it were a well-spent journey | |

| though sev’n deaths lay between: | Rom. 8:18 |

| the Lamb with his fair army | Rev. 14:4; 19:14 |

| doth on Mount Zion stand, | |

| and glory, glory dwelleth | |

| in Emmanuel’s land. | |

| Oh, Christ, he is the fountain, | Jer. 2:13; John 4:10 |

| the deep sweet well of love! | |

| The streams on earth I’ve tasted | |

| more deep I’ll drink above: | Rev. 22:1 |

| there to an ocean fullness | Ezek. 47:5; Zech. 14:8 |

| his mercy doth expand, | |

| and glory, glory dwelleth | |

| in Emmanuel’s land. | |

| The bride eyes not her garment, | Rev. 19:8 |

| but her dear bridegroom’s face; | Song 5:12–13; Rev. 22:4 |

| I will not gaze at glory, | Prov. 25:27 |

| but on my King of grace; | |

| not at the crown he gifteth, | Rev. 4:10 |

| but on his piercèd hand: | John 20:20 |

| the Lamb is all the glory | |

| of Emmanuel’s land. |

Samuel Rutherford (c. 1600–1661) was a village pastor, a writer, and one of the Scottish commissioners to the Westminster Assembly. It is mostly for his personal correspondence, however, that he is remembered today. Recipients of his letters were so encouraged by what he wrote to them that they often made copies to share with friends. After his death these were collected and published as a book—arguably the most beloved devotional text in Scottish history.

At the very end of his life someone asked him, “What think ye now of Christ?” to which he replied, “I shall live and adore him. Glory, glory to my Creator and to my Redeemer forever! Glory shines in Emmanuel’s land.” Almost two centuries later the poet of the hymn above derived its refrain from these words and filled out the rest with ideas and images from Rutherford’s letters. A recurring theme in them is love for heaven. Rutherford liked to remind his correspondents of the biblical vision of eternal life, for he believed God revealed it to strengthen believers in the trials of this life. He believed that, with a theology of heaven, we can meet suffering with faith and courage.

Ye shall find it your only happiness, under whatever thing disturbeth and crosseth the peace of your mind, in this life, to love nothing for itself, but only God for Himself. It is the crooked love of some harlots, that they love bracelets, earrings, and rings better than the lover that sendeth them. God will not be so loved; for that were to behave as harlots, and not as the chaste spouse, to abate from our love when these things are pulled away. Our love to Him should begin on earth, as it shall be in heaven; for the bride taketh not, by a thousand degrees, so much delight in her wedding garment as she doth in her bridegroom; so we, in the life to come, howbeit clothed with glory as with a robe, shall not be so much affected with the glory that goeth about us, as with the bridegroom’s joyful face and presence. Madam, if ye can win to this here, the field is won; and your mind, for anything ye want, or for anything your Lord can take from you, shall soon be calmed and quieted. (Rutherford to Lady Kenmure, 14 January 1632)

Oh how sweet is it that the company of the first-born should be divided into two great bodies of an army, and some in their country, and some in the way to their country! If it were no more than once to see the face of the Prince of this good land, and to be feasted for eternity with the fatness, sweetness, dainties of the rays and beams of matchless glory, and incomparable fountain-love, it were a well-spent journey to creep hands and feet through seven deaths and seven hells, to enjoy Him up at the well-head. Only let us not weary: the miles to that land are fewer and shorter than when we first believed. (Rutherford to Lady Kenmure, 1 January 1646)

Loving heaven, it turns out, is just a species of loving Christ. An assurance that his saving work shall be consummated in heaven, where we’ll enjoy perfect fellowship with God forever, puts current troubles in perspective.

The intentionally vague opening of “The Sands of Time Are Sinking” builds expectation by alluding to, but not revealing, its topic. It is not apparent what the “dawn of heaven” is. A metaphor? Or, literally, the rising of the sun into the sky? (As some congregations sing, “Morning has broken like the first morning, blackbird has spoken like the first bird.”) The falling rhythms of the words “sink-ing” and “sighed for” match their meaning, as do, by contrast, the accented line-endings “breaks” and “a-wakes.” But what is breaking? What is awaking? Just as we wait in this life for faith to be made sight, so, too, this stanza clarifies its subject matter only at the end. We’re singing about the glory of Emmanuel’s land, the land of God-with-Us. The poet intensifies the revelation rhythmically: after seven lines of seven syllables and six syllables in alternation, the last line has only five. We’ve arrived.

Then, in subsequent stanzas, we expound on this idea that longing for heaven is really longing for Christ. In stanza 2 we sing of seeing his beauty. In stanza 3, of drinking from his love. In stanza 4 we forget ourselves entirely, and the refrain changes: “the Lamb is all the glory of Emmanuel’s land.” When we sing that we “will not gaze at glory, but on my King of grace,” we should not be surprised. All joys in heaven and earth are really ways of fulfilling the greatest commandment, to love the Lord your God—most clearly seen in our love for Christ and his saving work.

The tune was adapted from a French source by an English editor in 1866 especially for this text. The melody paints the opening image with a gradual descent to “do.”

At the other end of the stanza, the melody reaches its highest note on “glory” and underscores with a pregnant pause the sense that the last five syllables are a revelation.