Who Is on the Lord’s Side?

Frances R. Havergal, 1877

Addressed to one another and to God

| Who is on the Lord’s side? | Ex. 32:26 |

| Who will serve the King? | |

| Who will be his helpers, | Judg. 5:23; 1 Cor. 3:5 |

| other lives to bring? | Matt. 12:30 |

| Who will leave the world’s side? | 2 Cor. 6:17; 1 John 2:15 |

| Who will face the foe? | Ps. 44:5; 60:12 |

| Who is on the Lord’s side? | |

| Who for him will go? | Is. 6:8 |

| Response. By thy call of mercy, | 2 Tim. 1:9 |

| by thy grace divine, | |

| we are on the Lord’s side; | |

| Savior, we are thine. | 1 Chr. 12:18; 1 Cor. 6:19b |

| Not for weight of glory, | Ps. 115:1 |

| not for crown and palm, | Rev. 4:10 |

| enter we the army, | |

| raise the warrior psalm; | |

| but for Love that claimeth | 1 John 4:8–11 |

| lives for whom he died: | |

| he whom Jesus nameth | Is. 43:1; John 15:16 |

| must be on his side. | |

| Response. By thy love constraining, | 2 Cor. 5:14 |

| by thy grace divine, | |

| we are on the Lord’s side; | |

| Savior, we are thine. | |

| Jesus, thou hast bought us, | 1 Cor. 7:23 |

| not with gold or gem, | 1 Pet. 1:18 |

| but with thine own lifeblood, | 1 Pet. 1:19 |

| for thy diadem: | Is. 62:3 |

| with thy blessing filling | |

| each who comes to thee, | |

| thou hast made us willing, | Phil. 2:13 |

| thou hast made us free. | John 8:36; 1 Cor. 7:22 |

| Response. By thy grand redemption, | |

| by thy grace divine, | |

| we are on the Lord’s side; | |

| Savior, we are thine. | |

| Fierce may be the conflict, | Rom. 7:23 |

| strong may be the foe, | Ps. 18:17 |

| but the King’s own army | 1 Sam. 17:26 |

| none can overthrow: | |

| round his standard ranging, | Is. 11:12 |

| vict’ry is secure; | |

| for his truth unchanging | Ps. 43:3; 119:160 |

| makes the triumph sure. | |

| Response. Joyfully enlisting | 2 Tim. 2:4 |

| by thy grace divine, | |

| we are on the Lord’s side; | |

| Savior, we are thine. |

One day, prior to the conquest of Jericho, Joshua spotted a man standing before him with a drawn sword. Approaching the stranger, he asked something like “Whose side are you on? Ours? Or theirs?” The reply dramatically shifts our frame of reference in a single word of negation:

“No; but I am the commander of the army of the LORD. Now I have come.” And Joshua fell on his face to the earth and worshiped and said to him, “What does my lord say to his servant?” And the commander of the LORD’s army said to Joshua, “Take off your sandals from your feet, for the place where you are standing is holy.” And Joshua did so. (Josh. 5:14-15)

Joshua’s initial question assumed a false alternative, from a man-centered point of view. It’s one thing to exclaim with Paul, “If God is for us, who can be against us?” It’s another thing entirely to conceive of God as being “on our side”—the ancient watchword of warmongers and xenophobes—as if he were an ally to be tactically mobilized in some human cause. Rather, the battle is his, and the question to be asked is: whose side are we on?

Among Frances Ridley Havergal’s many attractive books were four collections of daily devotions on what she called the “royal utterances of our King,” to which in 1877 she added a fifth volume, Loyal Responses, to model a faithful subject’s answer to these utterances. In contrast to their prose predecessors, the thirty-one Loyal Responses are all poems, the first of which is “Take My Life and Let It Be,” and the fifth, the poem printed above. It treats the topic of loyalty, taken from the book’s title. No one can serve two masters (Matt. 6:24). All must choose a side.

The call to service (or is it a call to arms?) is insistent, with interrogative whos launching seven of the first eight lines. It’s not to be dodged, because love constrains us (stanza 2), because he who is Love can lay claim to us, and because the one whom Jesus nameth “must” be on his side. And yet, for all that constraint, the call is ultimately liberating, too (stanza 3). We are “willing.” We are “free.” We are redeemed—redeemed for victorious ends (stanza 4). Hence the joy in our enlistment.

Each stanza presents and develops one idea coherently. The four stanzas collectively unfold a compelling train of thought, which can be summarized by reading the ninth line of each. In the “response” refrain that closes every stanza, this is the one line that changes: from “call” in stanza 1, to “constraint” in stanza 2, to “redemption” in stanza 3, to “joy” in stanza 4.

The sounds of the words do their part, too. Consider just the first stanza. The alliterative third line (who–his–helpers) grabs our attention before the consonants in “lives” (line 4) recall those in “will serve” (the same foot, two lines earlier) and flow into the first rhyme (king–bring). The alliteration in the second quatrain comes earlier, in the second line of the quatrain (face the foe) instead of the third. The job now of this third line (the seventh of the stanza) is no longer to repeat merely the initial or ending sound of a syllable but to repeat an entire line: the first, making as clear as possible the parallel between Jehovah’s question to Isaiah (line 8) and Moses’s to the Israelites (lines 1 and 7).

There is a crescendo of poetic devices that climaxes with the refrain. Indeed, we find this in the other stanzas as well. In stanzas 2–4, a single rhyme in the first quatrain intensifies to interlocking rhymes in the second quatrain. That is, whereas lines 1 and 3 do not rhyme with each other, lines 5 and 7 do. This increase in sonic organization culminates with repetition across stanzas via the refrain.

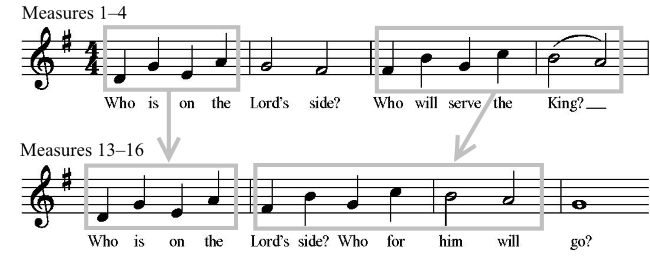

A successful tune must reinforce the way Havergal builds to her climactic, thematic line 11, “we are on the Lord’s side.” Thankfully, both tunes in use do. ARMAGEDDON was penned by the same English composer who wrote LAUDA ANIMA (Praise, My Soul, the King of Heaven). ARMAGEDDON maintains energy over the span of the long stanza by means of a lengthy change of key—lengthy, that is, for a hymn tune. After the melody rests repeatedly on the pitch F during the first four lines of the stanza, the harmony actually transforms it into the tonal center (“do”) in measure 8. To steer things back to the original key, the bass settles on an electrifying pedal point for lines 5–6 (which contrasts dramatically with the rallying-cry arpeggio with which the bass opened back in m. 1). The return to the original key in measure 13 coincides in stanza 1 with a return to the opening question: “Who is on the Lord’s side?” ARMAGEDDON then reinforces the climactic eleventh line through changes of texture. The unison bugle calls of “by thy call of mercy, by thy grace divine” make the return to four-part harmony at line 11 a bigger sound by comparison.

RACHIE is Welsh, like CWM RHONDDA (Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah), BLAENWERN (For Your Gift of God the Spirit), and BRYN CALFARIA (Come, Ye Sinners, Poor and Wretched). The music of ARMAGEDDON underscores tonally the textual repetition in stanza 1 (between lines 1 and 7) by returning to the home key. In RACHIE, the melody itself returns to its orginal phrase, but compressed to sweep us on to the refrain.

Like ARMAGEDDON, RACHIE reinforces the climactic eleventh line through changes of texture. The equal-voiced polyphony of “by thy call of mercy, by thy grace divine” solidifies into emphatic chords for line 11 as the melody lifts to high E: a height reached by only 8% of the tunes on this website.

We recommend both ARMAGEDDON and RACHIE. Their muscular leaps, ambitious ranges, and taxing lengths require congregants to exert themselves as they raise the warrior psalm. At the same time, there’s enough musical substance here to counter any lingering superficial jingoism we may harbor about “our side” and “their side.” With Joshua, we stand on holy ground.

ARMAGEDDON

RACHIE